Rowland S Howard had plans for old age. “When I’m 60, there will be feedback coming out of the house and little kids will cross the road when they walk past,” he said. Sadly, Howard’s plan for a screeching house of horrors didn’t come to fruition – he died of liver cancer in 2009, aged 50.

He was the incendiary guitarist in Nick Cave’s pre-Bad Seeds outfit, the Birthday Party, spewing torrents of ear-destroying feedback that ricocheted between swampy blues and industrial terror. He was frequently imitated but never matched. “Our song Don’t Cramp My Style was pure Birthday Party tribute,” says My Bloody Valentine’s Kevin Shields. “People sue for less nowadays – it was me doing my best Rowland impersonation. His use of feedback was a huge inspiration. The sound was explosive and silky like channelled electricity.”

However, as radical as Howard was, you’re not going to find him among Rolling Stone’s 100 greatest guitarists. After the Birthday Party he didn’t share the same career trajectory as the Bad Seeds. “Like the poet Shelley, it’s shameful these people died poor and relatively anonymous,” says Lindsay Gravina, who produced Howard’s two solo albums, Teenage Snuff Film and Pop Crimes, which are being reissued by Mute, following a recent tribute concert at the Royal Festival Hall in London. “But people who ‘get’ him do so the way people get Lou Reed or Bob Dylan.”

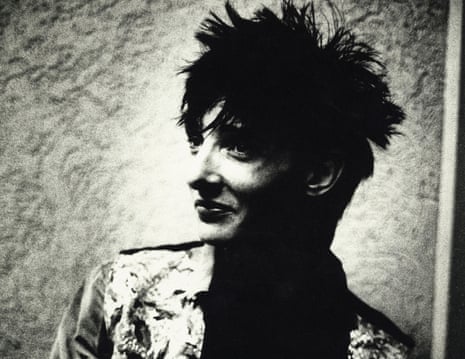

Harry Howard, Rowland’s younger brother, recalls him being singular from a young age. “At 10 he had long hair, wore all black and carried a walking stick.” Such was the strange allure of pre-teen Howard that girls would follow him in the street. “He was an odd-looking person,” says Mick Harvey of the Birthday Party, Bad Seeds and Crime & the City Solution. “He was something of a dilettante – a bit pretentious.” However, once Harvey heard Howard’s teenage band, the Young Charlatans, he realised there was substance behind the lofty demeanour. They poached him for their new wave band, the Boys Next Door, fronted by a teenage Nick Cave. Howard brought the song Shivers, an ironic ballad about teenage-crush hysteria that he wrote when he was 16. It remains the band’s greatest moment.

By 1980, the band had become the Birthday Party and together moved to London. They arrived bitterly disappointed. “Rowland took London personally,” Cave said in the 2011 documentary, Autoluminescent. “Like someone had built it to make him unhappy.” The band felt disconnected and were surrounded by bands they felt were banal and insipid. “We went from being big fish in a small pond to frogspawn in an ocean,” Howard said. Howard and Cave also arrived with heroin habits that exacerbated their bleak situation, one that resulted in Howard suffering from malnutrition while living in a squat.

However, the animosity the band felt towards their new home mutated into a vituperative musical intensity, and they were soon a hot ticket. Cave was feral, all guttural screams ringing out above Tracey Pew’s barbaric bass, Harvey’s bone-snapping drum beats and Howard’s feedback orchestra. “When it all came together, and the chemicals were at the right balance, the shows were absolutely unbelievable,” says Harvey. “No video footage,” Gravina says, “comes remotely close to capturing the sheer terror and excitement of the Birthday Party.”

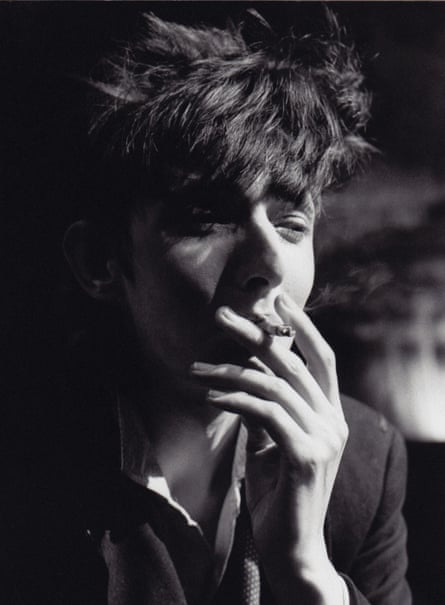

On stage, Howard cut an idiosyncratic figure. From his elfish and vampiric face dangled a perma-glued cigarette as he scuttered around, hammering the tremolo arm of his Fender Jaguar. Cave was aware of Howard’s unique touch – “As soon as he played two notes you knew it was him” – but the Birthday Party was struggling. “It was so intense and fiery,” says Harvey. “There wasn’t any communication going on, plus people were on drugs, which made things worse.”

Howard had been a co-writer in the band, musically and lyrically, but he and Cave began to drift apart. “Nick didn’t want to write with him or sing his lyrics any longer, and Rowland felt ostracised,” says Harvey. “It was a bit of a death knell for the band.”

As tensions peaked, Einstürzende Neubauten’s Blixa Bargeld was brought in to play some guitar on the band’s final recording sessions. “There was a lot of ill feeling about Blixa being brought in,” says Harvey. “Rowland felt rejected.” Cave, Harvey and Bargeld formed the Bad Seeds without Howard. “He was upset,” says his brother. “It seemed like everyone carried on without him. He felt the rug had been pulled out from under him. He was at a loss for a while, depressed.”

Despite being invited for a couple of guest appearances on Bad Seeds records, Harvey says wounds never truly healed with Cave. “He had misgivings and resentments about Nick up until the end.”

After spending 1985-86 in Crime & the City Solution – a Gun Club-like fusion of blues, punk and gloomy rock – Howard formed These Immortal Souls, ostensibly a solo project that merged melancholic melody with jagged post-punk. However, as the 80s became the 90s, thrust for Howard was inverse to his ex-bandmates. “Rowland was dismissed by a lot of people after the Birthday Party,” his brother and These Immortal Souls bandmate says. “People thought he was old news and washed up. When we finally released our second album, in 1992, it felt like everyone was totally bored by us – Rowland had become unfashionable. Nick Cave was going from strength to strength, but as he went up Rowland seemed to slide down the other side.”

For some, though, Howard remained an unwavering figure. “The first thing I said to him when I met him was, ‘I want to fuck you’,” recalls Bobby Gillespie with a hearty laugh. “He was a guitar hero during a time when there were no guitar heroes.” The singer, poet and no-wave figure Lydia Lunch collaborated with Howard frequently. “He was fragile and I always felt he was not for long for this world,” she says. “That created an urgency in wanting to work with him.” The pair struck up a relationship in the early 80s when Howard accompanied her spoken-word performances with improvised guitar. “Most people want to make as much noise as possible but he understood the economy of sound,” she says.

Those who knew him described Howard as obdurate, earnest, sensitive and hopelessly romantic. Although another consistency in his life was heroin. “It had quite an influence on his creativity,” says his brother. “Whenever he came off heroin he’d get this massive nerve-jangling awakening. A lot of the songs people think are about drugs are actually about stopping taking drugs.” But things never got too desperate, he says. “He was quite stoic. If he couldn’t get drugs on tour, then he would just suffer quietly. He always maintained this sense of being a gentleman junkie. It never got debauched and he wasn’t stealing. He had a stable life – it was quite a domestic addiction.”

It was 1999 before Howard released another record, Teenage Snuff Film, an album that deftly marries 60s girl-group pop, shimmering cowboy twang guitar and caustically romantic lyrics delivered by Howard’s rich and heroin-free voice. “He said it would be awful if the Birthday Party was the best thing he’d ever done,” says his brother. “But he really believed in that album and that it was the best thing he’d ever done.” It was initially met with indifference. “He was crestfallen,” says Gravina. “It’s been accorded cult status as a much loved album now, but back then nobody wanted to know.”

Over time a new generation was growing wise to Howard’s non-Birthday Party output. “I knew every word to Teenage Snuff Film,” says Jonnine Standish of Aussie band HTRK, who Howard went on to produce. “It was a big influence and we were taken with his mystical reputation as being a bit of a bat.” Jehnny Beth of Savages also regarded him as a revelation. “He was a huge inspiration for early Savages,” she says. “I’d never heard someone play guitar that way. It was like a sound I’d been waiting all my life to hear – and lyrically he’s as powerful as Rimbaud.”

When Pop Crimes was released in 2009, momentum around Howard had intensified. “There was a groundswell of interest and it jolted him into action,” Harvey recalls, as does his brother. “He was so ready for it. He was really sick but he thought he was going to get out of the hospital.” However, it was all too late. A previously unrepentant drug user, Howard expressed deep regret in his final moments. “I’ve lost so much of my life,” he said. “It’s been wasted – thrown away.”

At the time, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs had invited Howard to support them on an Australian tour, but he was too ill. “We were driving in Tasmania listening to the radio when they played a Rowland Howard song,” says their guitarist Nick Zinner. “And then they played another. We all knew what had happened, and we just wept the rest of the journey.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion