A tubercular alcoholic, addicted to women, hash and ether, unrecognised, impoverished and dead at 35 with the last painting still wet on the canvas: Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920) is a Romantic throwback in 20th-century art. Even his nickname, Modi, is a pun on the peintre maudit, the accursed painter, a phrase coined half a century before he was born. He starts as an outsider, a Jew in Catholic France, an Italian immigrant reciting Dante in Montmartre, and ends as a rachitic wreck still trying to make a franc from his enchanting portraits of Parisians. How could such a tormented life produce such serene work?

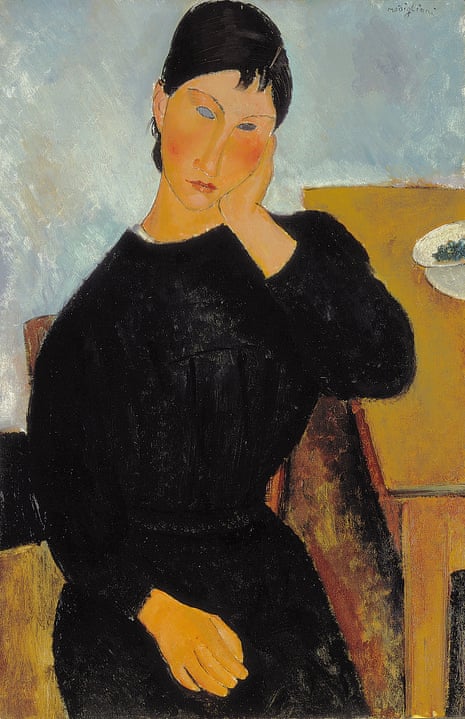

For that is the atmosphere of Tate Modern’s exemplary survey of Modigliani’s short-lived career. The show is beautiful, endearing, evenly elegant: one hundred portraits, including some of his best, painted over the 14 years that Modigliani lived in Paris. You may think you know him – the long, oval faces and almond eyes, the palette of pink, blue and chestnut, the tubular necks and curvilinear limbs, all that grace and sorrow compounded by the artist’s own tragic existence. And it turns out that you do.

For although this is the largest UK show ever, it is marked by an almost total lack of surprise: here they all are, wistful and sweet as children, filling room after innocent room.

The first gallery is the only jolt, bringing you face to face with a Cézanne musician, a Picasso Pierrot and a stylish Parisienne by Toulouse-Lautrec, among others – all painted by Modigliani himself. He also looks as hard as everybody else at African carvings. But the learning is soon over and he’s conflating hints of these many sources, as well as Botticelli and Parmigianino, into the elongated figures for which he is known, a streamlined mannerism for the early 20th century.

There were sculptures, carved from stone nicked from building sites. With their pursed mouths and improbably long noses, these massive heads appear both ancient and modern, and more spiritual than the usual avant-garde plundering of African art. Sculpture also helps Modigliani simplify forms. His real ambition, he once said, was to work in stone, and there’s a fixity and incision to all his painted portraits. He looks at a face and makes a mask, no matter how mobile or volatile the sitter.

The results can be superb. The portrait of his first dealer, Paul Guillaume (despite the myth, Modigliani had several patrons), is all nervous arrogance, the head tilted back, the gloved hand fastidiously cocking a cigarette. The basic grammar of ovals, arcs, cupid-bow lips and circumflex noses is there. And the tense image of Jean Cocteau, around the time of his collaboration with Diaghilev in 1916, is a brilliant concatenation of triangles, blade-sharp as its elegant subject. “It doesn’t look like me,” Cocteau remarked, “but it does look like Modigliani, which is better.”

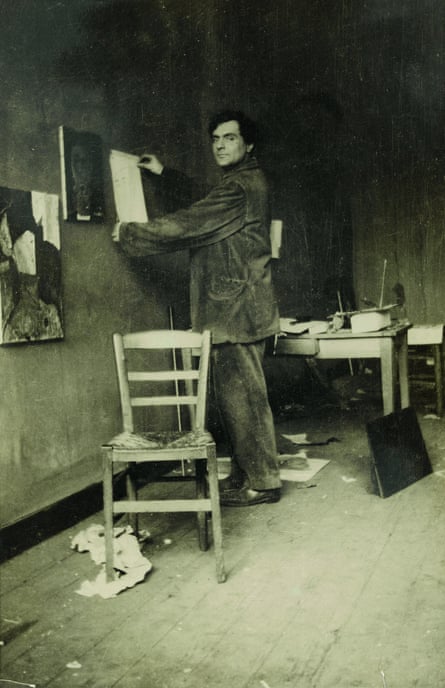

He did not mean that it resembled the artist himself, whose handsome face looks out of period photographs and films at Tate Modern – the Moulin Rouge slowly revolving; artists flitting between garrets, hauling their canvases by cart (including, in one case, the very nude you’ve just been looking at). Modigliani’s final studio, incidentally, is brought to startling life in a virtual reality suite where you sit before his easel as the Paris sunlight pours through the open casements and the last cigarette dies in the ashtray.

Cocteau was speaking of Modigliani’s idiom, his elongated outlines and the tonal gradations borrowed from Cézanne. The Italian was famously fast, painting the sculptor Lipchitz and his fiancee in two rapid sittings so that Lipchitz invited him to work longer for better wages; those lariat lines are as quick and virtuosic as they look. They come into their own especially with the nudes, those pink-and-ochre diagrams of beauty, less erotic than smoothly curvilinear. It remains astonishing that police tried to close down Modigliani’s only solo show in 1917 because of the pubic hair, neatly tidied into more Modigliani triangles.

The look fits some better than others – the already delicate, for instance. It is not ideal for the Spanish painter Juan Gris, swarthy and broad, or for Picasso, portrayed so haphazardly he could be practically anyone. Modigliani revered Picasso, particularly his muckle portrait of Gertrude Stein with mismatched eyes. His own depiction of eyes, one sighted, the other an opaque lozenge of blue or grey, aims for quizzical estrangement. But when you have seen it 20 times it looks like a trick from the box, the effect undone by sheer repetition.

And that is, alas, the weakness of a full-scale Modigliani retrospective. His style becomes a manner (and so easily imitated it has lead to an epidemic of fakes). His characterisation dwindles to caricature. It is by no means clear that he is looking for the uniqueness of each person who comes before him in any case, although of course there are exceptions, above all the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, with whom he once shared a studio. In this magnificent portrait from 1914, Rivera appears in full force and bulk, the bulging eyes half-shut with pleasure, the paint nubbed like pocked skin, the moist lips insalubriously gathered into a kiss.

If it is hard to believe that the nudes were once “banned”, in Tate Modern’s sensationalist phrase, it is equally hard to think of Modigliani now as a radical painter. This is not just because his art is so attractive, in its lithe and dancing rhythms, the paint laid down with such graceful finesse. Or even because these not-quite likenesses can be so ingratiating, and sometimes even cloying. It is more that his kind of modernism, which now looks so old-world, consists in this constant stylistic reiteration.

Perhaps, in a life so short and tortured, there was very little chance to do more than keep on holding the brush. But there is rarely any sense of ambition for his portraits beyond this look of serene impenetrability. Even in the late paintings of Jeanne Hébuterne, Modigliani’s mistress and the mother of his only surviving child (she killed herself two days after Modigliani’s death, nine months pregnant with their second baby), there is a pervasive detachment; only when he gets right up close, inches from her face, is there a spark of engagement.

It would be too much to say that Modigliani’s art never varied. His line gets leaner, his shape-making more original and unexpected the further he gets from the painter-gods of his youth; and there is a tenderness here that can’t be feigned, as if he truly loved painting and people. But it feels as if Jean Cocteau had it right. You sat for this artist and were gone, disappearing into a Modigliani.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion