Analytic Culture in the U.S. Intelligence Community (PDF) - CIA

Analytic Culture in the U.S. Intelligence Community (PDF) - CIA

Analytic Culture in the U.S. Intelligence Community (PDF) - CIA

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

All statements of fact, op<strong>in</strong>ion, or analysis expressed <strong>in</strong> this book<br />

are those of <strong>the</strong> authors. They do not necessarily reflect official<br />

positions of <strong>the</strong> Central <strong>Intelligence</strong> Agency or any o<strong>the</strong>r US government<br />

entity, past or present. Noth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> contents should be<br />

construed as assert<strong>in</strong>g or imply<strong>in</strong>g US government endorsement<br />

of <strong>the</strong> authors’ factual statements and <strong>in</strong>terpretations.<br />

The Center for <strong>the</strong> Study of <strong>Intelligence</strong><br />

The Center for <strong>the</strong> Study of <strong>Intelligence</strong> (CSI) was founded <strong>in</strong> 1974 <strong>in</strong><br />

response to Director of Central <strong>Intelligence</strong> James Schles<strong>in</strong>ger’s desire to create<br />

with<strong>in</strong> <strong>CIA</strong> an organization that could “th<strong>in</strong>k through <strong>the</strong> functions of<br />

<strong>in</strong>telligence and br<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> best <strong>in</strong>tellects available to bear on <strong>in</strong>telligence problems.”<br />

The Center, compris<strong>in</strong>g professional historians and experienced practitioners,<br />

attempts to document lessons learned from past operations, explore<br />

<strong>the</strong> needs and expectations of <strong>in</strong>telligence consumers, and stimulate serious<br />

debate on current and future <strong>in</strong>telligence challenges.<br />

To support <strong>the</strong>se activities, CSI publishes Studies <strong>in</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> and books<br />

and monographs address<strong>in</strong>g historical, operational, doctr<strong>in</strong>al, and <strong>the</strong>oretical<br />

aspects of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>telligence profession. It also adm<strong>in</strong>isters <strong>the</strong> <strong>CIA</strong> Museum<br />

and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>the</strong> Agency’s Historical <strong>Intelligence</strong> Collection.<br />

Comments and questions may be addressed to:<br />

Center for <strong>the</strong> Study of <strong>Intelligence</strong><br />

Central <strong>Intelligence</strong> Agency<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC 20505<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ted copies of this book are available to requesters outside <strong>the</strong><br />

US government from:<br />

Government Pr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g Office (GPO)<br />

Super<strong>in</strong>tendent of Documents<br />

P.O. Box 391954<br />

Pittsburgh, PA 15250-7954<br />

Phone: (202) 512-1800<br />

E-mail: orders@gpo.gov<br />

ISBN: 1-929667-13-2

ANALYTIC CULTURE IN THE US<br />

INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY

The Center for <strong>the</strong> Study of <strong>Intelligence</strong><br />

Central <strong>Intelligence</strong> Agency<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC 20505<br />

Johnston, Rob<br />

Library of Congress Catalogu<strong>in</strong>g-<strong>in</strong>-Publication data<br />

<strong>Analytic</strong> <strong>Culture</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> US <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong>: An Ethnographic Study/<br />

Dr. Rob Johnston<br />

Includes bibliographic references.<br />

ISBN 1-929667-13-2 (pbk.:alk paper)<br />

1. <strong>Intelligence</strong>—United States. 2. <strong>Intelligence</strong> analysis.<br />

3. <strong>Intelligence</strong> policy. 4. <strong>Intelligence</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Typeset <strong>in</strong> Times and Ariel.<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ted by Imag<strong>in</strong>g and Publication Support, <strong>CIA</strong>.<br />

Cover design: Imag<strong>in</strong>g and Publication Support, <strong>CIA</strong>.<br />

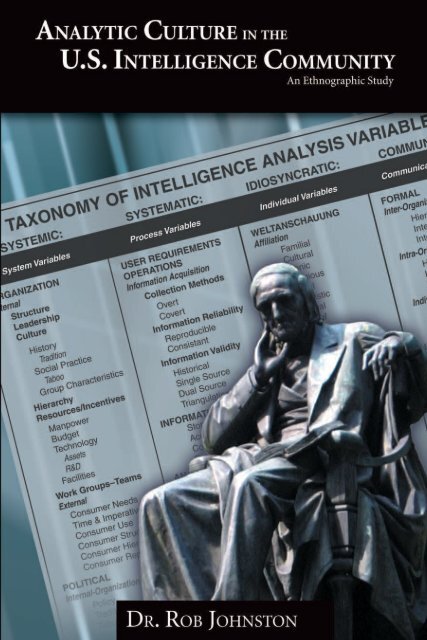

The pensive subject of <strong>the</strong> statue is Karl Ernst von Baer (1792–1876), <strong>the</strong><br />

Prussian-Estonian pioneer of embryology, geography, ethnology, and physical<br />

anthropology (Jane M. Oppenheimer, Encyclopedia Brittanica).

ANALYTIC CULTURE IN THE<br />

US INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY<br />

AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY<br />

DR. ROB JOHNSTON<br />

Center for <strong>the</strong> Study of <strong>Intelligence</strong><br />

Central <strong>Intelligence</strong> Agency<br />

Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC<br />

2005

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

There are literally slightly more than 1,000 people to thank for <strong>the</strong>ir help <strong>in</strong><br />

develop<strong>in</strong>g this work. Most of <strong>the</strong>m I cannot name, for one reason or ano<strong>the</strong>r,<br />

but my thanks go out to all of those who took <strong>the</strong> time to participate <strong>in</strong> this<br />

research project. Thank you for your trust. Particular thanks are due <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

researchers who coauthored chapters: Judith Meister Johnston, J. Dexter<br />

Fletcher, and Stephen Konya.<br />

There is a long list of <strong>in</strong>dividuals and <strong>in</strong>stitutions deserv<strong>in</strong>g of my gratitude,<br />

but, at <strong>the</strong> outset, for mak<strong>in</strong>g this study possible, I would like to express my<br />

appreciation to Paul Johnson and Woody Kuhns, <strong>the</strong> chief and deputy chief of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Central <strong>Intelligence</strong> Agency’s Center for <strong>the</strong> Study of <strong>Intelligence</strong>, and<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir staff for <strong>the</strong>ir support and to John Phillips and Tom Kennedy of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong><br />

Technology Innovation Center who, along with <strong>the</strong>ir staff, adm<strong>in</strong>ister<br />

<strong>the</strong> Director of Central <strong>Intelligence</strong> Postdoctoral Fellowship Program.<br />

I would like to thank Greg Treverton and Joe Hayes for <strong>the</strong>ir help throughout<br />

this project and for <strong>the</strong>ir will<strong>in</strong>gness to give of <strong>the</strong>ir time. Dr. Forrest<br />

Frank, Charles Perrow, and Mat<strong>the</strong>w Johnson deserve recognition for <strong>the</strong><br />

material <strong>the</strong>y contributed. Although it was not possible to cite <strong>the</strong>m as references<br />

for those contributions, <strong>the</strong>se are <strong>in</strong>dicated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> footnotes, and I give<br />

<strong>the</strong>m full credit for <strong>the</strong>ir work and efforts.<br />

I would also like to thank Bruce Berkowitz, Mike Warner, Fritz Ermarth,<br />

Gordon Oehler, Jeffrey Cooper, Dave Kaplan, John Morrison, James Wirtz,<br />

Robyn Dawes, Chris Johnson, Marilyn Peterson, Drew Cukor, Dennis<br />

McBride, Paul Chatelier, Stephen Marr<strong>in</strong>, Randy Good, Brian Hear<strong>in</strong>g, Phil<br />

Williams, Jonathan Clemente, Jim Wilson, Dennis, Kowal, Randy Murch,<br />

Gordie Boezer, Steve Holder, Joel Resnick, Mark Stout, Mike Vlahos, Mike<br />

Rigdon, Jim Silk, Karl Lowe, Kev<strong>in</strong> O’Connell, Dennis Gormley, Randy<br />

Pherson, Chris Andrew, Daniel Serfaty, Tom Armour, Gary Kle<strong>in</strong>, Brian<br />

Moon, Richard Hackman, Charlie Kisner, Matt McKnight, Joe Rosen, Mike<br />

Yared, Jen Lucas, Dick Heuer, Robert Jervis, Pam Harbourne, Katie Dorr,<br />

v

Dori Akerman, and, most particularly, my editors: Mike Schneider, Andy<br />

Vaart, and Barbara Pace. Special thanks are also due Adm. Dennis Blair, USN<br />

(Ret.), and Gen. Larry Welch, USAF (Ret.), and <strong>the</strong>ir staff.<br />

There were 50 peer reviewers who made sure I did not go too far afield <strong>in</strong><br />

my research and analysis. Aga<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong>re are mitigat<strong>in</strong>g reasons why I cannot<br />

thank <strong>the</strong>m by name. Suffice it to say, <strong>the</strong>ir work and <strong>the</strong>ir time were <strong>in</strong>valuable,<br />

and I appreciate <strong>the</strong>ir efforts.<br />

Because I cannot name specific <strong>in</strong>dividuals, I would like to thank <strong>the</strong> organizations<br />

of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> that gave me access to perform this research<br />

and made available research participants: Air Force <strong>Intelligence</strong>; Army <strong>Intelligence</strong>;<br />

Central <strong>Intelligence</strong> Agency; Defense <strong>Intelligence</strong> Agency; Department of<br />

Energy; Department of Homeland Security; Bureau of <strong>Intelligence</strong> and Research,<br />

Department of State; Department of <strong>the</strong> Treasury; Federal Bureau of Investigation;<br />

Mar<strong>in</strong>e Corps <strong>Intelligence</strong>; National Geospatial <strong>Intelligence</strong> Agency;<br />

National Reconnaissance Office; National Security Agency; Navy <strong>Intelligence</strong>.<br />

Thanks are also due <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g: Institute for Defense Analyses; <strong>the</strong> Sherman<br />

Kent Center and <strong>the</strong> Global Futures Partnership at <strong>the</strong> <strong>CIA</strong> University; <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>CIA</strong>’s Publications Review Board; Office of Public Affairs, National Archives;<br />

Jo<strong>in</strong>t Military <strong>Intelligence</strong> College; Advanced Research and Development Activity,<br />

Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA); International Association<br />

of Law Enforcement <strong>Intelligence</strong> Analysts; Drug Enforcement<br />

Adm<strong>in</strong>istration and <strong>the</strong> DEA Academy; FBI Academy; National Military <strong>Intelligence</strong><br />

Association; Association of Former <strong>Intelligence</strong> Officers; MITRE; RAND;<br />

<strong>Analytic</strong> Services, Inc. (ANSER); Potomac Institute; Center for Strategic and<br />

International Studies; Woodrow Wilson International Center; Booz Allen Hamilton;<br />

Naval Postgraduate School; Columbia University; Dartmouth College; University<br />

of Pittsburgh; Georgetown University; Carnegie Mellon University;<br />

Cambridge University; Johns Hopk<strong>in</strong>s University and <strong>the</strong> Advanced Physics<br />

Laboratory; George Mason University; Harvard University; Yale University;<br />

American Anthropological Association; Society for <strong>the</strong> Anthropology of Work;<br />

Society for Applied Anthropology; National Association for <strong>the</strong> Practice of<br />

Anthropology; Inter-University Sem<strong>in</strong>ar on Armed Forces and Society; Royal<br />

Anthropological Institute, and <strong>the</strong> national laboratories.<br />

I express my s<strong>in</strong>cere apologies if I have failed to <strong>in</strong>clude any <strong>in</strong>dividuals or<br />

organizations to which thanks are due. Moreover, any errors of commission or<br />

omission are my own. God knows, with this much help, <strong>the</strong>re is no one to<br />

blame but myself. Mostly, though, I would like to thank my long-suffer<strong>in</strong>g<br />

wife, to whom this book is dedicated. Thanks, Jude.<br />

vi

CONTENTS<br />

Foreword by Gregory F. Treverton ........................................................... xi<br />

Introduction ............................................................................................. xiii<br />

Background ...................................................................................... xiv<br />

Scope ............................................................................................... xvii<br />

A Work <strong>in</strong> Progress .......................................................................... xix<br />

Part I: Research F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

Chapter One: Def<strong>in</strong>itions ........................................................................... 3<br />

Chapter Two: F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs................................................................................ 9<br />

The Problem of Bias ........................................................................ 10<br />

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g: Secrecy Versus Efficacy ..................................................... 11<br />

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g: Time Constra<strong>in</strong>ts ................................................................ 13<br />

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g: Focus on Current Production .............................................. 15<br />

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g: Rewards and Incentives ...................................................... 16<br />

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g: “Tradecraft” Versus Scientific Methodology ..................... 17<br />

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g: Confirmation Bias, Norms, and Taboos ............................ 21<br />

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g: <strong>Analytic</strong> Identity ................................................................ 25<br />

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g: <strong>Analytic</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ............................................................... 28<br />

Part II: Ethnography of Analysis<br />

Chapter Three: A Taxonomy of <strong>Intelligence</strong> Variables ........................... 33<br />

<strong>Intelligence</strong> Analysis ......................................................................... 34<br />

Develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Taxonomy ................................................................ 37<br />

Systemic Variables ........................................................................... 39<br />

Systematic Variables ......................................................................... 40<br />

Idiosyncratic Variables ..................................................................... 41<br />

Communicative Variables ................................................................. 42<br />

Conclusion ........................................................................................ 43<br />

Chapter Four: Test<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> Cycle<br />

Through Systems Model<strong>in</strong>g and Simulation ......................................... 45<br />

The Traditional <strong>Intelligence</strong> Cycle ................................................... 45<br />

Systematic Analysis .......................................................................... 47<br />

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs Based on Systematic Analysis ........................................... 47<br />

Systemic Analysis ............................................................................. 50<br />

vii

F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs Based on Systems Analysis ................................................54<br />

Recommendations ............................................................................55<br />

Part III: Potential Areas for Improvement<br />

Chapter Five: Integrat<strong>in</strong>g Methodologists <strong>in</strong>to Teams of Experts ............61<br />

Becom<strong>in</strong>g an Expert .........................................................................61<br />

The Power of Expertise .....................................................................63<br />

The Paradox of Expertise ..................................................................64<br />

The Burden on <strong>Intelligence</strong> Analysts ................................................66<br />

The Pros and Cons of Teams .............................................................68<br />

Can Technology Help? ......................................................................71<br />

<strong>Analytic</strong> Methodologists ...................................................................72<br />

Conclusion ........................................................................................72<br />

Chapter Six: The Question of Foreign <strong>Culture</strong>s:<br />

Combat<strong>in</strong>g Ethnocentrism <strong>in</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> Analysis ...............................75<br />

Case Study One: Tiananmen Square .................................................76<br />

Case Study Two: The Red Team ......................................................81<br />

Conclusion and Recommendations ...................................................84<br />

Chapter Seven: Instructional Technology:<br />

Effectiveness and Implications for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> ...........87<br />

Background ........................................................................................88<br />

Meta-analysis Demonstrates <strong>the</strong> Effectiveness of<br />

Instructional Technology ............................................................90<br />

Current Research on Higher Cognitive Abilities ...............................92<br />

Discussion ..........................................................................................94<br />

Conclusion .........................................................................................96<br />

Chapter Eight: Organizational <strong>Culture</strong>:<br />

Anticipatory Socialization and <strong>Intelligence</strong> Analysts ............................97<br />

Organizational Socialization .............................................................98<br />

Anticipatory Socialization ................................................................99<br />

Consequences of <strong>Culture</strong> Mismatch ................................................101<br />

Anticipatory Socialization <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> .............102<br />

Conclusion and Recommendations .................................................104<br />

Chapter N<strong>in</strong>e: Recommendations ...........................................................107<br />

The First Step: Recogniz<strong>in</strong>g A Fundamental Problem ....................107<br />

Performance Improvement Infrastructure .......................................108<br />

Infrastructure Requirements ............................................................108<br />

Research Programs ..........................................................................111<br />

The Importance of Access ...............................................................115<br />

viii

Part IV: Notes on Methodology<br />

Chapter Ten: Survey Methodology ........................................................ 119<br />

Methodology ................................................................................... 120<br />

Demographics ................................................................................. 124<br />

Chapter Eleven: Q-Sort Methodology ................................................... 127<br />

Chapter Twelve: The “File-Drawer” Problem and<br />

Calculation of Effect Size .................................................................... 129<br />

Appendix: Selected Literature ............................................................... 133<br />

<strong>Intelligence</strong> Tools and Techniques ................................................. 133<br />

Cognitive Processes and <strong>Intelligence</strong> ............................................. 134<br />

Tools and Techniques as Cognitive Processes ............................... 134<br />

<strong>Intelligence</strong> Analysis as Individual Cognitive Process ................... 135<br />

Error ................................................................................................ 135<br />

Language and Cognition ................................................................. 136<br />

Bibliography............................................................................................ 139<br />

Published Sources ........................................................................... 139<br />

Web resources ................................................................................. 157<br />

Afterword by Joseph Hayes ................................................................... 159<br />

The Author .............................................................................................. 161<br />

ix

FOREWORD<br />

Gregory F. Treverton<br />

It is a rare season when <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>telligence story <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> news concerns <strong>in</strong>telligence<br />

analysis, not secret operations abroad. The United States is hav<strong>in</strong>g such<br />

a season as it debates whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>telligence failed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> run-up to both September<br />

11 and <strong>the</strong> second Iraq war, and so Rob Johnston’s wonderful book is perfectly<br />

timed to provide <strong>the</strong> back-story to those headl<strong>in</strong>es. The <strong>CIA</strong>’s Center<br />

for <strong>the</strong> Study of <strong>Intelligence</strong> is to be commended for hav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> good sense to<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d Johnston and <strong>the</strong> courage to support his work, even though his conclusions<br />

are not what many <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world of <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis would like to<br />

hear.<br />

He reaches those conclusions through <strong>the</strong> careful procedures of an anthropologist—conduct<strong>in</strong>g<br />

literally hundreds of <strong>in</strong>terviews and observ<strong>in</strong>g and participat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> dozens of work groups <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis—and so <strong>the</strong>y<br />

cannot easily be dismissed as mere op<strong>in</strong>ion, still less as <strong>the</strong> bitter mutter<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

of those who have lost out <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bureaucratic wars. His f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs constitute not<br />

just a strong <strong>in</strong>dictment of <strong>the</strong> way American <strong>in</strong>telligence performs analysis,<br />

but also, and happily, a guide for how to do better.<br />

Johnston f<strong>in</strong>ds no basel<strong>in</strong>e standard analytic method. Instead, <strong>the</strong> most common<br />

practice is to conduct limited bra<strong>in</strong>storm<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> basis of previous analysis,<br />

thus produc<strong>in</strong>g a bias toward confirm<strong>in</strong>g earlier views. The validat<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

data is questionable—for <strong>in</strong>stance, <strong>the</strong> Directorate of Operation’s (DO) “clean<strong>in</strong>g”<br />

of spy reports doesn’t permit test<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong>ir validity—re<strong>in</strong>forc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> tendency<br />

to look for data that confirms, not refutes, prevail<strong>in</strong>g hypo<strong>the</strong>ses. The<br />

process is risk averse, with considerable managerial conservatism. There is<br />

much more emphasis on avoid<strong>in</strong>g error than on imag<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g surprises. The analytic<br />

process is driven by current <strong>in</strong>telligence, especially <strong>the</strong> <strong>CIA</strong>’s crown jewel<br />

analytic product, <strong>the</strong> President’s Daily Brief (PDB), which might be caricatured<br />

xi

as “CNN plus secrets.” Johnston doesn’t put it quite that way, but <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong><br />

<strong>Community</strong> does more report<strong>in</strong>g than <strong>in</strong>-depth analysis.<br />

None of <strong>the</strong> analytic agencies knows much about <strong>the</strong> analytic techniques of<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs. In all, <strong>the</strong>re tends to be much more emphasis on writ<strong>in</strong>g and communication<br />

skills than on analytic methods. Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is driven more by <strong>the</strong><br />

dru<strong>the</strong>rs of <strong>in</strong>dividual analysts than by any strategic view of <strong>the</strong> agencies and<br />

what <strong>the</strong>y need. Most tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is on-<strong>the</strong>-job.<br />

Johnston identifies <strong>the</strong> needs for analysis of at least three different types of<br />

consumers—cops, spies, and soldiers. The needs of those consumers produce<br />

at least three dist<strong>in</strong>ct types of <strong>in</strong>telligence—<strong>in</strong>vestigative or operational, strategic,<br />

and tactical.<br />

The research suggests <strong>the</strong> need for serious study of analytic methods across<br />

all three, guided by professional methodologists. Analysts should have many<br />

more opportunities to do fieldwork abroad. They should also move much<br />

more often across <strong>the</strong> agency “stovepipes” <strong>the</strong>y now <strong>in</strong>habit. These movements<br />

would give <strong>the</strong>m a richer sense for how o<strong>the</strong>r agencies do analysis.<br />

Toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> analytic agencies should aim to create “communities of practice,”<br />

with mentor<strong>in</strong>g, analytic practice groups, and various k<strong>in</strong>ds of on-l<strong>in</strong>e<br />

resources, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g forums on methods and problem solv<strong>in</strong>g. These communities<br />

would be l<strong>in</strong>ked to a central repository of lessons learned, based on<br />

after-action post-mortems and more formal reviews of strategic <strong>in</strong>telligence<br />

products. These reviews should derive lessons for <strong>in</strong>dividuals and for teams<br />

and should look at roots of errors and failures. Oral and written histories<br />

would serve as o<strong>the</strong>r sources of wherewithal for lessons. These communities<br />

could also beg<strong>in</strong> to reshape organizations, by reth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g organizational<br />

designs, develop<strong>in</strong>g more formal socialization programs, test<strong>in</strong>g group configurations<br />

for effectiveness, and do<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> same for management and leadership<br />

practices.<br />

The agenda Johnston suggests is a daunt<strong>in</strong>g one, but it f<strong>in</strong>ds echoes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

work of small, <strong>in</strong>novative groups across <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong>—groups<br />

more tolerated than sponsored by agency leaders. With <strong>the</strong> challenge workforce<br />

demographics poses for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Community</strong>—<strong>the</strong> “gray-green” age distribution,<br />

which means that large numbers of new analysts will lack mentors as old<br />

hands retire—also comes <strong>the</strong> opportunity to refashion methods and organizations<br />

for do<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis. When <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ger-po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Wash<strong>in</strong>gton<br />

subsides, and <strong>the</strong> time for serious change arrives, <strong>the</strong>re will be no better place<br />

to start than with Rob Johnston’s f<strong>in</strong>e book.<br />

xii

INTRODUCTION<br />

In August 2001, I accepted a Director of Central <strong>Intelligence</strong> postdoctoral<br />

research fellowship with <strong>the</strong> Center for <strong>the</strong> Study of <strong>Intelligence</strong> (CSI) at <strong>the</strong><br />

