Darfur: Blueprint for Genocide - Archipielago Libertad

Darfur: Blueprint for Genocide - Archipielago Libertad

Darfur: Blueprint for Genocide - Archipielago Libertad

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Darfur</strong>:<br />

<strong>Blueprint</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Genocide</strong><br />

November 2004<br />

Dr James M. Smith<br />

Ben Walker<br />

Report No. R01/04

Founded in 2000, the Aegis Trust dev eloped from the work of the Holocaust Centre inNottinghamshire (opened in 1995). Aegis<br />

addresses causes and consequences of genocide and crimes against humanity. It w orks closely with surv ivors, educationalists,<br />

academics and policy makers in areas relating to genocide education, research and prevention.<br />

The memorial centres, both in the UK and Rwanda, are important to the w ork of Aegis. They are a reminder of the terrible<br />

consequences that ensuewhen the world does not prevent genocide. They also give dignity to the victims and provide a voice<br />

<strong>for</strong> survivors, who are often overlooked. This helps reverse some of the dehumanisation that takes place during genocide and<br />

contributes to rehabilitation. It recognises that the legacy of genocide continues long after the killing stops.<br />

The Aegis Institute<br />

Lound Hall<br />

Bothamsall<br />

Ret<strong>for</strong>d<br />

DN22 8DF<br />

Tel: 01623 862592<br />

Email: james.smith@aegistrust.org<br />

RegCharity No.1082856<br />

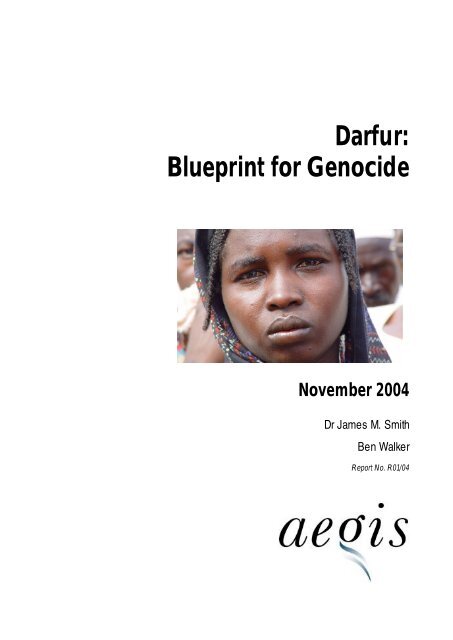

Cover photo: A woman in Breidjing refugee camp, eastern Chad, July 2004. Her<br />

husband had been killed six months earlier. © James M. Smi th, Aegis Trust.

Authors:<br />

Dr James M. Smith is Chief Ex ecutive of the Aegis Trust (see inside cov er) and co-founder of the UK Holocaust Centre.<br />

He directed the project to establish the Kigali <strong>Genocide</strong> Memorial Centre in Rwanda which opened in April 2004, and was<br />

co-editor of Will <strong>Genocide</strong> Ever End? published by Paragon House in associationwith Aegis in 2003.<br />

Ben Walker is a Development Studies graduate of Leeds University and Research Assistant at the Aegis Institute.

CONTENTS<br />

iv<br />

Table of Contents<br />

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VII<br />

SECTION 1<br />

NAMING THE CRISIS: POLICY IMPLICATIONS 1<br />

1.1 Naming it 1<br />

1.2 Crimes against humanity 1<br />

1.3 <strong>Genocide</strong> 2<br />

1.4 Ethnic cleansing 2<br />

1.5 Dodging the ‘g’ word 3<br />

1.6 ‘Genocidal crisis’: a usefulmanagement term 3<br />

1.7 Management implications once the term ‘genocidal’ is applied 4<br />

1.8 Hiding behind the humanitarian crisis 4<br />

1.9 Isn’t genocide just ex treme conflict? 5<br />

1.10 But isn’t there a civil war? 5<br />

SECTION 2<br />

DARFUR AND THE IDEOLOGY OF SUDAN 6<br />

2.1 Arabization and Islamization 6<br />

2.2 Precedents of genocidal acts in Sudan 7<br />

2.3 Acomment on ethnicity: Arabs and Africans? 8<br />

2.4 Thesignificance of exclusionary ideology 9<br />

2.5 Exclusionary ideology in <strong>Darfur</strong> 9<br />

SECTION 3<br />

SYSTEMATIC ACTIONS AMOUNTING TO GENOCIDE 13<br />

3.1 Ideas influence action 13<br />

3.2 Genocidal acts in thecurrent crisis 14<br />

3.3 How the InternationalCommunity has defined the situation 19<br />

SECTION 4<br />

SECURITY 21<br />

4.1 Securing populations at risk as a priority 21<br />

4.2 International response to security 22

Table of Contents<br />

4.3 Chronology of the security and political dialogue – 2004 23<br />

4.4 British policy 26<br />

4.5 Political settlement and security 26<br />

SECTION 5<br />

ENDING IMPUNITY 28<br />

5.1 Who is incontrol? 28<br />

5.2 Countering the genocidal threat with judicial process 28<br />

CONCLUSION 31<br />

RECOMMENDATIONS AND QUESTIONS 31<br />

APPENDICES 32<br />

Appendix A: Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of theCrime of <strong>Genocide</strong> 33<br />

Appendix B: Definitions of the Actions Constituting Crimes Against Humanity 36<br />

Appendix C: Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum 2004 37<br />

Appendix D: October 1987 Letter to Sadiq Al Mahdi - Sudanese Prime Minister 1986-89 (Translated from Arabic) 38<br />

Appendix E: List Compiled by the Son of the Last Sultan of <strong>Darfur</strong> of Villages Evacuated by Force between 2000<br />

and 2002 39<br />

Appendix F: List of Attacks on Villages Compiled by Fur MPs 44<br />

Appendix G: Breakdown of Security and Political Dialogue by Month 49<br />

Appendix H: List of Reports Providing Evidence of GoS Culpability 61<br />

Appendix I: List of Janjaweed Camps with Locations and Names of Commanders 62<br />

Appendix J: Secret Circular Issued by the Ex ecutive Committee of Arab Gathering (1988) 65<br />

Appendix K: Orders Issued by the Arab GatheringUnifiedMilitary Command 66<br />

Appendix L: AReport on the Relationship between the Fur tribe and theNational Islamic Front 67<br />

Appendix M: Quraish 2 - Arab Congress Circular 71<br />

Appendix N: Government Letter 73<br />

Appendix O: Recommendations following fourmeetings of the Arab Gathering PoliticalCommittee with Local<br />

Councils 74<br />

v

TABLE OF ACRONYMS<br />

vi<br />

AU African Union<br />

DfID Department <strong>for</strong> International Dev elopment<br />

EU European Union<br />

FCO Foreign and Commonw ealth Office<br />

GoS Gov ernment of Sudan<br />

HMG Her Majesty ’s Gov ernment<br />

HRW Human Rights Watch<br />

ICC International Criminal Court<br />

ICG International Crisis Group<br />

IDP Internally Displaced Persons<br />

JEM Justice and Equality Mov ement<br />

MSF Médecins sans Frontières<br />

NCP National Congress Party<br />

NGO Non-gov ernmental organisation<br />

NIF National Islamic Front<br />

OHCHR Office of the High Commission <strong>for</strong> Human Rights<br />

PAIC Pan-Arab Islamic Conference<br />

PDF Popular Defence Force<br />

SLA Sudan Liberation Army<br />

SPLA/M Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement<br />

UN United Nations<br />

UNHCHR United Nations High Commission <strong>for</strong> Human Rights<br />

UNPROFOR United Nations Protection Force<br />

USAID United States Agency <strong>for</strong> International Dev elopment<br />

Table of Acronyms

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

Executive Summary<br />

International law allows wide scope <strong>for</strong> preventing genocide. There are huge moral and political obligations to do so.<br />

The United Nations <strong>Genocide</strong> Convention (1948) sets a clear legal framework enabling prevention. Resolve and action to<br />

prev ent depend, however, on the politicalw ill to do so.<br />

The presence of an exclusionary ideology (usually meaning institutionalised or organised racism) helps to differentiate<br />

a genocidal situation from a two-sided conflict. <strong>Genocide</strong> is organised violence on a massive scale, but it is more akin to<br />

ex treme racism than ex tremeconflict.<br />

Exclusionary ideology sets the scene <strong>for</strong> future genocide. It justifies in the mind of a dominant group extreme measures<br />

that can be taken against the perceived inferior and vulnerable group. What matters in a genocidal situation is how a<br />

dominant group perceives both itself and the vulnerable group. Perpetrators of genocide do not invent the identity of<br />

groups, but they are obsessedwith identify . They augment it, simplify it andcreate an enemy.<br />

<strong>Darfur</strong> is suffering the outcomes of ethnic and tribal conflict, power struggles and competition <strong>for</strong> land. In recent decades,<br />

how ever, an exclusionary ideology has driven policies of the current and previous Government of Sudan (GoS) that have<br />

led to jihad and outcomes that can be regarded as genocide.<br />

The crisis in <strong>Darfur</strong> is happening in that context and is also driven by the supremacist / racist ideas of the Arab Gathering,<br />

ideas congruent w ith those of central government in Khartoum. (Arab Gathering documents which as yet Aegis has not<br />

been able to authenticate are presented in the Appendices. How ever, we believe it is likely that these are genuine<br />

documents and regard it as important that they are seen.) Since the emergence of these ideas in a letter addressed to the<br />

Sudanese Prime Minister in 1987 (See Appendix D), v iolence against Africans in Western Sudan has increased and<br />

becomemore organised.<br />

In <strong>Darfur</strong>, despite the complexity of ethnicity that ex ists, Arab supremacists are now promoting the words ‘Zurga’ (nigger)<br />

and ‘Abid’ (slav e), drawing on stereoty pes and discrimination of the past where an ‘African’ identity was regarded as being<br />

synonymous with slav e.<br />

When civilians are being systematically targeted during a crisis and an exclusionary ideology exists, recognising the<br />

genocidal threat is more important than defining a situation as genocide. In such a situation, the crimes being committed<br />

may be referred to as crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing or genocide. Such instances should be described as<br />

genocidal regardless of whether a consensus is reached about whether it is genocide or not. The political and moral<br />

obligations to prevent are as strongwhen genocide is threatened, as when it is agreed that it is happening. Indeed by the<br />

time the situation is defined, it may be too late to prevent. So the term genocidal may be used to indicate a risk<br />

assessment, not provide a legal conclusion.<br />

The term genocidal should signify a change in the priorities in the management of the crisis. In such a situation, security<br />

<strong>for</strong> those at risk must be regarded as much a priority as providing humanitarian aid and achieving political settlement. In a<br />

genocidal situation, compromisingsecurity in fav our of peace-talks may cost lives.<br />

In <strong>Darfur</strong> either the GoS was actively supporting the Janjaweed or it had lost control of them. Both scenarios demanded<br />

outside help. The InternationalCommission <strong>for</strong> Interv ention and State Sov ereignty concluded in 2001 that w hen sovereign<br />

states are unwilling or unable to protect their own citizens, the responsibility must be borne by the broader community of<br />

states. Yet it was the Government of Sudan that w as asked by the United Nations (UN) to provide protection <strong>for</strong> the<br />

vulnerable. Attacks on internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in November by Sudanese security <strong>for</strong>ces demonstrate<br />

that the need <strong>for</strong>security is as pressing as ever.<br />

vii

viii<br />

Executive Summary<br />

Insecurity <strong>for</strong> those under threat of genocide and impunity <strong>for</strong> international crimes is a combination that allows<br />

gov ernments to get away with murder. When a conflict is recognised as genocidal in nature, addressing this duo must<br />

become central to the management of the crisis. Both have been insufficiently prioritised in managing the crisis in<br />

<strong>Darfur</strong>; this has impeded ef<strong>for</strong>ts to prevent genocide.<br />

The British Government has been careful not to blame the GoS. But if there is broad consensus that the GoS bears<br />

responsibility <strong>for</strong> mass murder, why is there not an unequivocal message that the perpetrators w ill be brought to<br />

account? Granted it is not helpful or practical to indict the Government. But the senior figures involved directly in the<br />

atrocities in <strong>Darfur</strong> should be brought to account.<br />

Asking the GoS to ‘rein in’ those responsible must have given the Janjaweed perpetrators great com<strong>for</strong>t. Because the<br />

world does not hav e the moral strength to end impunity or protect the v ulnerable, we have to rely on probable<br />

sponsors of genocide to provide security .<br />

Now that the mandate of 3000 African Union (AU) soldiers in <strong>Darfur</strong> has been slightly ex tended, wealthy nations<br />

should support an increase in the number of AU troops to around ten times the current number, in line with the<br />

recommendations of Gen. Romeo Dallaire. A no-fly zone is now really too late, nonetheless should be imposed and<br />

monitored.<br />

The UN and member states hid behind the humanitarian aid ef<strong>for</strong>t. The need to protect citizens in <strong>Darfur</strong> was<br />

understood more in the African Union than it was among the wealthy member states, including the UK. However the<br />

AU mission languished in an under-resourced state, atrocities continued and even the recently expanded <strong>for</strong>ce is still<br />

a sub-optimal arrangement to avert the threat of ‘genocide by attrition’.<br />

Political settlementwill always be harder to achieve if security <strong>for</strong> those under threat is not prov ided concurrently. In<br />

a climate of fear it has been predictably hard to keep the Sudan Liberation Army and the Justice and Equality<br />

Movement around the negotiating table.<br />

Justice is often perceived as a post-conflict issue. Impunity, though, in a genocidal situation is a brother to insecurity;<br />

both tell the perpetrator that there is insufficient resolve or political w ill to stop genocide. Allowing impunity <strong>for</strong> past<br />

atrocities in the South of Sudan and in the NubaMountains has contributed to the crisis in <strong>Darfur</strong>.<br />

Documentation is the first step in bringing about accountability . But a library of reports will not end impunity if there is<br />

no resolve <strong>for</strong> it to lead somewhere. International inquiries have in the past led to the <strong>for</strong>mation of ad hoc tribunals.<br />

The US refusal to support the International Criminal Court (ICC) is not helpful in ending impunity in <strong>Darfur</strong> and the<br />

Security Council should have referred the situation in <strong>Darfur</strong> to the prosecutor of the ICC once the systematic nature<br />

of the atrocities w as known. Once the International Commission of Inquiry has finished, member states should be<br />

encouraged not to veto or abstain regarding an ICC referral.<br />

While we are focussed on the crisis, we need to be mindful that long term, the problems of Sudan lie in the neglect,<br />

underdevelopment and inequality in the regions that allow the racism and hostility to be fostered. Sudan will never be<br />

at rest until these are addressed together and aggressively. Aegis Trust v iews a federal Sudan as a helpful, stable<br />

way <strong>for</strong>ward but that is <strong>for</strong> the Sudanese to determine. Whatever route they take, justice and equality will be a good<br />

foundation <strong>for</strong> the future.<br />

Upholding international law at an early stage in this genocidal process by referring the situation in <strong>Darfur</strong> to the ICC<br />

could have deterred the perpetrators. So far, the perpetrators are not trembling in fear of justice.<br />

Despite the 1948 Convention (Appendix A) and the signing of the Stockholm Declaration inJanuary 2004 (Appendix<br />

C), and despite many great ef<strong>for</strong>ts by governments and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in respect of the<br />

humanitariancrisis in <strong>Darfur</strong>, the genocidal crisis remains ex tremely difficult tocontain or mitigate without a massive<br />

shift in politicalw ill. Leo Kuper’s contention continues to bear truth: that gov ernments still hav e the ‘sovereign right to<br />

commit genocide’.

The Aegis Trust recommends that:<br />

Executive Summary<br />

• Security <strong>for</strong> civilians subject to genocidal acts in <strong>Darfur</strong> be prioritised through:<br />

o a ten-fold ex pansion of the AU <strong>for</strong>ce and a strengthening of its mandate to include<br />

disarmament of the Janjaw eed militia, or at least superv ision of disarmament by the<br />

Gov ernment of Sudan.<br />

o A no-fly zone to imposed immediately by the UN, to be en<strong>for</strong>ced by the AU with finance<br />

and resources from w ealthy UN member states.<br />

• Serious ef<strong>for</strong>ts shall be made to address impunity:<br />

o Preferably the UN Security Council should refer the situation in <strong>Darfur</strong> to the ICC.<br />

o If referral to the ICC prov es impossible due to political opposition, av iable alternativ e<br />

should be put <strong>for</strong>w ard to end the impunity of perpetrators of acts of genocide and crimes<br />

against humanity in <strong>Darfur</strong>.<br />

• Long term underly ing causes of the crisis must be addressed:<br />

o Long term, a comprehensive plan should be agreed to reverse the underly ing causes of<br />

the crisis, namely the inequality and marginalisation within <strong>Darfur</strong>. A significant<br />

dev elopment package is required that benefits all groups equally.<br />

o Political empow erment through a federal system in Sudan may prevent a mov ement<br />

tow ards autonomy in the West whichw ould lead to greater conflict and the<br />

fragmentation of Sudan in the future.<br />

ix

SECTION 1<br />

Naming the Crisis: Policy<br />

Implications<br />

“It’s genocide”, “It’s ethnic cleansing”, “It’s crimes<br />

against humanity”, “It’s tribal war”<br />

Quite a lot, it seems, is in a name.<br />

While it is the view of the Aegis Trust that the events in<br />

<strong>Darfur</strong> during this year amount to genocide under the UN<br />

<strong>Genocide</strong> Convention (Appendix A), we recognise that<br />

getting wound up in legal debates about definitions while<br />

people perish may not help the management of the crisis.<br />

Sav ing lives should take priority over achieving a legal<br />

consensus.<br />

The ev idence is quite clear: somebody wants to ‘get rid’ of<br />

Africans from <strong>Darfur</strong>. Does it matter so much what we call<br />

it? On the one hand, yes, because we should not mince<br />

words – weshould callsomething by its proper name.<br />

Calling a crisis ‘genocide’ ought to create certain<br />

obligations to respond (See 1.3).<br />

How ever, if w e cannot agree that genocide itself is<br />

happening, then it will be helpful to describe such a crisis<br />

as ‘genocidal’ (see 1.4).<br />

1.1 Naming it<br />

To date the European Parliament, the United States and<br />

Germany have all called the situation in <strong>Darfur</strong> genocide.<br />

Most states, however, have taken the position that they<br />

are w aiting <strong>for</strong> the outcome of the International<br />

Commission of Inquiry ordered by UN Resolution number<br />

1564, due to report in January 2005. Few human rights<br />

NGOs have called the situation genocide. Notable<br />

exceptions include <strong>Genocide</strong> Watch, the Physicians <strong>for</strong><br />

Human Rights in the US and Jubilee Action in the UK.<br />

International Crisis Group has not done so on the basis<br />

that prov ing genocide involves difficult legal issues<br />

essentially about ‘intent’ w hich can only be resolved by a<br />

court. 1 Amnesty International has chosen not to on similar<br />

1 See Conclusion to Section 3. Intent can be deduced from sufficient<br />

evidence. Combined with the existence of an exclusionary ideology in <strong>Darfur</strong>,<br />

the evidence in <strong>Darfur</strong> is enough <strong>for</strong> Aegis to conclude that genocide is<br />

happening there. It is certainly enough <strong>for</strong> us to conclude that genocide is a<br />

very real and urgent threat.<br />

1<br />

grounds, saying that it is not prepared to do so based on<br />

its current in<strong>for</strong>mation.<br />

The International Commission of Inquiry is likely to apply<br />

one of the follow ing three labels to the crisis in <strong>Darfur</strong>:<br />

• Crimes against humanity<br />

• <strong>Genocide</strong><br />

• Ethnic cleansing<br />

1.2 Crimes against humanity<br />

Crimes against humanity are defined in the Principles of<br />

the Nuremberg Tribunal as:<br />

Murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation<br />

and other inhuman acts done against any civilian<br />

population, or persecutions on political, racial or<br />

religious grounds, when such acts are done or such<br />

persecutions are carried on in execution of or in<br />

connection with any crime against peace or any war<br />

crime. 2<br />

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court<br />

defines crimes against humanity as:<br />

Any of the following acts when committed as part of<br />

a widespread or systematic attack directed against<br />

any civilian population, with knowledge of the<br />

attack:<br />

(a) Murder;<br />

(b) Extermination;<br />

(c) Enslavement;<br />

(d) Deportation or <strong>for</strong>cible transfer of population;<br />

(e) Imprisonment or other severe deprivation of<br />

physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of<br />

international law;<br />

(f) Torture;<br />

(g) Rape, sexual slavery, en<strong>for</strong>ced prostitution,<br />

<strong>for</strong>ced pregnancy, en<strong>for</strong>ced sterilization, or any<br />

other <strong>for</strong>m of sexual violence of comparable gravity;<br />

(h) Persecution against any identifiable group or<br />

collectivity on political, racial, national, ethnic,<br />

cultural, religious, gender as defined in paragraph 3,<br />

or other grounds that are universally recognized as<br />

impermissible under international law, in connection<br />

with any act referred to in this paragraph or any<br />

crime within the jurisdiction of the Court;<br />

(i) En<strong>for</strong>ced disappearance of persons;<br />

(j) The crime of apartheid;<br />

2 Principles of the Nuremberg Tribunal (1950), Principle VI.

(k) Other inhumane acts of a similar character<br />

intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to<br />

body or to mental or physical health. 3<br />

The terms in this paragraph are defined in Appendix B.<br />

1.3 <strong>Genocide</strong><br />

Defined as acrime in international law: UN Conv ention on<br />

the Prev ention and Punishment of the Crime of <strong>Genocide</strong><br />

(1948) andRome Statute of the ICC (2002):<br />

In the present Convention, genocide means any of<br />

the following acts committed with intent to destroy,<br />

in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or<br />

religious group as such:<br />

(a) Killing members of the group;<br />

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to<br />

members of the group;<br />

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of<br />

life calculated to bring about its physical destruction<br />

in whole or in part;<br />

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births<br />

within the group;<br />

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to<br />

another group. 4<br />

The UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of<br />

the Crime of <strong>Genocide</strong> allows states to prev ent genocide<br />

(see Appendix A). Signatories to the Convention<br />

undertake to prevent and punish the crime of genocide<br />

(see Article I of Appendix A).<br />

The Convention creates a huge moral and political<br />

obligation to prevent genocide. This was recognised by<br />

the fifty -fiv e member states. It is not specific about how<br />

states can prevent genocide, as the mechanisms to<br />

commit the crime may vary, but it does set a clear legal<br />

framework to enable them to do so, usingw hatev er organs<br />

of the UN are necessary (Article VIII, Appendix A).<br />

The Convention gives a huge amount of licence: states<br />

can call upon the UN organs to take action… as they<br />

consider appropriate… <strong>for</strong> the prevention and<br />

suppression… of acts of genocide (Article VIII,<br />

Appendix A).<br />

It goes further and says that this applies even to attempts<br />

to commit genocide or to complicity in genocide (Article<br />

III).<br />

3 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Article 7.<br />

4 Office of the High Commissioner <strong>for</strong> Human Rights, Convention on the<br />

Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of <strong>Genocide</strong>,<br />

http://www.ohchr.org/english/law/genocide.htm [Accessed 16 November<br />

2004].<br />

Section 1: Naming the Crisis: Policy Implications<br />

1.4 Ethnic cleansing – a <strong>for</strong>m of<br />

genocide<br />

For some bizarre reason, this term causes many of us –<br />

the media, policy people and NGOs – to breathe a sigh of<br />

relief, as if it is not so urgent. ‘It’s OK, its not genocide<br />

after all; it’s just ethnic cleansing.’<br />

Actually, the reverse ought to be true. Ethnic cleansing is<br />

an appalling act of organisedv iolence. It includes <strong>for</strong>cible<br />

population transfer (also an international crime under the<br />

Geneva Convention IV, Article 49 and a crime against<br />

humanity according to the Rome Statute of the ICC), but<br />

should not bemistaken as that alone.<br />

During the Bosnian war of the mid-1990s, the Serb<br />

nationalists wanted to ‘get rid’ of the Bosnian Muslims.<br />

What they did to accomplish that amounted to war crimes,<br />

crimes against humanity and genocide. It w as the lawyers<br />

in the end who decided. In the meantime, ‘ethnic<br />

cleansing’ was the term commonly applied.<br />

Unlike genocide and crimes against humanity, enshrined<br />

in Conventions and Statutes, ethnic cleansing is not really<br />

defined as a single crime. In 1993 a UN Commission of<br />

Ex perts has described it as:<br />

rendering an area ethnically homogenous by using<br />

<strong>for</strong>ce or intimidation to remove persons of given<br />

groups from the area. 5<br />

That sounds like <strong>for</strong>cible population transfer, but in their<br />

final report, the Commission expanded on this:<br />

Based on the many reports describing the policy<br />

and practices conducted in the <strong>for</strong>mer Yugoslavia,<br />

‘ethnic cleansing' has been carried out by means of<br />

murder, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention,<br />

extra-judicial executions, rape and sexual assaults,<br />

confinement of civilian population in ghetto areas,<br />

<strong>for</strong>cible removal, displacement and deportation of<br />

civilian population, deliberate military attacks or<br />

threats of attacks on civilians and civilian areas, and<br />

wanton destruction of property. Those practices<br />

constitute crimes against humanity and can be<br />

assimilated to specific war crimes. Furthermore,<br />

such acts could also fall within the meaning of the<br />

<strong>Genocide</strong> Convention. 6<br />

Ethnic cleansing, then, is more than moving one<br />

population from one place to another. The methods used<br />

to move them are vicious and are intended to kill, maim,<br />

subjugate and destroy people and property. It fits v ery<br />

closely w ith the definition of genocide provided by the UN<br />

<strong>Genocide</strong> Convention. That’s not surprising as it stems<br />

5 UN Commission of Experts, First Interim Report, 10 February 1993.<br />

6 UN Commission of Experts (1994), Final Report of the Commission of<br />

Experts.<br />

2

from a desire by perpetrators to ‘get rid’ of a group of<br />

people.<br />

Significantly, the Convention recognises the threat of<br />

genocide even be<strong>for</strong>e it is full-scale. In the example of the<br />

Holocaust (which helped to define the crime of genocide)<br />

separating what happened be<strong>for</strong>e the gas chambers or<br />

killing fields of Eastern Europe – <strong>for</strong>ced population<br />

movements, imprisonment, torture, confinement in<br />

ghettos, killings and starvation – from w hat is described<br />

above as ‘ethnic cleansing’ would have been quite difficult.<br />

As late as 1941 there were, as far as is known, no<br />

documents indicating that a ‘Final Solution’ by gassing or<br />

mass shooting w as being planned. Still, according to the<br />

UN Convention, the actions of the Nazis even prior to<br />

1941 could be regarded as genocide.<br />

In conclusion, if there is a consensus that ethnic cleansing<br />

is taking place, it means that genocide couldwell be taking<br />

place. In fact, the 1992 UN General Assembly Resolution<br />

47/121 declared that ‘the abhorrent policy of ethnic<br />

cleansing’ is ‘a <strong>for</strong>m of genocide’. 7<br />

Far from diminishing the crisis then, using the term ‘ethnic<br />

cleansing’ should be a loud alarm bell calling the w orld to<br />

take notice and take urgent action under the UN <strong>Genocide</strong><br />

Convention.<br />

1.5 Dodging the ‘g’ word<br />

In some respects, even though some consider ‘Ethnic<br />

Cleansing’ a good descriptiv e phrase <strong>for</strong> events such as<br />

those in <strong>Darfur</strong>, it seems that av oiding the word ‘genocide’<br />

lessens the gravity of the situation and reduces the<br />

pressure to act.<br />

1.5.1 Moral and political obligations<br />

One reason that there is an av oidance of using the w ord<br />

genocide is that there was a belief that once a situation<br />

was acknow ledged as genocide, there was a legal<br />

obligation to prevent. This legal obligation is not as strong<br />

as the moral and political obligation that the Convention<br />

confers. Lawyers in the US State Department have<br />

worked that out now. So unlike during the genocide in<br />

Rwanda when they av oided using the ‘g’ w ord, the US<br />

State Department is com<strong>for</strong>table being among the first to<br />

apply the word to the <strong>Darfur</strong> crisis. States also know that<br />

they can be as tardy as they like in responding to the<br />

threat of genocide, as long as they can speak strong<br />

words and demonstrate that they are doing ‘something’<br />

politically.<br />

Perhaps in the UK we are more reticent to follow this<br />

ex ample, because political leaders have made statements<br />

7 General Assembly Resolution 47/121 (1992), Preamble, Paragraph 6.<br />

3<br />

Section 1: Naming the Crisis: Policy Implications<br />

about Africa being the ‘scar on the conscience of the<br />

world’ and the political andmoral pressure to act would be<br />

heav ier ifwe recognised it as genocide.<br />

1.5.2 Devaluing the meaning ofgenocide<br />

Another argument frequently used <strong>for</strong> not being hasty to<br />

use the word ‘genocide’ is that people do not want to<br />

dev alue its meaning. Some feel that unless a catastrophe<br />

is reaching the vastness of the Holocaust in Europe in the<br />

1940s, then it is wrong to use the term genocide. But the<br />

Holocaust became vast because it was not recognised <strong>for</strong><br />

what it was and was not stopped.<br />

And so human rights organisations and politicians want to<br />

be quite certain be<strong>for</strong>e using the word. They want a<br />

crystal-clear legal definition.<br />

Being certain hinges on demonstrating that there is intent<br />

to commit genocide.<br />

1.5.3 Intent<br />

Intent, though, can be deduced from sufficient ev idence –<br />

admission of intent by the perpetrator is not necessary.<br />

The language that is used and the abundant ev idence of<br />

genocidal acts against an identified group (Africans or<br />

non-Arabs) are shown in Section 3. The systematic<br />

‘Intent can be<br />

deduced from<br />

sufficient<br />

evidence.’<br />

burning of villages coordinated with aerial bombardment<br />

ov er such a large area, the killing, the widespread rape,<br />

hav e been documented by many organisations, including<br />

the Aegis Trust. Together, this shows that there must be<br />

planning and organisation. This is especially so taking into<br />

account the v ast area of Western Sudan. It takes serious<br />

planning to coordinate air attacks with ground attacks in<br />

such an area. This could not have happened by accident.<br />

Someonemust have intended it.<br />

1.6 ‘Genocidal crisis’: a useful<br />

management term<br />

Frankly, whichev er of the above three labels – crimes<br />

against humanity, ethnic cleansing or genocide – the UN<br />

International Commission of Inquiry places on this crisis, it<br />

should not affect the management. Recognising and<br />

responding to the threat is more important.

While the point about not devaluing the meaning of the<br />

word genocide is worthy, demonstrating that there is intent<br />

happens to allow <strong>for</strong> dithering and delay in responding if<br />

genocide is happening.<br />

This is not to say that people are sitting around and<br />

waiting <strong>for</strong> the crisis to be named; but rather than a legal<br />

term on w hich it is difficult to agree, it w ould be better to<br />

hav e amanagement or descriptive term that helps to focus<br />

responses appropriately. If the label ‘ethnic cleansing’<br />

causes us to miss the point or fails to muster political will,<br />

then the term ‘genocidal crisis’ may help to convey the<br />

character of the situation.<br />

If we are com<strong>for</strong>table using the phrase ‘ethnic cleansing’ –<br />

as nearly all organisations and governments are – thenwe<br />

can call it ‘genocidal’, because this denotes that a<br />

particular group of civilians, not combatants, are the prime<br />

target. The Aegis Trust agrees with <strong>Genocide</strong> Watch and<br />

scholars such as Helen Fein that ‘ethnic cleansing’ is an<br />

unhelpful description in practice. According to the UN, it<br />

is a <strong>for</strong>m of genocide anyway (see 1.4). Sowhy not say it<br />

is genocidal? At least most of us w ho are not ex perts in<br />

international law will have a clue that the crisis is not y et<br />

another civilwar, tribalconflict or even famine. It w illmake<br />

it clear, be<strong>for</strong>e there is a consensus about the name of the<br />

crime, that someone is getting rid of a group of human<br />

beings who need protection.<br />

Applying the term ‘genocidal’ should stir a sense of<br />

urgency – because it acknowledges that genocide is<br />

threatened or may ev en be occurring. It implies the same<br />

moral and political obligations to prevent, contained in the<br />

UN <strong>Genocide</strong> Convention, as does the word ‘genocide’<br />

itself, w hile circumventing the debate necessary to achieve<br />

legal consensus on whether or not that word should be<br />

used. So when the term ‘genocidal’ is applied (e.g. in a<br />

situation currently accepted as ethnic cleansing), our<br />

response should be to act as if genocide is happening;<br />

because in all likelihood it is.<br />

Using this term ‘genocidal’ appropriately will help shape<br />

policy and management decisions in crises such as that in<br />

<strong>Darfur</strong>. The pressing task of saving lives can be<br />

addressed, and the rest left to the lawyers to resolve in<br />

their own time.<br />

The term should be applied once an assessment of risk<br />

demonstrates that a civilian population is under threat of<br />

genocide.<br />

Section 1: Naming the Crisis: Policy Implications<br />

1.7 Management implications once<br />

the term ‘genocidal’ is applied<br />

Becauseciv ilians are increasingly victims of conflict due to<br />

war crimes and other human rights abuses, great ef<strong>for</strong>t is<br />

often rightly expended to reach a political settlement<br />

betw een the conflicting sides. This brings stability and<br />

saves liv es. How ever, if a threat of genocide is<br />

recognised, it means that an identified civilian group is<br />

being targeted <strong>for</strong> destruction, possibly irrespectiv e of the<br />

armed conflict. It is possible that conflict may exacerbate,<br />

obscure or be an excuse <strong>for</strong> genocide.<br />

If there are equal sides to a conflict without genocidal<br />

signs (exclusionary ideology and systematic targeting of<br />

civilians), then security is less of an issue. If, however, a<br />

risk assessment demonstrates that there are unequal<br />

sides, that exclusionary ideology ex ists and that<br />

systematic organised violence against the target group<br />

has occurred, then this is a genocidal situation and<br />

security must be prioritised.<br />

So the key implication in calling a crisis ‘genocidal’ is that<br />

more attention should be given to the security of the<br />

vulnerable target group than would otherwise be given in a<br />

two-sided ‘conflict’ situation, where genocide is less of a<br />

risk.<br />

There are three strands to themanagement of thecrisis:<br />

1. Security<br />

2. Humanitarian aid<br />

3. Political settlement<br />

There should be no debate about whether the response<br />

should address humanitarian, political or security issues.<br />

All three must be a priority in a genocidal situation. Section<br />

4 makes it clear that of the three strands of action, security<br />

in <strong>Darfur</strong> was insufficiently prioritised by the international<br />

community. This remained the case as of November 2004.<br />

1.8 Hiding behind the humanitarian<br />

crisis<br />

During the spring and summer of 2004, the <strong>Darfur</strong> crisis<br />

was largely portrayed as a humanitarian disaster. We saw<br />

refugee camps in the news, and the main spokesperson<br />

<strong>for</strong> the UK Gov ernment was Hilary Benn, w ho w as<br />

generous and organised vast amounts of humanitarian<br />

aid. The UK quickly became the second largest donor to<br />

the aid ef<strong>for</strong>t.<br />

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) was under<br />

pressure from other member states at the UN Security<br />

4

Council who had little interest in the political issues or<br />

questions about security, no-fly zones and ending<br />

Had the crisis been recognised as ‘genocidal,’ the ef<strong>for</strong>ts<br />

to protect may have been as robust as the ef<strong>for</strong>ts to feed<br />

refugees and to achieve a political settlement.<br />

1.9 Isn’t genocide just extreme<br />

conflict?<br />

No. And the difference is v ery significant. Leav ing aside<br />

the legal definition <strong>for</strong> just a moment, we must understand<br />

that genocide is not just ex treme conflict, even though it is<br />

often associated and confusedwith conflict.<br />

5<br />

‘<strong>Genocide</strong> is more<br />

akin to extreme<br />

racism than<br />

extreme conflict.’<br />

Sections 2 and 3 of this report show ev idence of an<br />

exclusionary ideology in <strong>Darfur</strong> – racist ideas in this case.<br />

That is what differentiates genocide from a ‘conventional’<br />

two-sided conflict. If we must think about it in such nonlegal<br />

terms, then genocide is more akin to ex treme racism<br />

than ex treme conflict – it is organised, one-sided violence<br />

on a massive scale, and civ ilians, not combatants, are the<br />

prime target.<br />

1.10 But isn’t there a civil war?<br />

Against a backdrop of generations of tribal conflict, there is<br />

a civil war happening in <strong>Darfur</strong> also – since February<br />

2003. Sections 2 and 3 provide sufficient ev idence that<br />

the rebels are reacting to protect themselves from<br />

ex termination.<br />

One significant difference betw een the tw o sides is that<br />

the Janjaweed and Arab Gathering are driven by an<br />

objective to achieve exclusion of Africans. Meanwhile both<br />

rebel groups, the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM)<br />

and the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA), want to see an<br />

inclusive Sudan, such as a federal state. Such a<br />

difference is highly significant. This does not make the<br />

rebels angels; they may be angry and vengeful; they may<br />

undertake reprisals. But they are unlikely to organise<br />

genocide. It is not part of their ideology to do so. As<br />

described in Section 4, in the absence of improv ed<br />

security, it is likely that the rebels will expand their<br />

operations.<br />

Section 1: Naming the Crisis: Policy Implications<br />

impunity. It appeared convenient <strong>for</strong> the FCO to hide<br />

behindMr Benn.<br />

Summary<br />

International law allows w ide scope <strong>for</strong> prev enting<br />

genocide. There are huge moral and political<br />

obligations to do so. Resolv e and action to prev ent<br />

depend, how ever, on the politicalw ill to do so.<br />

Defining a crisis as genocide is not necessary to act.<br />

The threat of genocide – a genocidal crisis is<br />

enough. Try ing to define it may lead to delay s in<br />

action.<br />

How ev er, the pressure to act is also reduced by:<br />

• Av oiding the term genocide altogether<br />

• Keeping the v ictims distant from the<br />

conscience of the political leadership<br />

• Emphasising the tribal / civil w ar aspect of the<br />

crisis more than its genocidal nature.<br />

Section 2 demonstrates the ex istence an<br />

exclusionary ideology targetted against the Africans<br />

of <strong>Darfur</strong>. Section 3 describes how civ ilians hav e<br />

been systematically targeted.

SECTION 2<br />

<strong>Darfur</strong> and the Ideology of<br />

Sudan<br />

Contex t is critical in understanding a crisis. <strong>Genocide</strong><br />

does not happen spontaneously. It needs certain<br />

circumstances and is driven by ideology. This report<br />

cannot begin to record the complex history of Sudan. This<br />

section, however, outlines the importance of the<br />

background ideology that is a driving<br />

<strong>for</strong>ce in the current situation in<br />

Western Sudan.<br />

The Middle East and Africa conv erge<br />

in Sudan, a vast nation with a<br />

population of 39 million. Governed<br />

since independence in 1956 by three<br />

main ‘Arab’ groups who are <strong>for</strong> the<br />

most part Islamists, Sudan is<br />

fragmented by religion and ethnicity.<br />

For centuries a dy namic has played<br />

out in which many African tribes<br />

adopted not only Islam, but Arabic<br />

culture and language. Slavery has<br />

play ed a large role in shaping Sudan.<br />

African identity was regarded as<br />

being synonymous with that of a<br />

slave, leading Africans to assimilate into an Arab identity<br />

to escape the threat and stigma of slavery. Africans are<br />

still given the derogatory name ‘Abid’ meaning ‘slave’<br />

which has become a more common term in Sudan since<br />

jihad was declared in the South in 1992.<br />

This, combined with land pressure from desertification,<br />

pow er struggles, ethnic tension and Islamization have<br />

resulted in decades of strife, conflict and genocide.<br />

2.1 Arabization and Islamization<br />

Since independence, the Sudanese government has been<br />

dominated by three ‘Arab’ groups, chief among them the<br />

Jaalien, the Danagala and the Shaigia from Northern<br />

Sudan and the v arious branches of these groups. They<br />

are predominantly Islamists. Successive governments<br />

hav e sought to <strong>for</strong>m a national identity around the Arabic<br />

language, Arabic culture and Islam, and have seen this as<br />

the<br />

‘The legacy of the<br />

centuries still<br />

impacts on tribal<br />

and ethnic<br />

relations: Africans<br />

still are given the<br />

derogatory name<br />

‘Abid’ meaning<br />

‘slave.’<br />

solution to the North-South divide. 8 The implementation of<br />

the current government’s brand of Arabization and<br />

Islamization has been by far the most aggressive and<br />

sustained.<br />

The roots of the current GoS go back to the Muslim<br />

Brotherhood. This political-religious movement, was<br />

conceived in Egypt to oppose the secular constitution of<br />

Egy pt. It aimed to maintain Islamic values such as Sharia<br />

Law in the face of growing Western influence and drew<br />

heav ily from absolutist Wahhabi Islam which in<strong>for</strong>ms most<br />

Islamic terrorist groups today.<br />

Wahhabism takes a literal interpretation of the Koran and<br />

believes those who do not practice that interpretation are<br />

heathens whether they are Muslims, Christian, Jews or<br />

follow ers of any other faith. It justifies the hatred,<br />

persecution and even killing of people who do not adhere<br />

to its interpretation.<br />

The Muslim Brotherhood spread<br />

across Arab states and officially<br />

took root in Sudan in 1949<br />

although its presence had been<br />

grow ing in Sudan since the late<br />

1930s and early 1940s. The<br />

Muslim Brotherhood has been<br />

described as the ‘<strong>for</strong>efather of<br />

virtually all of today ’s Islamic terror<br />

groups, including Al Qaeda’. 9<br />

How ever, by keeping a distant<br />

relationship with such groups it<br />

was able to maintain a stance of<br />

plausible deniability over its<br />

responsibility <strong>for</strong> such actions.<br />

Hassan Al Turabi, the ideologue of<br />

the Islamist regime in Sudan throughout the 1990s, was<br />

Secretary General of the Muslim Brotherhood in late 1964.<br />

It established itself among Khartoum’s students and the<br />

higher education system, from where it was then able to<br />

infiltrate gov ernment. Since then, Turabi has acted as a<br />

pow er-broker in Sudanese politics as he has sought to<br />

achieve his goal of an Islamic state in Sudan.<br />

In 1986 Turabi <strong>for</strong>med the National Islamic Front (NIF)<br />

which staged the National Salvation Revolutionary<br />

Command coup in 1989. The aim of the NIF was to <strong>for</strong>m<br />

an Islamic state in Sudan and to fulfill Turabi’s long-stated<br />

aim to Islamize Africa.<br />

8 Johnson, D. (2003). The Root Causes of Sudan’s Civil Wars,<br />

International African Institute, London, p. 6.<br />

9 Jihad Watch, (2004). Muslim Brotherhood Activists Possibly to<br />

Return to Syria, http://www.jihadwatch.org/archives/002957.php,<br />

[Accessed 15 November 2004].<br />

6

In order to make Khartoum an Islamic centre, Turabi<br />

hosted the Pan Arab Islamic Conference (PAIC) in 1991.<br />

Ov ertly it w as a <strong>for</strong>um <strong>for</strong> Arab nationalists and Islamic<br />

organisations. The leaders of many terrorist groups in the<br />

Arabw orldw ere among the delegates at its first meeting in<br />

1991. However, secular terrorist groups did not attend<br />

subsequent conferences. It w as evident during the first<br />

conference that this was a <strong>for</strong>um controlled by Islamic<br />

fundamentalists.<br />

Attempts to draw towards the Arab world and tow ards an<br />

Arab identity have been a strong feature of the current<br />

gov ernment and society in Northern Sudan which have<br />

gone hand in hand with Islamization. Being able to claim a<br />

direct bloodline to Mohammed the prophet is regarded by<br />

many as making one a superior Muslim. It is necessary to<br />

speak Arabic in order to read the Koran.<br />

The combination of the desire of those in the North to<br />

relinquish their African identity , the religious justification <strong>for</strong><br />

the notion of the racial superiority of Arabs and<br />

Wahhabism have been potent ingredients <strong>for</strong> the<br />

dev elopment of an exclusionary ideology in Sudan.<br />

Arabization and Islamization have <strong>for</strong>med the tw o strands<br />

of the ideology of the GoSwhich it has applied through its<br />

‘Civilization Programme’. Responsibility <strong>for</strong> the realisation<br />

of this ideology lay with the Ministry of Social Planning, led<br />

in the early 1990s by Ali Uthman Muhammad Taha, onetime<br />

underling of Turabi, a hardliner and now vice<br />

president and ideologue of the Government follow ing<br />

Turabi’s split with Bashir (1999).<br />

Promotion of Arabic culture by such means as the 1992<br />

General Education Act, which made Arabic and Islamic<br />

education compulsory, was a key element of Arabization<br />

and Islamization. Arabic replaced English as the official<br />

language of government and Friday was made the weekly<br />

holiday.<br />

The creation of the Popular Defence Force (PDF) as a<br />

military <strong>for</strong>ce indoctrinated with the gov ernment ideology<br />

prov ided a means of punishing those who resisted the<br />

Islamization programme. The PDF was also regarded by<br />

the gov ernment as a vehicle <strong>for</strong> ‘national and spiritual<br />

education’. It w as modelled on the Revolutionary Guards<br />

of Iran, created by conservative clerics to guard the 1979<br />

Iranian Islamic revolt from domestic and <strong>for</strong>eign enemies.<br />

By 1994/5 all males betw een 18 and 30years of age were<br />

liable <strong>for</strong> recruitment.<br />

Yet a combined policy of Arabization and Islamization is<br />

ultimately contradictory. Whilst most Arabs are Muslim, all<br />

Muslims are by no means Arab. In Sudan, Arabs have<br />

seen themselv es as true Muslims and non-Arab Muslims<br />

7<br />

Section 2: <strong>Darfur</strong> and the Ideology of Sudan<br />

as both inferior Muslims and inferior beings. The outcome<br />

of this contradiction can be seen in <strong>Darfur</strong>, where<br />

Islamization has giv en w ay to Arabization and would-be<br />

supporters of the Islamization project have been excluded<br />

because of the additional ethnic dimension in Khartoum’s<br />

policy.<br />

Furthermore, <strong>Darfur</strong> has been neglected by Khartoum in<br />

terms of the resources allocated to it, both by the current<br />

gov ernment and those preceding it. This has led to the<br />

dev elopment of a political schism betw een the ruling<br />

northern Arab groups and the population of <strong>Darfur</strong> (both<br />

Arab and non-Arab) despite a common faith.<br />

2.2 Precedents of genocidal acts in<br />

Sudan<br />

In 1991 the Government introduced a penal code which<br />

included a law against apostacy. The Government used its<br />

vague definition of Apostacy in Article 126 of the Penal<br />

Code to legalise the annihilation of populations they<br />

regarded as obstructing their radical Islamization agenda.<br />

True to its Wahhabi roots, indigenous <strong>for</strong>ms of Islam were<br />

rejected and those adhering to these <strong>for</strong>ms of Islam were<br />

labelled apostates by the Government. The law against<br />

Apostacy was used to justify the declaration of jihad in the<br />

South in 1992. This ex emplifies the outw orking of an<br />

exclusionary ideology.<br />

The civil war in the South began follow ing President<br />

Nimairi’s division of the South into three administrative<br />

units and was inflamed by the introduction of Sharia Law,<br />

to w hich all Sudanese were subject. Beyond Sharia Law<br />

the underdev elopment of peripheral areas was also highly<br />

significant. However, the imposition of Islam has injected<br />

an ex tremely bitter element into the w ar, particularly<br />

follow ing the declaration of jihad by the NIF government in<br />

1992. Although a peace deal was signed in May 2004, the<br />

final details are currently still being teased out.<br />

Under three Islamist regimes since 1983, there have been<br />

various instances of genocide against African groups,<br />

most notably the Dinka and Nuba tribes.<br />

Helen Fein defines the actions to w hich the Dinka were<br />

subjected as ‘genocide by attrition’. 10 Between May 1983<br />

and May 1993, the Dinka were subjected to a policy of<br />

<strong>for</strong>ced starvation. Both Sadiq AlMahdi’s government, from<br />

1986 and the NIF government armed the Baggara tribe,<br />

historical enemies of the Dinka, who systematically looted<br />

the land and cattle on which they relied <strong>for</strong> survival.<br />

10 Fein, H. (1997). ‘<strong>Genocide</strong> by Attrition, 1933-1993: the Warsaw<br />

Ghetto, Cambodia and Sudan’, Health and Human Rights, 1997. Vol<br />

2, No 2. p. 10-45.

Humanitarian aid was denied. Government reactions to<br />

outbreaks of disease were to herd the displaced Dinka<br />

closer together, and medical attention was denied.<br />

Children were kidnapped and herded into camps where<br />

they were <strong>for</strong>cibly Islamized. This a clear example of the<br />

<strong>for</strong>cible transfer of children from one group to another – an<br />

action prohibited in Article 2e of the <strong>Genocide</strong><br />

Convention. 11<br />

Jihad was also declared specifically against the Nuba in<br />

Kordofan in 1992, three months after the jihad on the<br />

South. Approx imately 50% of Nuba w ere Muslim, a large<br />

proportion of the population relative to other populations in<br />

the South. The jihad was aimed as much against the<br />

Muslim population as it w as against the Christian and<br />

animist Nuba. It is evident that racism motivates these<br />

atrocities as much, if not more, than religion even though<br />

religious language was used to ‘justify ’ these atrocities.<br />

Nuba villages were terrorised and destroyed by the PDF<br />

and Arab militias leading to resettlement of 170,000 and<br />

the deaths of an estimated 100,000. 12 Like the Dinka, the<br />

Nuba were rounded up into ‘Peace Camps’ where they<br />

were confined <strong>for</strong> Islamization. The ‘Peace Camps’ were<br />

set up in hostile environments where the means <strong>for</strong><br />

survival were minimal. The land from which the Nuba were<br />

removed was sold to supporters of the regime. 13<br />

There are many similarities between the methods used<br />

against the Nuba in 1992 and the methods being used in<br />

<strong>Darfur</strong> now. The specific targeting of the male population,<br />

the raping of women and the stated intention of the<br />

Sudanese Government to create safe areas into w hich to<br />

put the internally displaced are all taking place in <strong>Darfur</strong><br />

and reflect thecrimes towhich theNubaweresubjected.<br />

2.3 A comment on ethnicity: Arabs<br />

and Africans?<br />

Some scholars understandably object to simple<br />

descriptions of ethnic relationships in Western Sudan<br />

being portray ed as Arabs against African Sudanese or<br />

non-Arabs. The authors are aware that ethnic history and<br />

relationships are often more complex. In times of peace,<br />

in particular, there is fluidity of ethnic identity including<br />

intermarriage between groups and tribes.<br />

11 Fein, H (2002). <strong>Genocide</strong> by Attrition in Sudan, Crimes of War<br />

Project, http://www.crimesofwar.org/sudan-mag/sudan-fein.html,<br />

[Accessed 12 November 2004].<br />

12 Collins, R.(2004) The Sudan<br />

http://www.gale.com/enewsletters/history/2004_08/sudan.htm<br />

[Accessed 12 November 2004].<br />

13 Johnson, D. (2003). The Root Causes of Sudan’s Civil Wars,<br />

International African Institute, London, p. 133.<br />

Section 2: <strong>Darfur</strong> and the Ideology of Sudan<br />

Many Sudanese argue that most ‘Arab’ Sudanese are<br />

black and African in origin anyway. Over the centuries<br />

tribes assumed an Arab identity – the w hole family<br />

speaking Arabic as a first language, not just the educated<br />

men. Being ‘Arab’ differentiated them from people<br />

regarded as slaves. While it may not always have been<br />

the prime reason <strong>for</strong> assuming an Arab identity, it would<br />

hav e af<strong>for</strong>ded protection from being taken into slavery<br />

themselves or from being massacred. Today hav ing an<br />

Arab identity disassociates a family from the stigma of<br />

being descended from slaves. This is ex emplified in parts<br />

of Old Khartoum where it is currently unacceptable <strong>for</strong><br />

intermarriage betw een so-called Arabs and so-called<br />

Africans. This is much more to do w ith culture and<br />

language thanskin colour.<br />

When a group is threatened, how they perceive their<br />

identity , or indeed how sociologists or anthropologists view<br />

it, becomes immaterial. What matters is how a dominant<br />

or threatening group perceives them.<br />

‘Arab’ or ‘Black African’? As a new arrival at Breidjing<br />

refugee camp, eastern Chad, this man’s identity has already<br />

been determined <strong>for</strong> him by the Janjaweed and Sudanese<br />

security <strong>for</strong>ces.<br />

An ex ample from the past: German Jews had assimilated<br />

and intermarried <strong>for</strong> several generations by the 1930s.<br />

Many perceived themselves as ‘more German than the<br />

Germans’. The Nazis did not describe them that way. It<br />

was the perpetrators’ definition that became significant.<br />

So it was <strong>for</strong> millions of others in Europe. They defined<br />

themselves in one way, possibly in a complex way, or in<br />

no w ay at all because it just w as not v ery important to<br />

them. But w hen the chips w ere down, it w as the<br />

perpetrators’ perspective that counted. Even Catholic<br />

nuns were deported to Auschw itz and gassed when they<br />

were found to have a Jewish parent or grandparent.<br />

To the perpetrators of genocide, identity is very important.<br />

They simplify it, augment it and create an ‘enemy ’. The<br />

8

Nazis made the word ‘Jew’ more prominent and negative;<br />

Hutu radicals did the same to the concept of ‘Tutsi’.<br />

Perpetrators can even invent an identity. Whatever was<br />

an ‘Aryan’? We do not understand this totally my thical<br />

race today, but <strong>for</strong> a time it was a very real identity <strong>for</strong><br />

millions of Europeans, and still is <strong>for</strong> a few. Now ‘Arab’<br />

supremacists, out of a different historical context again,<br />

are defining the Sudanese Africans, increasingly using the<br />

term ‘Zurga’ (‘nigger’) and ‘Abid’ (‘slave’). The<br />

discrimination and stereoty ping has been around <strong>for</strong><br />

centuries, but is now used to identify , exclude and destroy<br />

an ‘enemy ’.<br />

9<br />

‘To perpetrators<br />

of genocide,<br />

identity is<br />

important.’<br />

How citizens and governments view national identity is<br />

critical to the wellbeing of a nation. It may be argued,<br />

then, that the key lesson from this is that w e should not<br />

simplify the situation ourselves. It is true that we must<br />

guard against stereotypes and generalisation; we must<br />

striv e <strong>for</strong> individual responsibility rather than collective<br />

blame. We must promote inclusion, not exclusion.<br />

Exclusion is the first step to genocide.<br />

Let us not delude ourselves though. These are good<br />

principles <strong>for</strong> nation-building and community cohesion.<br />

But if people are being killed or driven out of their lands<br />

into a wilderness, we need to understand something of the<br />

mentality of the perpetrators and how they define the<br />

victim. What matters most in understanding this crisis, is<br />

that some people perceive themselves as Arab and<br />

superior, and they victimise another group because they<br />

identify them as non-Arab or African. In <strong>Darfur</strong> we have to<br />

use the perpetrators’ definition of Africans to identify w ho<br />

is under threat.<br />

It is true that there is a complex background to this<br />

situation. Tribal tensions and civil war play a part. Land<br />

ow nership and poverty are factors. But it is not good<br />

enough to blame it on ancient tribal wars, not when a<br />

Gov ernment is involved. It is not good enough to blame it<br />

on a pow er struggle or a civil w ar. That is where the<br />

simplification lies.<br />

The Aegis Trust was told over and ov er again by refugees<br />

in Chad that they w ere v ictims because the Janjaweed<br />

said they were African, or slav es (See section 4.2.2). The<br />

conflict is driven by racism at both regional and central<br />

Section 2: <strong>Darfur</strong> and the Ideology of Sudan<br />

Gov ernment level. Attempts to shroud that will undermine<br />

the resolution of thecrisis.<br />

2.4 The significance of exclusionary<br />

ideology<br />

Ideologues do not necessarily set out to find a w ay to<br />

destroy a group of people. They set out on a utopian<br />

mission. If a group is in the w ay of that mission, ways<br />

may be found to marginalise, exclude and dehumanise it.<br />

Such ideas can justify , in the mind of a dominant group,<br />

ex treme measures that can be taken against the<br />

perceiv ed inferior group. In ex treme situations a racist or<br />

exclusionary ideology sets the scene <strong>for</strong> future genocide.<br />

The National Islamic Front sought to create an Islamic<br />

state in Sudan – its Civilization Programme has sought to<br />

return to 7th-century Islam and create an Islamic paradise.<br />

An exclusionary ideology is a belief system that identifies<br />

some overriding purpose or principle that justifies ef<strong>for</strong>ts to<br />

restrict, persecute or eliminate certain categories of<br />

people. Episodes of genocide and politicide become more<br />

likely when the leaders of regimes articulate an<br />

exclusionary ideology. 14 By looking at underlying ideology<br />

we can help differentiate a possible cause of organised<br />

violence. It is an important factor in a genocidal risk<br />

assessment.<br />

‘Exclusionary<br />

ideology is the<br />

first step to<br />

genocide.’<br />

The presence of an exclusionary ideology in a time of<br />

crisis can help to differentiate the threat of genocide from<br />

other <strong>for</strong>ms of conflict.<br />

2.5 Exclusionary ideology in <strong>Darfur</strong><br />

2.5.1 Arab Congressbackground<br />

Whilst the notion of African inferiority has been a feature in<br />

Sudanese society <strong>for</strong> centuries, the emergence of an Arab<br />

supremacist ideology in <strong>Darfur</strong> coincides with the ef<strong>for</strong>ts of<br />

Liby a’s Colonel Gaddafi to create an Arab belt across<br />

14 Harff, B. (2003). “ No Lessons Learned from the Holocaust?<br />

Assessing Risks of <strong>Genocide</strong> and Political Mass Murder Since<br />

1955” , American Political Science Review, Vol 97, No. 1, pp. 57-73.

