WLW, esteemed history enthusiast, pseudohistory debunker, haniwa purveyor, biggest Ninshubur fan not counting Rim-Sin of Larsa

Catching Elephant is a theme by Andy Taylor

Who is Baal, anyway?

As I mentioned in my previous article, the instigator of the recent attacks on museums in Berlin believes some of the artifacts held in them to be part of a nefarious, bloodthirsty cult, prominent on the “global satanism scene” and devoted to “Baal (Satan),” as he put it himself according to articles covering this incident. In the following article I’ll discuss the origin of this esoteric claim, as well as the actual nature of Baal, myths associated with him, other similar deities and their role in the ancient Middle East (and beyond).

I’ll start with the

matters I am not particularly enthusiastic about: Baal is the star of

many conspiracy theories, mostly these which arise in christian

fundamentalist circles, and which cast him as the deity venerated by

nefarious groups, ranging from insufficiently conservative political

parties and ethnic minorities to vampiric aliens, blamed for all of

the world’s evils.

He owes this status to being one of the

most frequently mentioned “false gods” or “idols” in the

Bible. In fringe pseudohistory context it’s basically a given that

Baal is equated with the nebulous figure of Moloch, the child

sacrifice boogeyman. They are not actually analogous, though - Baal

is brought up in relation to idol worship, depicted as powerless, and

generally associated with people from coastal cities like Sidon and

Tyre – the groups Greeks collectively called „Phoenicians.”

Moloch meanwhile is associated with the Ammonites, whose

kingdom lied further inland – it is possible that he is therefore a

biblical corruption of the Ammonite god Milkom. Some researchers

propose instead that “Moloch” was a type of sacrifice involving

the burning of victims in honor of a deity – this theory matches

both the accounts of biblical Moloch, as well as some Greek and

especially Roman accounts meant to prove the debased, barbaric nature

of Phoenicians, especially these from Carthage.

In later

writing, all of the idols and false gods mentioned in the Bible were

equated with the devil - in reality their inclusion in biblical text

likely reflects struggle between various faiths and their cult

centers in ancient Canaan, and later increasingly more fragmentary

memories of it. In Christian demonology and in occultism, in addition

to their names being considered synonyms of the devil, new demonic

identities were assigned to them, which is where the popculture idea

of Beelzebub, Bael and other similarly named figures has its origin.

As almost every type of pseudohistory eventually connects to

blood libel (or an equivalent of it), the exaggerated assumptions

about biblical Moloch inspired Gilbert K. Chesteron to propose that

blood libel was based on real events, specifically on possible

outbreaks of “idolatry” in Jewish communities leading to bloody

sacrifices. Needless to say, this is an outlandish, baseless claim

rooted in prejudice.

The scarce textual sources left behind

by the Phoenicians themselves do not discuss any rites which match

biblical and roman claims particularly commonly – occasional

mentions paint an image similar to the sacrifice of Iphigenia in

Greek myth, which would imply that human sacrifice was either the

domain of myth, or a rarely performed act which only occurred as an

irrational response in times of great peril. Romans claimed the

epicenter of such practices was Carthage, their early rival to the

title of the preeminent power of the Mediterranean, and its recipient

was its tutelary god, Baal Hammon – a figure not directly relate to

the biblical Baal(s), who I will discuss later, but for centuries

commonly assumed to be one and the same as him due to the lack of

primary sources.

Excavations from Carthage do show the

existence of funerary sites with a high concentration of child

burials, but it’s a matter of heated scholarly debate if they

represent a proof of Roman propaganda being rooted in truth, or if

it’s simply the result of the well known fact that infant mortality

prior to modern times was widespread. The debate is ongoing and I do not

follow it closely.

There is however precisely zero evidence of

human sacrifice being performed in Ugarit, the most significant site

associated with the most famous, and arguably original, Baal. The

extensive cult literature recovered from its ruins discusses the

sacrifice of cattle, sheep, rams, birds (but only uncommonly),

donkeys (only for a specific reconciliation rite), oil, wine, and

precious stones and metals - but not humans (researchers also often

point out that dogs and pigs were never offered to gods too, which is

a pretty clear proof that some taboos present in abrahamic faiths

predate them).

The Ugaritic texts do mention that sacrificial

meat was at least sometimes shared by the devotees (in the case of

sacrifices which did not involve a pyre, obviously – which

essentially means such sacrifices were feasts or holiday meals

ritually shared with the deity), which I assume where the false idea

that both Phoenicians of classical antiquity and their bronze age

Canaanite forerunners were cannibals might come from.

This

specific claim seems to be currently spreading as “trivia”

online, alongside a false etymology of the word cannibal (a term only

attested since the beginning of Spanish colonization of the

Americas). It should be noted that even the researchers who do

believe that human sacrifice might have sometimes occurred in

Carthage do not suggest that it was followed by cannibal feasts, and

even in Roman propaganda texts from the Punic wars period no such

claims show up, despite their obvious bias and need to demonize the

recently vanquished rival nascent power.

In art of ancient Levant,

worshipers are sometimes depicted as tiny compared to gods – many

“scandalous” conspiracy posts claim as a result that the

minuscule figures raising their hands on ancient artifacts represent

infants sacrifices to the gods depicted. However, accompanying

inscriptions identify them as kings or priests – this is the case,

for example, with the famous Baal stele from Ugarit, depicting a king

praying to the tutelary god of the city.

With the unpleasant

matters out of the way, it’s time to finally ask - who is Baal?

Baal refers both to a specific figure, and to the general

concept of a head god of a city’s pantheon in certain parts of the

Levant and Mesopotamia. “Baal” simply means “lord” and can be

found in both titles and names of not only gods, but also royals –

including some biblical examples.

As I said, the Baal most famous today is Baal Hadad of Ugarit, a city in present day Syria which was among the victims of bronze age collapse. This Baal was derived from an earlier god, Adad, who seemingly first became a major figure near present day Aleppo, emerging as the head of the local variation of Syro-Hurro-Mesopotamian pantheon. Eventually, the title of Baal started to be regarded as his true name, with Hadad relegated to the rank of a title. His other titles include “Rider of Clouds” and “Aliyan” (“Victorious”). His cult survived the destruction of Ugarit, and flourished well into Ptolemaic times.

In Ugarit, he served not

only as a god of rain and thunder, but also agriculture and

fertility, and, as expected from the lead god, a source of royal

power. He was depicted as an impulsive and boastful figure in myths, but was

also a firm ally of humans, subduing monsters, the forces of nature,

and even promising to protect his followers from wrath of other gods

in myths. His symbolic animal was the bull, and he was usually

depicted in horned headwear. The associations between bull horns and

divinity is well attested in the religious art of Mesopotamia,

Anatolia and Levant, and to a degree Egypt too. Bulls are prominently

featured in the art of Minoan Crete as well. This is also why the

biblical golden calf is, well, a calf.

Baal Hadad’s family

tree is rather confusing, with two separate gods being called his

fathers in the Baal Cycle and other texts. The interpretation can

potentially be complicated by the fact that Ugarit’s (and other bronze age kingdoms’) kings seemingly

often called monarchs they viewed as more powerful as „fathers”

and these of similar perceived prestige as „brothers” in

diplomatic correspondence. For example, one can operate undeer the assumption the god Dagon was Baal’s actual father (he’s

only ever brought up in such a context, and shared many of Baal’s

roles, and like him was a prominent god deeper inland as well) while

El, the elderly king of the gods, was only Baal’s „father” in the

diplomatic sense of the term. Some scholars instead propose that

Dagon and El were partially or fully syncretised in Ugarit, that mention of Dagan was a nod to foreign tradition, or even

that Baal having two fathers might be the echo of the myth of Baal’s

Hittite counterpart.

Our main source of information about Baal

is the Baal cycle, a heroic epic recovered from Ugarit in the 1920s

and a subject of much scholarly analysis ever since. While not

perfectly preserved, it is nonetheless a very valuable source of

information, and arguably it’s what allowed Baal to metaphorically

speak in his own voice to modern researchers. It details his struggle

with various enemies seeking to ruin his dream of becoming the king

of the gods.

While it’s hard to tell if that was the intent

of the ancient writers, Baal appears as somewhat of an underdog in

this myth – his posdible father doesn’t seem to be a god of particular

importance, he has to rely on his allies to accomplish most of his

heroic deeds, he whines about having no house of his own, and his

actions are often impulsie. However, this shouldn’t overshadow the fact he was for the most part the most popular god of Ugarit.

Figures associated with the

Ugaritic Baal include:

- Anat - a war goddess who shares Baal’s impulsive nature, and in myths frequently acts as his main ally or enforcer, slaying various sea monsters and the personification of death, Mot (however, there are a few instances showing Baal siding with humans rather than with Anat). She’s often referred to as Baal’s sister, and sometimes argued to also be his consort, though this view is challenged nowadays by some researchers. It should be noted that while Baal is firmly established as Dagon’s son, Anat is never presented as related to the latter – she is pretty firmly only a daughter of El and, implicitly, his wife Asherah.

- Ashtart - the Ugaritic forerunner of the famous Phoenician Astarte. She was equated with Babylonian Ishtar, and while she’s not as prominent as Anat in Ugaritic texts, they emphasize her roles as a warrior and hunter; she is however also renowned for her beauty. In the Baal Cycle she berates Baal for his insufficient determination during the battle with his first opponent, and later announces his victory to the world. In many texts, both in Ugarit and beyond, her epithet is “face of Baal,” implying a particularly close bond between these two figures – it is plausible that she was viewed as Baal’s consort in Ugarit. Ashtart/Astarte is NOT the same figure as Asherah (technically Athirat), the Canaanite mother goddess, and both of them appear in the Baal cycle in different roles.

- Kothar-wa-Khasis – a craftsman god, indirectly equated with and possibly in part derived from Egyptian Ptah – myths state outright that he lives in Memphis, where Ptah’s main temple was located. He acts as a reliable ally to Baal, providing him with weapons and precious objects and eventually also building his palace. In one scene, an argument occurs between him and Baal over whether the palace needs windows:

- Yam – the god of the sea, also serving as Baal’s rival to the throne. Various passage of the myth and other texts portray him as violent, tyrannical and otherwise unpleasant, and his overthrow by Baal as a positive development. He’s aided by a number of sea monsters, the most notable of which is the serpent Lotan. It has been argued that that the later Babylonian Tiamat was in part based on him or his counterparts, as she doesn’t appear in any Babylonian sources earlier than Enuma Elish, which is a work younger by a few centuries than the Baal cycle.

- Mot – a personification of death and desolation. While even Yam received some reverence and offerings, Mot did not – he only existed as an antagonist for heroic figures. Mot’s main trait is his insatiable hunger.

While the Baal from Ugarit is, due to

possessing his own heroic epic, the most famous and probably best

researched today, he was by no means the only deity of this sort –

most cities in the Levant (and beyond, in other areas settled by the

Phoenicians) had their own tutelary gods, often referred to as Baals.

Among these, notable

examples include:

- The Baal of Tyre – Melqart served as the lead deity of the city of Tyre, seemingly the most prominent of the Phoenician centers. His name seems to simply mean “lord of the city”. He was a god of many things, most notably being viewed as a culture hero who discovered the secret of producing the purple dye which made Phoenician city-states rich and prosperous. He was also an underworld deity, and as a result an association with Babylonian Nergal has been proposed. It’s quite likely that the Tyrian Baal was the one mentioned in some Biblical accounts – for example, Jezebel was said to be a princess of Tyre, therefore it’s plausible that the god she revered was the Tyrian Baal. Greeks regarded him as analogous to Heracles, sadly I am unable to find the explanation for this.

- The Baal of Sidon – Eshmun, a healing deity. He was seemingly viewed as analogous to the Mesopotamian Tammuz, Ishtar’s lover condemned to torment in the underworld in her place. The origin of his name is unclear. His myth is somewhat similar to that of Phrygian Attis – the goddess Astronoë (possibly a variant of Astarte/Ishtar) was madly in love with him, but he was, to put it lightly, not interested (unlike Attis), and eventually castrated himself to show that, which lead to his death. He was restored to life (also unlike Attis) and made into a god of healing. Melqart and Eshmun were the two Phoenician gods invoked in a treaty meant to guarantee peace between the coastal regions and Assyria, which shows the high status of their cities in antiquity.

- The Baalat of Gebal (Byblos) – Baalat was the feminine form of Baal, and a title sometimes simply applied to any prominent goddess. However, the Baalat of Gebal was seemingly a separate deity, associated with this epithet in the same way as Ugarit’s Hadad became inseparable from his title of Baal. Some researchers instead propose she was simply Ashtart/Astarte, though Anat, Asherah, and Egyptian Isis and Hathor (while Ugarit was a Hittite or Mittani vassal, Gebal was under Egyptian control) were also proposed as her true identity based on instances of historical syncretism. However, due to very few surviving documents, her exact nature remains puzzling.

- Baal Shamin - revered not only by Phoenicians and their ancestors, but also by Nabateans. He was likely initially simply an epithet of Baal Hadad, but developed into a distinct deity in later times. As a separate figure he was the lead god of Palmyra, though he was eventually upstaged by Bel (Marduk) there.