Central <strong>Intelligence</strong> Agency. The purpose of <strong>the</strong> fellowship, which was to<br />

beg<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> September and last for two years, was to identify and describe conditions<br />

and variables that negatively affect <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis. Dur<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

time, I was to <strong>in</strong>vestigate analytic culture, methodology, error, and failure<br />

with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g an applied anthropological methodology<br />

that would <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong>terviews (thus far, <strong>the</strong>re have been 489), direct and<br />

participant observation, and focus groups.<br />

I began work on this project four days after <strong>the</strong> attack of 11 September, and<br />

its profound effect on <strong>the</strong> professionals <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> was<br />

clearly apparent. As a whole, <strong>the</strong> people I <strong>in</strong>terviewed and observed were<br />

patriotic without pageantry or fanfare, <strong>in</strong>telligent, hard work<strong>in</strong>g, proud of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

profession, and angry. They were angry about <strong>the</strong> attack and that <strong>the</strong> militant<br />

Islamic <strong>in</strong>surgency about which <strong>the</strong>y had been warn<strong>in</strong>g policymakers for<br />

years had murdered close to 3,000 people <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States itself. There<br />

was also a sense of guilt that <strong>the</strong> attack had happened on <strong>the</strong>ir watch and that<br />

<strong>the</strong>y had not been able to stop it.<br />

Hav<strong>in</strong>g occurred under <strong>the</strong> dark shadow of that attack, this study has no<br />

comparable basel<strong>in</strong>e aga<strong>in</strong>st which its results could be tested, and it is difficult<br />

to identify biases that might exist <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se data as a result of 11 September. In<br />

some ways, post-9/11 data may be questionable. For example, angry people<br />

may have an ax to gr<strong>in</strong>d or an agenda to push and may not give <strong>the</strong> most reliable<br />

<strong>in</strong>terviews. Yet, <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r ways, post-9/11 data may be more accurate.<br />

When people become angry enough, <strong>the</strong>y tend to blurt out <strong>the</strong> truth—or, at<br />

least, <strong>the</strong>ir perception of <strong>the</strong> truth. The people I encountered were, <strong>in</strong> my judgxiii

INTRODUCTION<br />

ment, very open and honest; and this, too, may be attributable to 9/11. In any<br />

case, that event is now part of <strong>the</strong> culture of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong>, and<br />

that <strong>in</strong>cludes whatever consequences or biases resulted from it.<br />

Background<br />

The opportunity to do this research presented itself, at least <strong>in</strong> part, as a<br />

result of my participation <strong>in</strong> a multiyear research program on medical error<br />

and failure for <strong>the</strong> Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). 1<br />

The DARPA research focused on team and <strong>in</strong>dividual error <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imally <strong>in</strong>vasive<br />

or laparoscopic surgical procedures. This research revealed that <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

errors were cognitive ra<strong>the</strong>r than purely psychomotor or skill-based. For<br />

example, some surgeons had trouble navigat<strong>in</strong>g three-dimensional anatomical<br />

space us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g laparoscopic technology, with <strong>the</strong> result that <strong>the</strong>se<br />

surgeons would identify anatomical structures <strong>in</strong>correctly and perform a surgical<br />

procedure on <strong>the</strong> wrong body part.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>dividual errors were discovered dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> DARPA studies, but, for<br />

<strong>the</strong> most part, <strong>the</strong>se were spatial navigation and recognition problems for<br />

which <strong>the</strong>re were technological solutions. Team errors, unlike <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

errors, proved to be more challeng<strong>in</strong>g. The formal and <strong>in</strong>formal hierarchical<br />

structures of operat<strong>in</strong>g rooms did not lend <strong>the</strong>mselves to certa<strong>in</strong> performance<br />

<strong>in</strong>terventions. Generally, junior surgical staff and support personnel were not<br />

will<strong>in</strong>g to confront a senior staff member who was committ<strong>in</strong>g, or was about<br />

to commit, an error.<br />

The culture of <strong>the</strong> operat<strong>in</strong>g room, coupled with <strong>the</strong> social and career structure<br />

of <strong>the</strong> surgical profession, created barriers to certa<strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ds of communication.<br />

For a surgical resident to <strong>in</strong>form a senior surgeon <strong>in</strong> front of <strong>the</strong> entire<br />

operat<strong>in</strong>g room staff that he was about to cut <strong>the</strong> wrong organ could result <strong>in</strong><br />

career “suicide.” Such a confrontation could have been perceived by <strong>the</strong><br />

senior surgeon as a form of mut<strong>in</strong>y aga<strong>in</strong>st his authority and expertise and a<br />

challenge to <strong>the</strong> social order of <strong>the</strong> operat<strong>in</strong>g room. Although not universal,<br />

this taboo is much more common than surgeons would care to admit. Unlike<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual errors, purely technological solutions were of little value <strong>in</strong> try<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to solve team errors <strong>in</strong> a surgical environment.<br />

The DARPA surgical research was followed up by a multiyear study of<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual and team performance of astronauts at <strong>the</strong> National Aeronautics<br />

and Space Adm<strong>in</strong>istration’s (NASA) Johnson Space Center. Results of <strong>the</strong><br />

NASA study, also sponsored by DARPA, were similar to <strong>the</strong> surgical study<br />

1<br />

Rob Johnston, J. Dexter Fletcher and Sunil Bhoyrul, The Use of Virtual Reality to Measure Surgical<br />

Skill Levels.<br />

xiv

INTRODUCTION<br />

with regard to team <strong>in</strong>teractions. Although, on <strong>the</strong> face of it, teams of astronauts<br />

were composed of peers, a social dist<strong>in</strong>ction never<strong>the</strong>less existed<br />

between commander, pilots, and mission specialists.<br />

As with surgery, <strong>the</strong>re was a dis<strong>in</strong>centive for one team member to confront<br />

or criticize ano<strong>the</strong>r, even <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> face of an impend<strong>in</strong>g error. Eighty percent of<br />

<strong>the</strong> current astronauts come from <strong>the</strong> military, which has very specific rules<br />

regard<strong>in</strong>g confrontations, dissent, and criticism. 2 In addition to <strong>the</strong> similarities<br />

<strong>in</strong> behavior aris<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong>ir common backgrounds, <strong>the</strong> “criticism” taboo<br />

was cont<strong>in</strong>ually re<strong>in</strong>forced throughout <strong>the</strong> astronaut’s career. Virtually any<br />

negative comment on an astronaut’s record was sufficient for him or her to be<br />

assigned to ano<strong>the</strong>r crew, “washed out” of an upcom<strong>in</strong>g mission and recycled<br />

through <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g program, or, worse still, released from <strong>the</strong> space program<br />

altoge<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Taboos are social markers that prohibit specific behaviors <strong>in</strong> order to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><br />

and propagate an exist<strong>in</strong>g social structure. Generally, <strong>the</strong>y are unwritten<br />

rules not available to outside observers. Insiders, however, almost always perceive<br />

<strong>the</strong>m simply as <strong>the</strong> way th<strong>in</strong>gs are done, <strong>the</strong> natural social order of <strong>the</strong><br />

organization. To confront taboos is to confront <strong>the</strong> social structure of a culture<br />

or organization.<br />

I mention <strong>the</strong> surgical and astronautical studies for a number of reasons.<br />

Each serves as background for <strong>the</strong> study of <strong>in</strong>telligence analysts. Astronauts<br />

and surgeons have very high performance standards and low error rates. 3 Both<br />

studies highlight o<strong>the</strong>r complex doma<strong>in</strong>s that are <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

own professional performance. Both studies reveal <strong>the</strong> need to employ a variety<br />

of research methods to deal with complicated issues, and <strong>the</strong>y suggest that<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are lessons to be learned from o<strong>the</strong>r doma<strong>in</strong>s. Perhaps <strong>the</strong> most tell<strong>in</strong>g<br />

connection is that, because lives are at stake, surgeons and astronauts experience<br />

tremendous <strong>in</strong>ternal and external social pressure to avoid failure. The<br />

same often holds for <strong>in</strong>telligence analysts.<br />

In addition, surgery and astronautics are highly selective and private discipl<strong>in</strong>es.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong>ir work is not secret, both groups tend to be shielded from<br />

<strong>the</strong> outside world: surgeons for reasons of professional selection, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> fiscal realities of malpractice liability; astronauts because <strong>the</strong>ir community<br />

2<br />

National Aeronautics and Space Adm<strong>in</strong>istration, Astronaut Fact Book.<br />

3<br />

NASA has launched missions with <strong>the</strong> shuttle fleet 113 times s<strong>in</strong>ce 1981 and has experienced<br />

two catastrophic failures. It is probable that both of those were mechanical/eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g failures<br />

and not <strong>the</strong> result of astronaut error. Surgical report<strong>in</strong>g methods vary from hospital to hospital,<br />

and it is often difficult to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> specific causes of morbidity and mortality. One longitud<strong>in</strong>al<br />

study of all surgical procedures <strong>in</strong> one medical center puts <strong>the</strong> surgical error rates at that center<br />

between 2.7 percent and 7.5 percent. See Hunter McGuire, Shelton Horsley, David Salter, et al.,<br />

“Measur<strong>in</strong>g and Manag<strong>in</strong>g Quality of Surgery: Statistical vs. Incidental Approaches.”<br />

xv

INTRODUCTION<br />

is so small and <strong>the</strong> selection and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g processes are so demand<strong>in</strong>g. 4 <strong>Intelligence</strong><br />

analysts share many of <strong>the</strong>se organizational and professional circumstances.<br />

The <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> is relatively small, highly selective, and<br />

largely shielded from public view. For its practitioners, <strong>in</strong>telligence work is a<br />

cognitively-demand<strong>in</strong>g and high-risk profession that can lead to public policy<br />

that streng<strong>the</strong>ns <strong>the</strong> nation or puts it at greater risk. Because <strong>the</strong> consequences<br />

of failure are so great, <strong>in</strong>telligence professionals cont<strong>in</strong>ually feel significant<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternal and external pressure to avoid it. One consequence of this pressure is<br />

that <strong>the</strong>re has been a long-stand<strong>in</strong>g bureaucratic resistance to putt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> place a<br />

systematic program for improv<strong>in</strong>g analytical performance. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

71 percent of <strong>the</strong> people I <strong>in</strong>terviewed, however, that resistance has dim<strong>in</strong>ished<br />

significantly s<strong>in</strong>ce September 2001.<br />

It is not difficult to understand <strong>the</strong> historical resistance to implement<strong>in</strong>g<br />

such a performance improvement program. Simply put, a program explicitly<br />

designed to improve human performance implies that human performance<br />

needs improv<strong>in</strong>g, an allegation that risks considerable political and <strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

resistance. Not only does performance improvement imply that <strong>the</strong> system<br />

is not optimal, <strong>the</strong> necessary scrut<strong>in</strong>y of practice and performance would<br />

require exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g sources and methods <strong>in</strong> detail throughout <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong><br />

<strong>Community</strong>. Although this scrut<strong>in</strong>y would be wholly <strong>in</strong>ternal to <strong>the</strong> community,<br />

<strong>the</strong> concept runs counter to a culture of secrecy and compartmentalization.<br />

The conflict between secrecy, a necessary condition for <strong>in</strong>telligence, and<br />

openness, a necessary condition for performance improvement, was a recurr<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong>me I observed dur<strong>in</strong>g this research. Any organization that requires<br />

secrecy to perform its duties will struggle with and often reject openness, even<br />

at <strong>the</strong> expense of efficacy. Despite this, and to <strong>the</strong>ir credit, a number of small<br />

groups with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> have tasked <strong>the</strong>mselves with creat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

formal and <strong>in</strong>formal ties with <strong>the</strong> nation’s academic, non-profit, and <strong>in</strong>dustrial<br />

communities. In addition, <strong>the</strong>re has been an appreciable <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

use of alternative analyses and open-source materials.<br />

These efforts alone may not be sufficient to alter <strong>the</strong> historical culture of<br />

secrecy, but <strong>the</strong>y do re<strong>in</strong>force <strong>the</strong> idea that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> itself<br />

has a responsibility to reconsider <strong>the</strong> relationship between secrecy, openness,<br />

and efficacy. This is especially true as it relates to <strong>the</strong> community’s performance<br />

and <strong>the</strong> occurrence of errors and failure. External oversight and public<br />

debate will not solve <strong>the</strong>se issues; <strong>the</strong> desire to improve <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> Com-<br />

4<br />

There are currently 109 active US astronauts and 36 management astronauts. See National Aeronautics<br />

and Space Adm<strong>in</strong>istration-Johnson Space Center career astronaut biographies.<br />

xvi

INTRODUCTION<br />

munity’s performance needs to come from with<strong>in</strong>. Once <strong>the</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>ation has<br />

been found and <strong>the</strong> necessary policy guidel<strong>in</strong>es put <strong>in</strong> place, it is <strong>in</strong>cumbent<br />

upon <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> to f<strong>in</strong>d and utilize <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal and external<br />

resources necessary to create a performance improvement <strong>in</strong>frastructure.<br />

Scope<br />

This project was designed explicitly as an applied research program. In<br />

many respects, it resembles an assessment of organizational needs and a gap<br />

analysis, <strong>in</strong> that it was <strong>in</strong>tended to identify and describe conditions and variables<br />

that affect <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis and <strong>the</strong>n to identify needs, specifications,<br />

and requirements for <strong>the</strong> development of tools, techniques, and<br />

procedures to reduce analytic error. Based on <strong>the</strong>se f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs, I was to make<br />

recommendations to improve analytic performance.<br />

In previous human performance-related research conducted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> military,<br />

medical, and astronautic fields, I have found <strong>in</strong> place—especially <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> military—a<br />

large social science literature, an elaborate tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g doctr<strong>in</strong>e, and welldeveloped<br />

quantitative and qualitative research programs. In addition to<br />

research literature and programs, <strong>the</strong>se three discipl<strong>in</strong>es have substantial performance<br />

improvement programs. This was not <strong>the</strong> case with <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong><br />

<strong>Community</strong>.<br />

This is not to say that an <strong>in</strong>telligence literature does not exist but ra<strong>the</strong>r that<br />

<strong>the</strong> literature that does exist has been focused to a greater extent on case studies<br />

than on <strong>the</strong> actual process of <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis. 5 The vast majority of<br />

<strong>the</strong> available literature is about history, <strong>in</strong>ternational relations, and political<br />

science. Texts that address analytic methodology do exist, and it is worth not<strong>in</strong>g<br />

that <strong>the</strong>re are quantitative studies, such as that by Robert Folker, that compare<br />

<strong>the</strong> effectiveness of different analytic methods for solv<strong>in</strong>g a given<br />

analytic problem. Folker’s study demonstrates that objective, quantitative, and<br />

controlled research to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> effectiveness of analytic methods is possible.<br />

6<br />

The literature that deals with <strong>the</strong> process of <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis tends to be<br />

personal and idiosyncratic, reflect<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>dividualistic approach to problem<br />

solv<strong>in</strong>g. This is not surpris<strong>in</strong>g. The <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> is made up of a<br />

variety of discipl<strong>in</strong>es, each with its own analytic methodology. The organizational<br />

assumption has been that, <strong>in</strong> a multidiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary environment, <strong>in</strong>telli-<br />

5<br />

There are exceptions. See <strong>the</strong> appendix.<br />

6<br />

MSgt. Robert D. Folker, <strong>Intelligence</strong> Analysis <strong>in</strong> Theater Jo<strong>in</strong>t <strong>Intelligence</strong> Centers. Folker’s<br />

study conta<strong>in</strong>s a methodological flaw <strong>in</strong> that it does not describe one of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent variables<br />

(<strong>in</strong>tuitive method), leav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> dependent variable (test scores) <strong>in</strong> doubt.<br />

xvii

INTRODUCTION<br />

gence analysts would use analytic methods and tools from <strong>the</strong>ir own doma<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> order to analyze and solve <strong>in</strong>telligence problems. When <strong>in</strong>terdiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary<br />

problems have arisen, <strong>the</strong> organizational assumption has been that a variety of<br />

analytic methods would be employed, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a “best fit” syn<strong>the</strong>sis.<br />

This <strong>in</strong>dividualistic approach to analysis has resulted <strong>in</strong> a great variety of<br />

analytic methods—I identified at least 160 <strong>in</strong> my research for this paper—but<br />

it has not led to <strong>the</strong> development of a standardized analytic doctr<strong>in</strong>e. That is,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is no body of research across <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> assert<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

method X is <strong>the</strong> most effective method for solv<strong>in</strong>g case one and that method Y<br />

is <strong>the</strong> most effective method for solv<strong>in</strong>g case two. 7<br />

The utility of a standardized analytic doctr<strong>in</strong>e is that it enables an organization<br />

to determ<strong>in</strong>e performance requirements, a standard level of <strong>in</strong>stitutional<br />

expertise, and <strong>in</strong>dividual performance metrics for <strong>the</strong> evaluation and development<br />

of new analytic methodologies. 8 Ultimately, without such an analytic<br />

basel<strong>in</strong>e, one cannot assess <strong>the</strong> effectiveness of any new or proposed analytic<br />

method, tool, technology, reorganization, or <strong>in</strong>tervention. Without standardized<br />

analytic doctr<strong>in</strong>e, analysts are left to <strong>the</strong> ra<strong>the</strong>r slow and tedious process<br />

of trial and error throughout <strong>the</strong>ir careers.<br />

Generally, <strong>in</strong> research literature, one f<strong>in</strong>ds a taxonomy, or matrix, of <strong>the</strong><br />

variables that affect <strong>the</strong> object under study. Taxonomies help to standardize<br />

def<strong>in</strong>itions and <strong>in</strong>form future research by establish<strong>in</strong>g a research “road map.”<br />

They po<strong>in</strong>t out areas of <strong>in</strong>terest and research priorities and help researchers<br />

place <strong>the</strong>ir own research programs <strong>in</strong> context. In my search of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>telligence<br />

literature, I found no taxonomy of <strong>the</strong> variables that affect <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis.<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> literature review, I undertook to develop work<strong>in</strong>g def<strong>in</strong>itions<br />

and a taxonomy <strong>in</strong> order to systematize <strong>the</strong> research process. Readers will f<strong>in</strong>d<br />

<strong>the</strong> work<strong>in</strong>g def<strong>in</strong>itions <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first chapter. The second chapter highlights <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> broader f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs and implications of this ethnographic study. Because <strong>the</strong><br />

first two chapters conta<strong>in</strong> many quotes from my <strong>in</strong>terviews and workshops,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y illustrate <strong>the</strong> tone and nature of <strong>the</strong> post-9/11 environment <strong>in</strong> which I<br />

worked.<br />

The taxonomy that grew out of this work was first described <strong>in</strong> an article for<br />

<strong>the</strong> CSI journal, Studies <strong>in</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong>, and is presented here as Chapter<br />

7<br />

There is no s<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong> basic analytic tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g program. There is, however,<br />

community use of advanced analytic courses at both <strong>the</strong> <strong>CIA</strong> University and <strong>the</strong> Jo<strong>in</strong>t Military<br />

<strong>Intelligence</strong> College. The Generic <strong>Intelligence</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Initiative is a recent attempt to standardize<br />

certa<strong>in</strong> law enforcement <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programs through a basic law enforcement<br />

analyst tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g curriculum. The program has been developed by <strong>the</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Advisory<br />

Council, under <strong>the</strong> Counterdrug <strong>Intelligence</strong> Coord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g Group and <strong>the</strong> Justice Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Center.<br />

8<br />

See <strong>the</strong> appendix.<br />

xviii

INTRODUCTION<br />

Three. In addition to <strong>the</strong> normal journal review process, I circulated a draft of<br />

<strong>the</strong> taxonomy among 55 academics and <strong>in</strong>telligence professionals and <strong>in</strong>corporated<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir suggestions <strong>in</strong> a revised version that went to press. This is not to<br />

assert that <strong>the</strong> taxonomy is f<strong>in</strong>al; <strong>the</strong> utility of any taxonomy is that it can be<br />

revised and expanded as new research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs become available. The chapter<br />

by Dr. Judith Meister Johnston that follows offers an alternative model—more<br />

complex and possibly more accurate than <strong>the</strong> traditional <strong>in</strong>telligence cycle—<br />

for look<strong>in</strong>g at <strong>the</strong> dynamics of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>telligence process, <strong>in</strong> effect <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terrelationships<br />

of many elements of <strong>the</strong> taxonomy<br />

The follow<strong>in</strong>g chapters, prepared by me and o<strong>the</strong>r able colleagues, were<br />

developed around o<strong>the</strong>r variables <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> taxonomy and offer suggestions for<br />

improvement <strong>in</strong> those specific areas. One of <strong>the</strong>m—Chapter Five, on <strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

methodologists and substantive experts <strong>in</strong> research teams—also appeared<br />

<strong>in</strong> Studies <strong>in</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong>. Chapter N<strong>in</strong>e conta<strong>in</strong>s several broad recommendations,<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g suggestions for fur<strong>the</strong>r research.<br />

To <strong>the</strong> extent possible, I tried to avoid us<strong>in</strong>g professional jargon. Even so,<br />

<strong>the</strong> reader will still f<strong>in</strong>d a number of specific technical terms, and, <strong>in</strong> those<br />

cases, I have <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>the</strong>ir discipl<strong>in</strong>ary def<strong>in</strong>itions as footnotes.<br />

A Work <strong>in</strong> Progress<br />

In some respects, it may seem strange or unusual to have an anthropologist<br />

perform this type of work ra<strong>the</strong>r than an <strong>in</strong>dustrial/organizational psychologist<br />

or some o<strong>the</strong>r specialist <strong>in</strong> professional performance improvement or bus<strong>in</strong>ess<br />

processes. The common perception of cultural anthropology is one of fieldwork<br />

among <strong>in</strong>digenous peoples. Much has changed dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> past 40 years,<br />

however. Today, <strong>the</strong>re are many practitioners and professional associations<br />

devoted to <strong>the</strong> application of anthropology and its field methods to practical<br />

problem-solv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> modern or post<strong>in</strong>dustrial society. 9<br />

It is difficult for any modern anthropological study to escape <strong>the</strong> legacy of<br />

Margaret Mead. She looms as large over 20th century anthropology as does<br />

Sherman Kent over <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>telligence profession. Although Franz Boas is arguably<br />

<strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>r of American anthropology and was Margaret Mead’s mentor,<br />

hers is <strong>the</strong> name everyone recognizes and connects to ethnography. 10 Chances<br />

are, if one has read anthropological texts, one has read Mead.<br />

9<br />

The Society for Applied Anthropology and <strong>the</strong> National Association for <strong>the</strong> Practice of Anthropology<br />

section of <strong>the</strong> American Anthropological Association are <strong>the</strong> two pr<strong>in</strong>cipal anthropological<br />

groups. Ano<strong>the</strong>r group is <strong>the</strong> Inter-University Sem<strong>in</strong>ar on Armed Forces and Society, a<br />

professional organization represent<strong>in</strong>g 700 social science fellows, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g practic<strong>in</strong>g anthropologists,<br />

apply<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir research methods to issues <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> military.<br />

xix

INTRODUCTION<br />

I mention Mead not only because my work draws heavily on hers, but also<br />

because of her impact on <strong>the</strong> discipl<strong>in</strong>e and its direction. She moved from traditional<br />

cultural anthropological fieldwork <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> South Pacific to problemoriented<br />

applied anthropology dur<strong>in</strong>g World War II. She was <strong>the</strong> founder of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Institute for Intercultural Studies and a major contributor to <strong>the</strong> Cold War<br />

RAND series that attempted to describe <strong>the</strong> Soviet character. She also pioneered<br />

many of <strong>the</strong> research methods that are used <strong>in</strong> applied anthropology<br />

today. I mention her work also as an illustrative po<strong>in</strong>t. After two years of field<br />

research <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> South Pacific, she wrote at least five books and could possibly<br />

have written more.<br />

As I look over <strong>the</strong> stacks of documentation for this study, it occurs to me<br />

that, given <strong>the</strong> various constra<strong>in</strong>ts of <strong>the</strong> fellowship, <strong>the</strong>re is more material<br />

here than I will be able to address <strong>in</strong> any one text. There are <strong>the</strong> notes from<br />

489 <strong>in</strong>terviews, direct observations, participant observations, and focus<br />

groups; <strong>the</strong>re are personal letters, e-mail exchanges, and archival material; and<br />

<strong>the</strong>re are my own notes track<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> progress of <strong>the</strong> work. Moreover, <strong>the</strong> fieldwork<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ues. As I write this, I am schedul<strong>in</strong>g more <strong>in</strong>terviews, more observations,<br />

and yet more fieldwork.<br />

This text, <strong>the</strong>n, is more a progress report than a f<strong>in</strong>al report <strong>in</strong> any traditional<br />

sense. It reflects f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs and recommendations to date and is <strong>in</strong> no way<br />

comprehensive. F<strong>in</strong>ally, based as it is on my own research <strong>in</strong>terests and<br />

research opportunities, it is but one piece of a much larger puzzle.<br />

10<br />

Boas (1858–1942) developed <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic and cultural components of ethnology. His most<br />

notable work was Race, Language, and <strong>Culture</strong> (1940).<br />

xx

PART I<br />

Research F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

1

eth•nog•ra•phy\n [F ethnographie, fr. ethno- + -graphie -graphy] (1834) :<br />

<strong>the</strong> study and systematic record<strong>in</strong>g of human cultures: also: a descriptive work<br />

produced from such research. (Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary,<br />

Eleventh Edition)<br />

2

CHAPTER ONE<br />

Def<strong>in</strong>itions<br />

Because I conducted human performance–related fieldwork before I came<br />

to this project, I carried <strong>in</strong>to it a certa<strong>in</strong> amount of experiential bias, or “cognitive<br />

baggage.” The research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from those o<strong>the</strong>r studies could bias my<br />

perspective and research approach with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> <strong>Community</strong>. For<br />

example, surgeons and astronauts do not need to deal with <strong>in</strong>tentionally<br />

deceptive data. Patients are not try<strong>in</strong>g to “hide” <strong>the</strong>ir illnesses from surgeons,<br />

and spacecraft are not th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g adversaries <strong>in</strong>tent on deny<strong>in</strong>g astronauts critical<br />

pieces of <strong>in</strong>formation. This one difference may mean that <strong>in</strong>telligence<br />

analysis is much more cognitively challeng<strong>in</strong>g than <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r two cases and<br />

that <strong>the</strong> requisite psychomotor skills are significantly less important. In an<br />

effort to counteract <strong>the</strong> biases of experience, I will attempt to be explicit about<br />

my own def<strong>in</strong>itions <strong>in</strong> this work.<br />

Work<strong>in</strong>g Def<strong>in</strong>itions<br />

The three ma<strong>in</strong> def<strong>in</strong>itions used <strong>in</strong> this work do not necessarily represent<br />

def<strong>in</strong>itions derived from <strong>the</strong> whole of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>telligence literature. Although<br />

some of <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>itions used <strong>in</strong> this work are based on <strong>the</strong> Q-sort survey of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>telligence literature described later, some are based on <strong>the</strong> 489 <strong>in</strong>terviews,<br />

focus groups, and two years of direct and participant observations collected<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g this project.<br />

3

CHAPTER ONE<br />

Def<strong>in</strong>ition 1: <strong>Intelligence</strong> is secret state or group activity to understand<br />

or <strong>in</strong>fluence foreign or domestic entities.<br />

The above def<strong>in</strong>ition of <strong>in</strong>telligence, as used <strong>in</strong> this text, is a slightly modified<br />

version of <strong>the</strong> one that appeared <strong>in</strong> Michael Warner’s work <strong>in</strong> a recent<br />

article <strong>in</strong> Studies In <strong>Intelligence</strong>. 1 Warner reviews and syn<strong>the</strong>sizes a number<br />

of previous attempts to def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> discipl<strong>in</strong>e of <strong>in</strong>telligence and comes to <strong>the</strong><br />

conclusion that “<strong>Intelligence</strong> is secret state activity to understand or <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

foreign entities.”<br />

Warner’s syn<strong>the</strong>sis seems to focus on strategic <strong>in</strong>telligence, but it is also<br />

logically similar to actionable <strong>in</strong>telligence (both tactical and operational)<br />

designed to <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>the</strong> cognition or behavior of an adversary. 2 This syn<strong>the</strong>sis<br />

captures most of <strong>the</strong> elements of actionable <strong>in</strong>telligence without be<strong>in</strong>g too<br />

restrictive or too open-ended, and those I asked to def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> word found its<br />

elements, <strong>in</strong> one form or ano<strong>the</strong>r, to be generally acceptable. The modified<br />

version proposed here is based on Warner’s def<strong>in</strong>ition and <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terview and<br />

observation data collected among <strong>the</strong> law enforcement elements of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>telligence<br />

agencies. These elements confront adversaries who are not nation states<br />

or who may not be foreign entities. With this <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, I chose to def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>telligence<br />

somewhat more broadly, to <strong>in</strong>clude nonstate actors and domestic <strong>in</strong>telligence<br />

activities performed with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States.<br />

Def<strong>in</strong>ition 2: <strong>Intelligence</strong> analysis is <strong>the</strong> application of <strong>in</strong>dividual<br />

and collective cognitive methods to weigh data and test hypo<strong>the</strong>ses<br />

with<strong>in</strong> a secret socio-cultural context.<br />

This mean<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis was harder to establish, and readers<br />

will f<strong>in</strong>d a more comprehensive review <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g chapter on develop<strong>in</strong>g<br />

an <strong>in</strong>telligence taxonomy. In short, <strong>the</strong> literature tends to divide <strong>in</strong>telligence<br />

analysis <strong>in</strong>to “how-to” tools and techniques or cognitive processes. This is not<br />

to say that <strong>the</strong>se items are mutually exclusive; many authors see <strong>the</strong> tools and<br />

techniques of analysis as cognitive processes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>mselves and are reluctant<br />

to place <strong>the</strong>m <strong>in</strong> different categories. Some authors tend to perceive <strong>in</strong>telligence<br />

analysis as essentially an <strong>in</strong>dividual cognitive process or processes. 3<br />

My work dur<strong>in</strong>g this study conv<strong>in</strong>ced me of <strong>the</strong> importance of mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

explicit someth<strong>in</strong>g that is not well described <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature, namely, <strong>the</strong> very<br />

1<br />

Michael Warner, “Wanted: A Def<strong>in</strong>ition of ‘<strong>Intelligence</strong>’,” Studies <strong>in</strong> <strong>Intelligence</strong> 46, no. 3<br />

(2002): 15–22.<br />

2<br />

US Jo<strong>in</strong>t Forces Command, Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated<br />

Terms.<br />

3<br />

The appendix lists literature devoted to each of <strong>the</strong>se areas.<br />

4

DEFINITIONS<br />

<strong>in</strong>teractive, dynamic, and social nature of <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis. The <strong>in</strong>terview<br />

participants were not asked to def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis as such; ra<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

were asked to describe and expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> process <strong>the</strong>y used to perform analysis.<br />

The <strong>in</strong>terview data were <strong>the</strong>n triangulated with <strong>the</strong> direct and participant<br />

observation data collected dur<strong>in</strong>g this study. 4<br />

Despite <strong>the</strong> seem<strong>in</strong>gly private and psychological nature of analysis as<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature, what I found was a great deal of <strong>in</strong>formal, yet purposeful<br />

collaboration dur<strong>in</strong>g which <strong>in</strong>dividuals began to make sense of raw<br />

data by negotiat<strong>in</strong>g mean<strong>in</strong>g among <strong>the</strong> historical record, <strong>the</strong>ir peers, and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

supervisors. Here, from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terviews, is a typical description of <strong>the</strong> analytic<br />

process:<br />

When a request comes <strong>in</strong> from a consumer to answer some question,<br />

<strong>the</strong> first th<strong>in</strong>g I do is to read up on <strong>the</strong> analytic l<strong>in</strong>e. [I] check <strong>the</strong><br />

previous publications and <strong>the</strong> data. Then, I read through <strong>the</strong> question<br />

aga<strong>in</strong> and f<strong>in</strong>d where <strong>the</strong>re are l<strong>in</strong>ks to previous products.<br />

When I th<strong>in</strong>k I have an answer, I get toge<strong>the</strong>r with my group and ask<br />

<strong>the</strong>m what <strong>the</strong>y th<strong>in</strong>k. We talk about it for a while and come to some<br />

consensus on its mean<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>the</strong> best way to answer <strong>the</strong> consumer’s<br />

question. I write it up, pass it around here, and send it out<br />

for review. 5<br />

The cognitive element of this basic description, “when I th<strong>in</strong>k I have an<br />

answer,” is a vague impression of <strong>the</strong> psychological processes that occur dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

analysis. The elements that are not vague are <strong>the</strong> historical, organizational,<br />

and social elements of analysis. The analyst checks <strong>the</strong> previous written products<br />

that have been given to consumers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> past. That is, <strong>the</strong> analyst looks<br />

for <strong>the</strong> accepted organizational response before generat<strong>in</strong>g analytic hypo<strong>the</strong>ses.<br />

The organizational-historical context is critical to understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

context, and process of <strong>in</strong>telligence analysis. There are real organizational<br />

and political consequences associated with chang<strong>in</strong>g official analytic f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

and releas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m to consumers. The organizational consequences are associated<br />

with challeng<strong>in</strong>g o<strong>the</strong>r doma<strong>in</strong> experts (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g peers and supervisors).<br />

The potential political consequences arise when consumers beg<strong>in</strong> to question<br />

<strong>the</strong> veracity and consistency of current or previous <strong>in</strong>telligence report<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Accurate or not, <strong>the</strong>re is a general impression with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> analytic community<br />

4<br />

In research, triangulation refers to <strong>the</strong> application of a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of two or more <strong>the</strong>ories, data<br />

sources, methods, or <strong>in</strong>vestigators to develop a s<strong>in</strong>gle construct <strong>in</strong> a study of a s<strong>in</strong>gle phenomenon.<br />

5<br />

<strong>Intelligence</strong> analyst’s comment dur<strong>in</strong>g an ethnographic <strong>in</strong>terview. Such quotes are <strong>in</strong>dented and<br />

italicized <strong>in</strong> this way throughout <strong>the</strong> text and will not be fur<strong>the</strong>r identified; quotes attributable to<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs will be identified as such.<br />

5

CHAPTER ONE<br />

that consumers of <strong>in</strong>telligence products require a static “f<strong>in</strong>al say” on a given<br />

topic <strong>in</strong> order to generate policy. This sort of organizational-historical context,<br />

coupled with <strong>the</strong> impression that consumers must have a f<strong>in</strong>al verdict, tends to<br />

create and re<strong>in</strong>force a risk-averse culture.<br />

Once <strong>the</strong> organizational context for answer<strong>in</strong>g any given question is understood,<br />

<strong>the</strong> analyst beg<strong>in</strong>s to consider raw data specific to answer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> new<br />

question. In so do<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> analyst runs <strong>the</strong> risk of confirmation biases. That is,<br />

<strong>in</strong>stead of generat<strong>in</strong>g new hypo<strong>the</strong>ses based solely on raw data and <strong>the</strong>n<br />

weigh<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> evidence to confirm or refute those hypo<strong>the</strong>ses, <strong>the</strong> analyst<br />

beg<strong>in</strong>s look<strong>in</strong>g for evidence to confirm <strong>the</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g hypo<strong>the</strong>sis, which came<br />

from previous <strong>in</strong>telligence products or was <strong>in</strong>ferred dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>teractions with<br />

colleagues. The process is re<strong>in</strong>forced socially as <strong>the</strong> analyst discusses a new<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g with group members and superiors, often <strong>the</strong> very people who collaborated<br />

<strong>in</strong> produc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> previous <strong>in</strong>telligence products. Similarly, those who<br />

review <strong>the</strong> product may have been <strong>the</strong> reviewers who passed on <strong>the</strong> analyst’s<br />

previous efforts.<br />

This is not to say that <strong>the</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>telligence products are necessarily <strong>in</strong>accurate.<br />

In fact, <strong>the</strong>y are very often accurate. This is merely meant to po<strong>in</strong>t out<br />

that risk aversion, organizational-historical context, and socialization are all<br />

part of <strong>the</strong> analytic process. One cannot separate <strong>the</strong> cognitive aspects of <strong>in</strong>telligence<br />

analysis from its cultural context.<br />

Def<strong>in</strong>ition 3: <strong>Intelligence</strong> errors are factual <strong>in</strong>accuracies <strong>in</strong> analysis<br />

result<strong>in</strong>g from poor or miss<strong>in</strong>g data; <strong>in</strong>telligence failure is systemic<br />