Africa, and to the mov ement of Arab militias, originally sent<br />

from Libya to fight inChad, who fled into <strong>Darfur</strong>.<br />

At this time an Arab supremacist ideology in <strong>Darfur</strong><br />

emerged, espoused by the Arab Congress, which<br />

marginalises and dehumanises Africans. 15<br />

Ev idence suggests that the Arab Congress was covertly<br />

active as early as 1980/1. At this time cassette recordings<br />

calling the Arabs in <strong>Darfur</strong> to prepare themselves to take<br />

ov er the then regional Gov ernment were w idely<br />

distributed. Having classified the citizens of <strong>Darfur</strong> as<br />

either Arabs or ‘Zurga’ Blacks, the speakers told listeners<br />

that the Zurga had had enough time ruling <strong>Darfur</strong> and that<br />

it w as time <strong>for</strong> the Arabs to take power in the region. They<br />

also demanded that the name of the region should be<br />

changed from <strong>Darfur</strong>, meaning land of the Fur, to<br />

something more suitable. Soon after the distribution of<br />

these tapes in 1982, the first massacre of Fur took place in<br />

Aw alvillage in <strong>Darfur</strong>. 16<br />

In 1980 the Nimairi Gov ernment broke with tradition in<br />

<strong>Darfur</strong> by appointing a governor to <strong>Darfur</strong> w ho w as not<br />

nativ e to the region, an Arab from Kordofan. There was<br />

considerable public protest, w hich <strong>for</strong>ced the Gov ernment<br />

to replace the governorwith Ahmed Diraige, a nativ eFur.<br />

2.5.2 Arab Congressletter to the Prime Minister: 1987<br />

The proponents of this ideology of Arab supremacy openly<br />

emerged in October 1987 in a letter sent to the Sudanese<br />

Prime Minister, Sadiq al-Mahdi, attributing to the ‘Arab<br />

race’ the ‘creation of civilisation in this region … in the<br />

areas of governance, religion and language’.<br />

The letter w as distributed widely in <strong>Darfur</strong> and Khartoum.<br />

Its tone w as supremacist and drew upon the stereoty pe<br />

popular among Arabs of Africans as being of low cultural<br />

status.<br />

The salient points of the 1987 letter to the Prime Minister<br />

are as follows:<br />

1. The Arabic tribes have been present in <strong>Darfur</strong><br />

since the 15 th Century. They represent a coherent<br />

and well defined group in spite of the fact that they<br />

are organized into various tribes. The Arabs<br />

represent about 70% of the population of <strong>Darfur</strong><br />

and about 40% of the educated <strong>Darfur</strong>ians. They<br />

are responsible <strong>for</strong> 90% of <strong>Darfur</strong>’s gross income<br />

and 15% of Sudan’s GDP. The Arabic tribe of<br />

<strong>Darfur</strong> had 14 MPs in the Parliament of Khartoum.<br />

15 The Arab Congress is also referred to as the A rab Gathering,<br />

Arabic Gathering, Quraish & Gureish.<br />

16 Ferseldin, A. (2004). “ Devils in Disguise” (unpublished essay).<br />

Section 2: <strong>Darfur</strong> and the Ideology of Sudan<br />

2. For all these reasons, the ‘Arab Gathering’<br />

requested, in their letter to the Prime Minister, to be<br />

represented by at least 50% of all constitutional<br />

posts in the regional Government of <strong>Darfur</strong> and a<br />

similar percentage in the central Government in<br />

Khartoum. The ‘Arab Gathering’ warned against<br />

ignoring the predominant Arab tribes. To ignore<br />

them would lead to dire consequences <strong>for</strong> <strong>Darfur</strong>,<br />

the letter concluded. 17<br />

A translation of the full letter can be found in Appendix D.<br />

The signatories to this letter w ere leaders of a number of<br />

Arab tribes in <strong>Darfur</strong> who called themselves the Arab<br />

Gathering. Their names are listed below:<br />

1. Ahdallah Ali Masar<br />

2. Sharif Ali Hagar<br />

3. Ibrahim Yagoub<br />

4. Hussein Hassan El Bash<br />

5. Hamid Bito<br />

6. Taj Al din Ahmed El Hilo<br />

7. Ayoub Balola<br />

8. Mohamed Khof El Fadi<br />

9. El Nazir El Hadi Eisa Dabka<br />

10. El Tayeb Abu Shama<br />

11. Sindka Dawood<br />

12. Haroun Ali El Sanousi<br />

13. Suliman-Abkr<br />

14. El Nazir Mohamed Yagoub<br />

15. Zakria Ibrahaim<br />

16. Mohamed Zakria Daldoum<br />

17. Dr. Omer Abdelgabar<br />

18. Abdullah Yahya<br />

19. Hamid Mohamed Khir Alla<br />

20. Abdel Rahman Ali<br />

21. Mohamed Shiata Ahmed<br />

22. Abu Bakr Abu Amin<br />

23. Jabir Ahmed<br />

2.5.3 Arab Congressdocuments<br />

In November 2003 a group called the Political Committee<br />

visited a number of councils in South <strong>Darfur</strong>. The Political<br />

Committee was apparently under the authority of the<br />

Coordination Council of the Arab Congress. The members<br />

of this committee w ere well known in <strong>Darfur</strong>. Some of<br />

them held important positions in the Government and<br />

National Congress. 18 The recommendations resulting from<br />

these meetings are listed below.<br />

17 This analysis was taken from a research document sourced from<br />

the <strong>Darfur</strong> Centre <strong>for</strong> Human Rights and Development,<br />

a_ismel@yahoo.co.uk, November 2004.<br />

18 Ferseldin, A. (2004). “ Devils in Disguise” (unpublished essay).<br />

10

Recommendations in the November 2003 reportof the<br />

‘Political Committee’ 19<br />

11<br />

1. The ‘idea’ 20 should be carried on with strength to<br />

achieve the results.<br />

2. To put an end to intertribal conflicts among the<br />

Arabs and to achieve unity<br />

3. Take the ‘idea’ in the context of religion, Sharia<br />

and the general Islamic principals<br />

4. To change the name of <strong>Darfur</strong> with another<br />

‘suitable’ one<br />

5. Importance and necessity <strong>for</strong> the extended<br />

presence in the Republic of Chad<br />

6. Opening up of transhumance corridors and<br />

resting places<br />

7. Strengthening of the good relations with the<br />

central Government<br />

8. Reparation of interclanal defense plan<br />

9. To bring together all Arab leaders to adopt and<br />

implement the ‘idea’<br />

10. Urge Nazir Madibbo (of Rizeigat ad Dein) and the<br />

leaders of his region to reconsider their stance<br />

and regard the matter as being very serious<br />

11. To take steps to announce without reservations,<br />

the ‘unity’ of Arabs to public since the ‘idea’ is a<br />

noble one<br />

12. All in<strong>for</strong>mation regarding internal plans should be<br />

handled in strict secrecy, and careful study to<br />

ensure safety of actions<br />

13. To switch from defensive position to an offensive,<br />

by arguments and initiatives to refute Gossip, lies<br />

and rumours<br />

14. Removal of the Popular Police Force from the<br />

State as it gets involved in a number of violations<br />

15. Complete take-over of power in South <strong>Darfur</strong><br />

State by taking advantage of our mechanical<br />

majority<br />

16. Review with Khartoum the issue of the national<br />

service<br />

17. Encourage recruitment of clan members in the<br />

armed <strong>for</strong>ces, the police and security<br />

18. Protection of all Arab politicians, especially the<br />

members of the coordination commission and<br />

obedience of their orders without reservation<br />

19. Organise the Janjaweed to per<strong>for</strong>m benevolent<br />

activities and protection<br />

20. Review the issue of immigration to Niyala<br />

At the end of each of the four meetings:<br />

a. A coordinator <strong>for</strong> the local Council was appointed<br />

b. Secretary of the National Congress was ordered<br />

to collect signatures<br />

19 Source: <strong>Darfur</strong> Centre <strong>for</strong> Human Rights and Development,<br />

November 2004.<br />

20 It is thought that the ‘idea’ referred to in this document is a plan to<br />

create a ‘Great Western State’ (Source: <strong>Darfur</strong> Centre <strong>for</strong> Human<br />

Rights and Development).<br />

Section 2: <strong>Darfur</strong> and the Ideology of Sudan<br />

c. The commissioner of the local council was to<br />

assist the secretary of the congress in collecting<br />

the signatories and to provide transport <strong>for</strong> the<br />

members of the consultative commission to<br />

Niyala as and when they demanded.<br />

2.5.4 Comment on recommendations of the Political<br />

Committee<br />

By referring to the unity of Arabs rather than that of the<br />

Sudanese, this document giv es evidence of an<br />

exclusionary ideology. Like the 1987 letter, this document<br />

alsocalls <strong>for</strong> the re-naming of <strong>Darfur</strong>.<br />

The command in point 19 concerns organizing the<br />

Janjaweed. This indicates a direct link between the<br />

Janjaweed and the Arab Gathering. Point 20b<br />

demonstrates a working relationship between the National<br />

Congress and the Arab Gathering.<br />

2.5.5 The relationship between the Arab Congress<br />

and theNational Congress Party<br />

There are strong similarities between Arab Congress<br />

statements and the Arabization policies of theNIF.<br />

In an undated, anonymous, confidential report entitled<br />

‘The Islamic Movement and the Fur Tribe’ w hich was<br />

widely circulated both inside and outside <strong>Darfur</strong>, the<br />

policies of the NIF on the Fur tribe were laid out. It first<br />

noted the contribution of the Fur to the spread of Islam in<br />

the region but then highlighted the negligible contribution<br />

the Fur have made to the current Islamic Movement. The<br />