- The Baal of Carthage, Hammon - unlike the generally youthful other Baals, he was depicted as an old man. He was also regarded as the father of Melqart, with the latter viewed as a more important deity – Carthage in fact paid tribute to his Tyrian temple. Most of what we know about him comes from Roman sources, and as a result it’s hard to tell what was his true nature – it has been proposed he was a sun god at first. He was equated by Greeks with Cronus.

In a way, Babylonian Marduk

can be considered to be a Baal – among the titles used to refer to

him was “Bel,” the equivalent of “Baal,” and like the coastal

Baals he was originally simply the protective deity of a specific city. However,

occasional attempts to identify Marduk as originally having roughly

the same nature as Adad/Hadad – that of a weather and agriculture

god – are generally not considered to be credible by modern

researchers. As I already noted, it is however quite likely that

Marduk’s battle with Tiamat – a figure invented for the Enuma Elish

– was at least in part based on Baal’s fight with Yam in the Baal

cycle.

Sadly, the dubious claims that Tiamat represents a

deposed matriarchal order seem to be much more known to the general

public – as I already said on my blog before, these are nonsensical

and their spread relies on limited understanding of Mesopotamian

history. Enuma Elish was not a primordial text, but a myth devised

relatively late to further help with increasing Marduk’s status by

having him perform the same acts as many other popular gods, there is

also no evidence of the existence of an earlier matriarchal religion

in Sumerian and Akkadian sources.

Curiously, it’s also

possible the myth of Baal and its analogs and derivatives inspired

Zeus’ battle with Typhon – it is sometimes said that it took place

near mount Saphon, associated with the cult of Baal Hadad and

specifically with his battle against Yam.

Egyptians regarded Baal as

analogous to Seth – this conflation occurred before Seth’s

dominant role became that of an opponent of Osiris of his family, and

relied on Seth being a god of the borderlands and foreigners

inhabiting them, as well as on his chaotic, impulsive nature.

Possibly depictions of Seth as the opponents of the serpent Apep were

a factor, too. In an Egyptian adaptation of the Ugaritic Baal cycle,

the so-called Astarte papyrus, Seth battles Yam, though no outright

conflation of the Ugaritic and Egyptian mythical evildoers ever

occurred to my knowledge. Baal’s supporting cast of Anat and Astarte

was likewise associated with Seth in Egypt, and both are referred to

as his consorts in Egyptian texts.

Outside of this specific

example of syncretism, “Seth” was also sometimes used as a

generic title for foreign gods, almost the same was as Baal

functioned as a title in the Levant – it was applied to various

Canaanite gods, but also to the gods of the Hittites. For example the peace treaty between Ramses II and Hattusili XI mentions “Seth of the

city of Zipalanda” and “Seth of the city of Arinna” -

corresponding Hittite text reveals that these are simply Teshub, the

Hurrian an Hittite monster-slaying thunder god (and close analog of

Ugaritic Baal Hadad – as Ugarit was seemingly at least for some

time a Hittite dependency, it is more than likely their myths

influenced each other), and the sun goddess of Arinna. Egyptians

referred to the Libyan god Ash as a Seth, too. Curiously, at least

one Ugaritic text identifies the city’s Baal with Amun, rather than

Seth – it doesn’t seem like this idea caught on in Egypt, though.

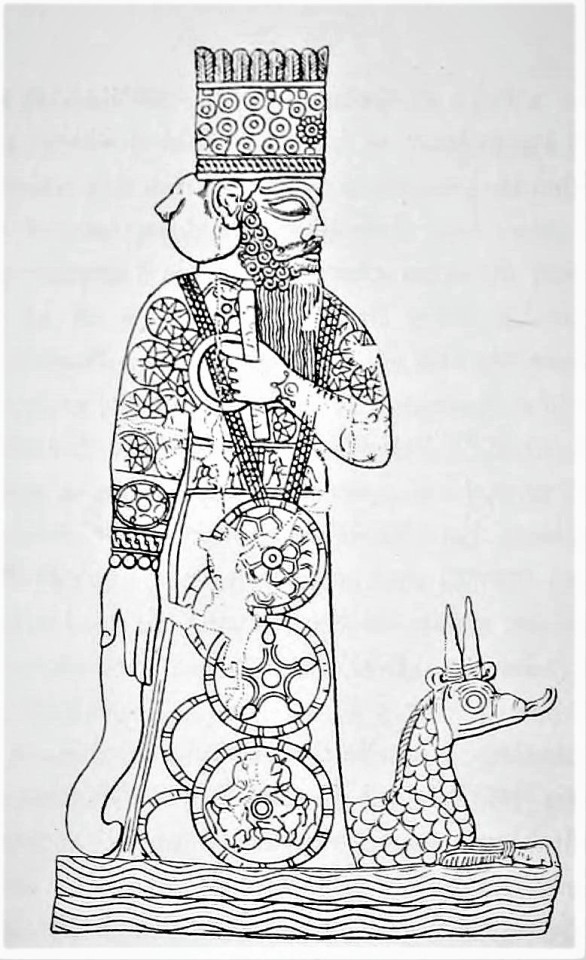

Teshub was possibly the

deity closest to Baal Hadad both in terms of myths and depictions –

compare the one above with the Ugaritic Baal stele from much earlier in

this article – but as a little known figure he (and his most

notable allies and enemies) deserves his separate post, so I will not

discuss him there, beyond letting you know that while Baal simply

clobbered Yam with some encouragement from friends, Teshub only

managed to best the serpent monster Illuyanka by having his son seduce

Illuyanka’s daughter in order to recover his internal organs stolen

by the snake. Even functionally similar deities can have wildly different

stories behind them!

Further

reading (most articles available on academia edu, jstor or persee):

- A Moratorium on God Mergers? The Case of El and Milkom in the Ammonite Onomasticon by Collin Cornell

- Animal sacrifice at Ugarit by Dennis Perdee

- The Lady of the Titles: The Lady of Byblos and the Search for her “True Name” by Anna Elise Zernecke

- Ugaritic monsters I: The ˁatūku “Bound One” and its Sumerian parallels by Madadh Richey

- ‛Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts by Mark S. Smith

- ʿAthtartu’s Incantations and the Use of Divine Names as Weapons by Theodore J. Lewis

- Baal, Son of Dagan: In Search of Baal’s Double Paternity by Noga Ayali-Darshan

- The Role of Aštabi in the Song of Ullikummi and the Eastern Mediterranean “Failed God” Stories by Noga Ayali-Darshan

- The Death of Mot and his Resurrection in the Light of Egyptian Sources by Noga Ayali-Darshan

- The Other Version of the Story of the Storm-god’s Combat with the Sea in the Light of Egyptian, Ugaritic, and Hurro-Hittite Texts by Noga Ayali-Darshan

- The storm-gods of ancient Near East: summary, synthesis, recent studies, parts 1 and 2 by Daniel Schwemer

- Politics and Time in the Baal Cycle by Aaron Tugendhaft

- Echoes of the Baal Cycle in a Safaito-Hismaic Inscription by Ahmad Al-Jallad

- My neighbor’s god: Assur in Babylonia and Marduk in Assyria by Grant Frame

- Gods in translation. Dynamics of transculturality between Egypt and Byblos in the III millennium BC by Angelo Colonna

- Zeus Kasios or the Interpretatio Graeca of Baal Saphon in Ptolemaic Egypt by Alexandra Diez de Oliveira

water-screen liked this

fairrydairry liked this

alprerena liked this

quanreblogs reblogged this from yamayuandadu

quanblovk liked this

akishounen liked this

akishounen liked this nobodyimportant14 liked this

thelvwitchkimmie86 liked this

thelvwitchkimmie86 liked this  wiseowlmyths reblogged this from yamayuandadu

wiseowlmyths reblogged this from yamayuandadu starsoftheabyss liked this

elizabeth-halime reblogged this from yamayuandadu

sixteendee liked this

predestinationblues liked this

aliliceswonderland reblogged this from yamayuandadu

duckpasta-kamonabe liked this

oroborospaghettiwithmeatballs reblogged this from eirikrjs

oroborospaghettiwithmeatballs liked this

deltagalacticdaydreamer liked this

infinitereghretti liked this

infinitereghretti liked this guygirder liked this

technoreliquary reblogged this from giegues

technoreliquary liked this

hmoneytuts liked this

siesta-deprived liked this

zeroabyss reblogged this from yamayuandadu

zeroabyss reblogged this from yamayuandadu  zeroabyss liked this

zeroabyss liked this starallia liked this

vanillaicefuture liked this

nicht-alles-gold liked this

alephskoteinos liked this

borgniner liked this

eirikrjs reblogged this from yamayuandadu

jackdollnan liked this

askdacast liked this

evander2511 reblogged this from yamayuandadu

evander2511 liked this

artsymoth liked this

artsymoth liked this treestar liked this

gentledeathsblog reblogged this from yamayuandadu

gentledeathsblog liked this

elizabeth-halime liked this

splashonabitch liked this

yamayuandadu posted this

yamayuandadu posted this - Show more notes