Twenty years ago, Douglas Coupland was at work when he sneezed. It was December, he recalls, and snowing hard, and it was the biggest sneeze he'd ever had in his life. "And there was this thing, like an entity, in my hand – the size, colour and shape of a really big green grape. And I freaked – what the fuck is that? It had veins on it, like it was an evil alien." He went to his doctor, who had a look inside Coupland's nose and said, "Oh well, it's not inside of you any more. It seems all clear up there now."

But what was it? "I don't know. But something got ripped, and after that, well it's been 7,000 sleeps since 1989, and I have to use earplugs every single night. I've never been able to focus sound since then. It's not so much the noise as the directionality of the noise; it's this weird, quirky thing."

We are sitting in the drawing room of a rather grand, central London hotel – a spacious, hushed room that we have almost to ourselves. But moments earlier, outside in the distance, some builders began work – and Coupland's face had frozen into a tableau of pain. "It's like someone starting to use those saws you hear at the beginning of Meat is Murder," he winces. "Is that the Meat is Murder saws going outside?" When a mobile phone in a far corner of the room sets off a twinkly ring tone, he freezes again. "Oh, sometimes I really don't like 2009. Use your indoors voice, not your outdoors voice!" he exhorts under his breath, as the phone's owner begins to talk. A pair of guests pass by on the landing, talking quietly together as they walk; Coupland tenses, then relaxes in relief. "That's good," he murmurs approvingly. "They're using their indoor voices. Good."

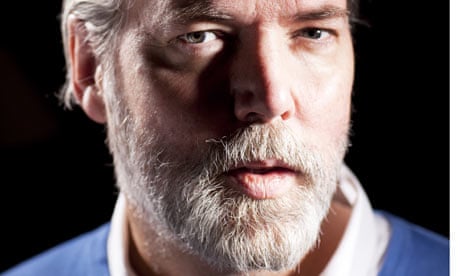

Coupland is not exaggerating when he describes himself as "sensitive" to noise. He speaks so softly himself, in a low gravelly half- whisper, that it can be quite hard to make out what he is saying. At 48 he looks older than his years – silvery grey hair and solemnly statesmanlike, with an introspective bearing that adds to the air of stillness around him – and were it not for his problem with noise, he might appear forbidding. But the freezing and wincing at every background noise makes him seem unexpectedly vulnerable – not intolerant but, rather, touchingly defenceless. The condition may also, more importantly, help to explain the novelist's famously singular and highly unusual way of looking at the world.

"The whole episode with the grape," he explains, "got me interested in how we sense things. I think synaesthesia is the word everyone uses – how senses overlap with one another. With the grape thing, it wasn't wiring that got ripped out, but some new link that was established. I think a whole lot of wires are going the wrong way."

Only the day before we meet, he had been in a branch of Paperchase when a sheet of multi-coloured hexagonal wrapping paper so mesmerised him that, after a while, staff had to approach the spellbound novelist, taking him for some sort of crazed drifter. As he is telling me this, his eyes feast on the colours of the drawing room. "I don't know if you get this," he rasps softly, "but I feel like I can just stare at a recently opened bucket of paint for minutes, just . . . yeah." For the colour or the smell? "Well, when the paint's wet in the can, it's just so – it's optical, but it's edible as well." He gazes into space for a moment, looking dreamily blissed out. "You think, ooh, what would it feel like to eat?" It is at this point that I quietly put aside all the questions I'd prepared, and surrender to an entirely different register of conversation.

The conventional interview arrangement, whereby a subject broadly answers questions, is so far removed from the way Coupland interacts with the world as to be almost comically hopeless. The very concept seems meaningless to him; instead, we digress along conversational pathways that lack any discernible logic or direction. But the freeform ruminations are not, I think, some kind of writerly affectation. It really is as if his mind is wired quite differently from most people's – and once you succumb to its idiosyncratic rhythm, it becomes strangely beguiling.

Coupland is in London to promote his latest novel, Generation A – a darkly humorous but eerie tale set in the near future, about five protagonists leading unconnected but recognisably globalised lives in disparate parts of the world. It is a world in which bees have become extinct, but when all five are mysteriously stung, they find themselves drawn together into a vaguely Orwellian narrative. Weaving stories within stories, the novel consciously evokes echoes of Coupland's first novel, Generation X – the classic 1991 bestseller that introduced us to slackers employed in McJobs, and conferred on its author the reputation of a futuristic visionary.

Coupland, however, seems charmingly indifferent to the duties of a publicity tour, and happy to forget about the new book. Instead, he talks about his current art projects. A graduate of art school in his native Canada, as well as Italy and Japan, he more or less fell into writing by accident in the late 80s as a way to fund his art work, and still sees no distinction between the forms. "People say if you're doing an art project, that's different from a book, but I honestly don't see it. I try and try, and I just don't."

He tells me about the towers of empty food tins – "like consumer minarets" – he's been building, and another project that involves collecting plastic lids. "We're taking the caps, putting resin in them to make them stable, then drilling through them and making these really tall, skinny, beautiful towers. It works out about $5 [£3] an inch. I don't sell them, I keep them." Where does he keep them all? He laughs.

"Well, my house. It's kind of eccentric. It's two decades worth of accumulated personal projects. Yeah, it is pretty dense in my house." Coupland lives in the woods near Vancouver, and can never discard a project, he explains, "because an object is interesting because it's the crystallisation of a good idea. And I like being surrounded by good ideas. Every single time you walk past something you like, you get a blast of happy chemicals to the brain, and I like that." Moments later, he mentions that things have got so crowded at home that he has had to buy the house behind his, just to have somewhere for people to come for dinner without banging their heads.

"A different person would probably have bought a bigger house," he adds, almost as an afterthought. "But I'm too bonded to the place. I could never sell."

And thus, quite by accident, we appear to have stumbled on what has always felt like the great paradox at the heart of Coupland's work. He always describes himself as "pro future" – or a "futurist" – and his reputation as a techno-cultural soothsayer, established by Generation X, was confirmed by later bestsellers such as Microserfs, the first literary work to recognise the power of Microsoft. He is even said to greet old friends by reference to technological innovations – "Hey, I haven't seen you since the iPhone was invented," and so on. And yet the protagonists of Generation X were already nostalgic for the past era of Eisenhower plenty, and the future depicted in Generation A is a dark conflation of recession, climate change, globalisation and lonely alienation.

Surely, I say, a man who predicts a future like that – and won't even sell a house he has outgrown – has to be more of a nostalgist than a futurist? He smiles slowly.

"Well, the phrase I would use now is that I'm quite open about the future. I'm curious. In my mind I've always checked out in 2037; that's always been my expiration date. I'll be 75. And I just go fucking nuts not being able to know what comes after that."

Coupland's past has always been somewhat opaque; the second of four sons of a medic in the Canadian air force, he was born on a Nato base in Germany, grew up in British Columbia, and credits his parents with providing a "blank slate" for a childhood that he describes as happy, if unremarkable. About his present he is also quite private; he publicly came out only three years ago, and does not mention a partner. But his life in the Vancouver woods, surrounded by art projects as he works on his 14th novel, sounds pretty content. If the world in 2038 really does resemble the one he foretells in Generation A, I ask if that could truthfully feel to him like progress.

He considers. "Hmmm. I remember the 70s really well, and the thing about the 70s was everything was just decaying, nothing worked, either politically or in any other way. And the only technological changes were that phones went from rotary to push-button. Then in the 80s there were a few more things, and in the 90s there was email, but even if you had it there weren't many places to go with it.

"And then, suddenly, collectively, since 2000, we've had Google, Ebay, Facebook, social media, the digitisation of the world's economic system, the iPhone. My friend's got an iPhone you can point at a sudoku puzzle in a news-paper, and it recognises the numbers and builds you a new electronic one, and then it solves it for you in about three seconds. It's just voodoo, it's totally spooky."

It certainly feels like that to me, I agree – but then, I'm a nostalgist. How does it feel to him, watching "voodoo" develop? "It's kind of like watching David Blaine levitate or something. I don't mind it. The world just continues to be incredibly interesting, and not just in the Chinese curse sense." Coupland speaks slowly, and gives the appealing impression of thinking as he goes along, rather than rolling out thoughts with which he is already long familiar.

"I am pretty good at extrapolating from the present," he continues. "But I think if you talk about the future too much, which I guess is what I do, people just think you're a cheerleader for it. And I'm not a cheerleader for it. But if everyone's doing something, I won't judge them. I mean, I think half the people who get married now have met online. If I think about all the people in my life who married – they met online, online, online. And it makes sense if you think about it, because you fill out this form of 35 things that really define you and – bam – look, you've got two people who match. It works. It is kind of robotic though," he laughs.

Then he adds, "This friend of mine who's a hotel bartender, he says he can always tell the internet dates when they come in. The first person comes in with a certain kind of furtiveness, then the other person arrives, and apparently it either happens within three microseconds or it's just like this was a horrible mistake, nice to meet you, bye. Literally, three seconds. It's instantaneous. There's still that body-to-body typing thing."

You see, I laugh – that's a nostalgist's argument, isn't it? But Coupland just smiles an enigmatic smile, before volunteering another example of what sounds like the opposite of enthusiasm for the future.

"Now that optical recognition technology has come in, Google could take a book, put it on a scanner, and the computer turns it into a digital file that you can search. There's a frightening amount of information suddenly; in a year, kids will be scanning all my books, the menu of what they ate for lunch – all they'll have to do is point and click and it turns everything into a file, so the entire planet becomes searchable. I do think that is very spooky, and I don't like it at all." You see, I pounce again – the future is a terrible place!

In the end I never really understand what Coupland feels about the future, but he doesn't seem to mind. Apart from noise, nothing seems to trouble him terribly; he expresses limitless curiosity rather than opinions, and when I suggest it's a value-free kind of curiosity, he agrees at once. "Yes, it is apolitical, that's it. Adding judgment, I've always thought, will muddy my ability to see the things I enjoy looking at. I'm not a monster," he adds quickly, grinning. "I'm sure we pretty much agree on everything, but my new curiosity is, will judgment cloud my view?

"I like it that people are smarter, that every-one can find facts quicker, and it does make people more interesting. But what happens – and this is the thing I'm not really sure about – when it comes to the point where people don't actually do anything any more? They just cut and paste from things that happened in the past. You can't download getting your hands dirty. Younger people don't think that way, they wouldn't mourn the passing of a manual universe – it's just ridiculous to even think about for them – so they'll miss something you and I have experienced. But they'll have something else they've experienced too, so, um . . ." He tails away, lost in thought. "You've got me in this loop now, about whether I should be moral about being amoral – which is the crisis of modernism in one sentence."

A friend asked him recently, if he had the choice would he go back to the 90s? He might as well have suggested returning to the middle ages; Coupland was horrified.

"No! Because I would miss the sense of frontier that we have right now. Soon it won't be the internet any more, it'll just be like air, like somehow they'll integrate the internet into the air. And God's name will have ended up being Google, because that's the way it worked out.

"It could have worked out that God's name ended up being Yahoo, of course," he adds. "But they lost out."