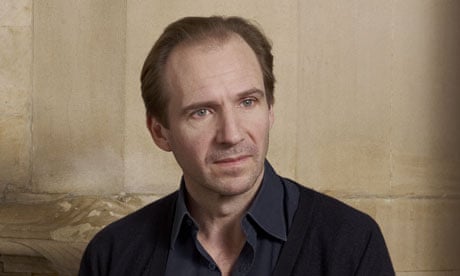

Ralph Fiennes could have been a diplomat in a previous life – the low, patrician voice, and the clothes. He is dressed on the morning we meet with an elegance that would not disgrace a Frenchman: neat cardigan, fresh shirt, polished boots. We are in Soho, in post-production offices – an editing suite like a gone-wrong sitting room, with a bank of computers at right angles to a sofa.

He is, by a month, on the youthful side of 50. And he has a smile of such disarming sweetness that the first impression is that something has gone bizarrely wrong. It is only retrospectively that the oddity makes sense: what he does best as an actor is torment. His eyes can convey a troubled history in a glance. They mark him out in every part, from MI6 agent in the new Bond film, Skyfall, to Voldemort in Harry Potter, an SS officer in Schindler's List, TE Lawrence in A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia, and Coriolanus, in the film he also directed. They are extraordinary. But if the lightness in his face this morning is unfamiliar, it should not be taken as encouragement. By repute, Ralph is anything but biddable. It is as if he really were an ambassador, overseeing a country of unrest.

It is breakfast time, and we begin with Dickens because Fiennes is in the middle of a Dickens-fest. In Mike Newell's new film, Great Expectations, he is one of a starry cast alongside Helena Bonham Carter's zany cobweb of a Miss Havisham, Robbie Coltrane's bullish Mr Jaggers and Jeremy Irvine – still fresh faced after War Horse – as Pip. Fiennes plays the unnerving convict, Magwitch, and captures perfectly that uniquely Dickensian mixture of the sinister and benign.

But he is also involved in a project even dearer to his heart. He is directing his second film, The Invisible Woman, in which he also stars – as Dickens. The screenplay, bys Abi Morgan, is inspired by Claire Tomalin's splendid biography about Dickens and the secret love of his life: Nelly Ternan. I ask how it would be were Dickens able to join us for breakfast. Would we like him? "I think we would be greatly taken with him. He would amuse us with his anecdotes. He would be very much the host. He would want to make sure we were all right and had enough to eat. We would be charmed." But would we get any sense of who he really was? "Possibly not. Whenever I meet people who are projecting one quality, I always think: what is the other side?"

It is a question with which Fiennes has been preoccupied during the making of his film, and will be my question too – but about Fiennes himself. What was Dickens hiding? "Everyone is quick to say Dickens was a bit of a shit, did not treat his wife very nicely … but he was churning with creative imagination. And if you don't have that inside you, it is hard to get your head around it."

Dickens was a compulsive walker, Fiennes says. "He wore himself out." He had an "obsessive quality, and when pushed into a corner could act with emotional violence". He was "profoundly sensitive, easily slighted, incredibly generous". Fiennes talks of the "yearning" in the novels, Dickens's recurring dream of finding a "perfect, harmonious place to live". It is wrong, he believes, to dismiss this as sentimentality.

Dickens's obsessive quality is something Fiennes understands. He is famous for his tireless approach to work, the self-criticism, the lack of complacency. What is most striking on meeting Fiennes is his concentrated quality. However, what drew him to The Invisible Woman was not Dickens but the character of Nelly (to be played by the wonderful, effervescent Felicity Jones). And now he springs to his feet and paces up and down, talking about Nelly, trying to imagine how it was for her: "He was 45 … she was only 18. And this man, this force that came at her, happened to be someone called Charles Dickens. And he came with his alpha-male charisma and imagination, and she had to weather it. And that was the story of her heart." He adds in a quieter tone: "And that made me want to do it."

Fiennes hadn't read much Dickens before the film got under way but he has put that right. And he talks about Dickens's feelings: the "shame, doubt and anguish" felt by a married Victorian in a love out of wedlock; the conflict between desire and duty, and the plain fact he "adored Nell". Dickens would have "worked hard to show he was there for her". I can hear in his voice his wish to believe in the unassailability of their love, yet he is swift to acknowledge how hard Nelly's lot became: "Here was a woman harbouring the secret of a past life. She lived with what I call a 'wound of intimacy'."

Quite a phrase. It makes one wonder about the "wounds of intimacy" in his own life. He lived for 12 years with the actress Alex Kingston, whom he married in 1993 but then left for Francesca Annis, 17 years his senior (she was playing Gertrude to his Hamlet on Broadway), until that relationship also ended. The rest is mainly gossip.

And to spare Fiennes this morning I have devised – for light relief – a multiple-choice question. I tell him what he is in for and he laughs and sits forward on the sofa.

You don't like talking about your private life because:

a) It is a bloody impertinence to be asked about it, and it's not the interviewer's business.

b) You are shy.

c) You prefer to be in control of the material yourself.

d) It involves other people, and that makes it uncomfortable.

e) None of the above.

He considers: "A combination … a) c) and d)."

This approach could revolutionise interviewing. And I can glimpse a playfulness there. But I want to know about his mother, who died of cancer when she was 55 and he was 31, and no multiple-choice answer could begin to cover that. She is one woman he will gladly talk about. "I was very close to my mother." Jennifer Lash – Jini to her friends – was a painter and novelist (Bloomsbury published her last novel, Blood Ties). Born in England, she spent her early years in India, and seems to have been creative, unconventional, high-maintenance – a huge influence on her children. "She was an enthusiast," he says. "She encouraged us all to engage. To really go into whatever we were doing, not to skate on the surface. To become impassioned." But she had "an emotional fragility – often present – that we all felt strongly".

Ralph is the eldest of six – seven, when counting his adopted brother, Michael. Sophie is a film-maker, and Martha a film director; Magnus is a composer and record producer, Joseph an actor, and only Jacob, a conservationist, has slipped through the artistic net. Ralph was himself initially balanced between art and drama, spending a year at Chelsea College of Art before going to Rada.

His directorial debut was last year's Coriolanus, in which he also played the title role. I ask about the overwhelming scenes between Coriolanus and his mother Volumnia (played by Vanessa Redgrave), and whether the relationship with his own mother influenced them. "If you play a mother-and-son scene you call on your own history with your mother, just as if you are playing a scene with a lover you call on situations you have had with a lover…"

Making Coriolanus was incredibly hard, he says. What did he learn? More than anything, directing has taught him a lot about acting. He talks of the pursuit of "this weird thing called the truth" and is fascinated by the "transparent" moments when actors go beyond acting and "everything falls away, and this thing comes through which is very pure". His task as director is to "winnow away" and harvest such moments. He tells a wonderful story about the Hungarian director István Szabó, who used to say (he mimics his Hungarian accent and a tone of kindly dismissal) "Yes, yes – very nice – prepared emotions."

It is unprepared emotions that make a performance. He talks of the late Anthony Minghella. Fiennes played the romantic lead in Minghella's The English Patient and he has been thinking about him while working on The Invisible Woman. "There are only a few directors who have a language for nurturing nuances of performance with any real skill. A lot of directors love their actors, admire and want to help them but he was exceptionally perceptive; he invested in teasing out, developing and nurturing."

We are meeting on the morning Skyfall opens. I see it on the evening of the same day. The way Fiennes looks in the film is larger-than-life yet uncannily close to how he appears in the flesh. The receding hair swept off the brow, the noble nose – which in a less handsome face could be too much of a good thing – and, of course, the feted eyes. In the film it is also possible to identify that this is a face with a depressive streak, with a little frown for punctuation. It is a pukka performance: he addresses Bond with patronising seniority, advising Daniel Craig he is playing a "young man's game" before sending him packing with the line "Good luck 007, don't cock it up."

Fiennes, along with the rest of the world, thinks Craig is "superlative …brilliant". He also salutes director Sam Mendes and John Logan, the Hollywood screenwriter who also adapted Coriolanus. Is Bond a part he would ever have liked to play himself? "As a teenager I was obsessed with him. When I was younger I might have fancied my chances … and actually, there was a moment 15 years ago when a few phone calls were made …" But he is too much of a thinker to play Bond, and, by his own admission, a lousy sportsman. And where would the torment fit in? Bond doesn't do torment, no matter how tough the going.

So, in lieu of any action man openings he is about to star in Wes Anderson's The Grand Budapest Hotel, a comedy about Monsieur Gustave, a concierge. But he has no plans to direct any more films: "I have loved it but it is a crazy test." Is it because he worries too much? "Isn't there such a thing as healthy stress?" he replies. I have never understood what that is. He laughs: "There is adrenalised stress. I love the shooting: ready – turnover – action … You don't know what is going to happen, and I don't just mean the acting but the weather, the light …" He compares the uncertainty to theatre, where his roots are.

How often does stress lead to anger? "I get angry easily but I sit on it, repress it. I have learned that anger is not cool, it is ugly, even though it might feel momentarily cathartic."

His anger as Coriolanus – a seething impatience under the skin, an imperious yet suffering eye (he can do disdain like nobody else) – was terrifying. "I know …it is in me, all that," he gives a helpless laugh. "But I really feel the best place for it is in performance."

In Great Expectations Magwitch says: "We can no more see to the bottom of the next few hours than we can to the bottom of this river." How good is he at living in the present? "I need to work on that. I live in anticipation. To be purely in the present is really hard."

What does he do to get away? "I love to travel away from this culture and be in India or Greece, or Jordan or Russia, or China …"

He lives in Shoreditch, where his brother Magnus was once memorably quoted as saying Fiennes lived "like a monk who has won the lottery". He doesn't know how much longer he will be there. Why not – is Shoreditch too trendy? "It makes me feel so old," he laughs.

Fiennes was born in Ipswich and spent the first six years of his life growing up in Suffolk. His photographer father Mark Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes (cousin to the adventurer Sir Ranulph Fiennes) was farming outside Southwold. It is, we agree, a stretch of coast that remains unselfconsciously itself. He loves that part of the world. "That is my early childhood, that coastline."

Would he consider living outside London? "Very much, I really would want that." I can't help thinking back to his remarks about Dickens's yearning for the perfect, harmonious place to live.

Did growing up as the eldest of six give him his taste for solitude? "I like solitude." But when pressed he hesitates: "I live on my own. It seems to work. It gives me a kind of headspace. Which I feel I need." And he gives me his I-am-my-own-worst-enemy smile.

Great Expectations opens on 30 Nov

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion