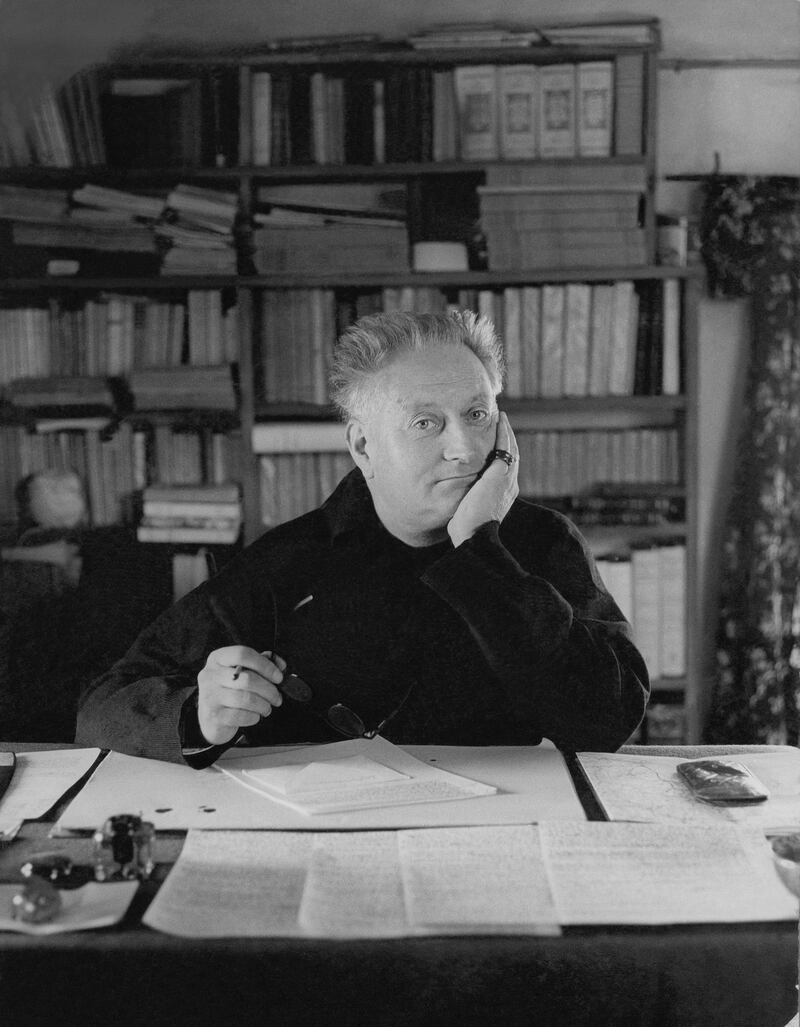

Jean Giono (1895-1970) was one of the most prolific French authors of the 20th century. Most of his prodigious output of fiction is set in the town of Manosque, Provence, where he lived for most of his life. Many of those novels depict cut-off communities under threat from hostile outside forces. In Giono's debut, Hill (1929), the inhabitants of a Provencal hamlet battle against the more savage elements of the natural world. In his 1947 work A King Alone, people living in a remote Alpine village are terrified by marauding wolves and a spate of disappearances.

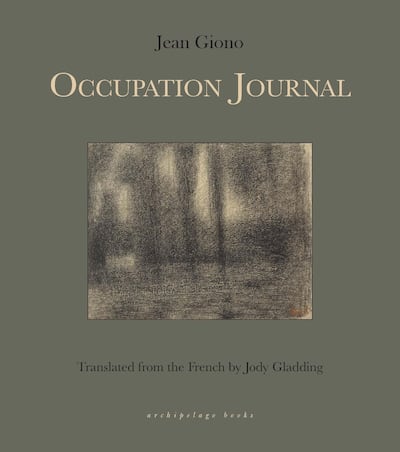

In the heat of the Second World War, Manosque and its environs were exposed to dangers from outside – first during the Nazi occupation and later during the Allied liberation. Giono not only survived this fraught period, but also wrote about it in detail in his diary. Occupation Journal was originally published in French in 1995. Now, 25 years later, it finally appears in English. Elegantly translated by Jody Gladding, the book is a fascinating account of ordinary life during extraordinary times.

The journal begins in September 1943, when Giono makes the decision to start writing again after a hiatus. There are distractions – a recent assassination attempt, the news that a fellow pacifist now works for the resistance – but soon Giono settles down and applies himself. He spends his days managing his small farms, caring for his large family and juggling three writing projects. “I have never been so happy as now,” he writes.

But over the ensuing months, his good spirits give way to black moods and bouts of self-doubt. He craves “organised solitude”, and worries about his finances and the on-off flow of his writing. And yet when the writing goes well, it has the power to work wonders on his self-esteem. “Nothing is more reassuring than knowing you are in the midst of a great enterprise.”

Then 1944 arrives and with it an increased German presence. Sometimes this has its advantages. In one comic interlude, a German officer and a soldier carrying a gun knock on his door – not to take him away, but to get signed copies of his books. But then the Allies step up their offensive to oust the Nazi occupiers, and Giono’s peaceful bubble bursts. Distant gunfire is replaced by more localised and more catastrophic assaults.

“Yesterday there was aerial combat over Manosque,” he writes. Marseilles is bombed and corpses lie scattered across the city for more than a week: “More than two thousand are still in the process of rotting under the rubble.” Giono tries to carry on as normal, but finds chaos at every turn. “The world seems to be collapsing into a general lack of quality,” he writes.

Occupation Journal shows Giono in many different lights. First and foremost he seems like a hardworking writer and a dutiful diarist (he provides a sizeable entry for almost every day). He describes his journal as "a tool of the trade". Compiling a record of everyday events is like "callisthenics", designed to build his muscles and hone his craft. "The point of practising these daily scales," he adds, "is to discover new tricks."

We also learn he was as an avid reader – reading being “the sensual pleasure of uncertain times” – of past French masters such as Stendhal and Balzac. In addition, he is a lover of nature, with many of his reports and ruminations containing memorable observations on flora, fauna or subtle seasonal changes. “The firs hunched over in their great coats,” he writes. Autumn comes, and with it “the first shiver that makes the warmth of wool sweaters and the inside of houses seem magnificent”.

Giono emerges as someone who was always prepared to lend a hand to those in need. Despite his dwindling resources, he pays for an employee’s stomach operation. Although he is “so unqualified and so powerless”, he appeals to the Gestapo to secure the release of luckless souls locked up in cells or awaiting deportation to concentration camps.

His defiant anti-war stance also led to him being imprisoned for six months for collaboration, although no charges were ever brought.

As diary entries offering a captivating portrait of an artist at work, a man under pressure, and a country in turmoil, Occupation Journal is a compelling read.