Old Master Prints

Old Master Prints

Albrecht Dürer

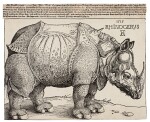

The Rhinoceros (B. 336; M., Holl. 273)

Lot Closed

December 9, 02:04 PM GMT

Estimate

150,000 - 200,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

Albrecht Dürer

1471 - 1528

The Rhinoceros (B. 336; M., Holl. 273)

Woodcut, 1515, a very good, rich and black impression of Meder's second edition, with the fine crack in the right hind leg just starting to show, on paper with a Small Urn watermark (M. 168, circa 1540), with the letterpress text of the fourth edition, framed

sheet: 243 by 295mm 9½ by 11⅝in

The fineness of the crack through the rhinoceros's right hind leg suggests that this impression is an early one from the second edition, printed in 1540. However, the letterpress text is from the fourth edition, indicating that the image and text were printed separately. We can assume that the image was printed 10 years before the text, and stayed in the workshop in the meantime.

With Christie's London, December 2013, lot 43 (£170,500)

On 1 May 1513 was brought from India to the great and powerful king Emanuel of Portugal at Lisbon a live animal called a rhinoceros. His form is here represented. It has the colour of a speckled tortoise and it is covered with a thick shell. It is like an elephant in size, but lower on its legs and almost invulnerable. It has a strong sharp horn on its nose, which it sharpens on stones. The stupid animal is the elephant’s deadly enemy. The elephant is very frightened of it, as, when they meet, it runs with its head down between its front legs and gores the stomach of the elephant and throttles it, and the elephant cannot fend it off. Because the animal is well armed, there is nothing that the elephant can do to it. It is also said that the rhinoceros is fast, daring and cunning.

This inscription accompanies Dürer’s monumental and hugely important woodcut, The Rhinoceros (1515). As is outlined in the text, the beast that inspired the print’s creation was gifted to King Manuel I of Portugal in 1515 (the date suggested in the inscription is erroneous.) It was the first rhinoceros to be seen in Europe since the age of the Roman Empire. Unsurprisingly, its arrival to the continent in modern times was met with great excitement.

Dürer, like the majority of his European contemporaries, did not see the animal in the flesh. This fact is now readily assumed, given that his depiction diverges so markedly from the actual form of the subject, which does not comprise armoured plating or a spiralling horn between the shoulders. Dürer’s fantastical rendering was formalised by the wide circulation of the print—which was enormously popular—and by subsequent illustrations in natural histories and reiterations by other artists. This imagined rhinoceros thus became accepted as a true likeness of the animal until the eighteenth century.

Fortuitously, the imagined and somewhat embellished version of the rhinoceros allowed Dürer to demonstrate his capacities as a printmaker at this mature stage in his career. Eleanor Sayre has described the artist’s ‘innate gifts for elaborate detail and expressive, calligraphic line’ (Sayre, Albrecht Dürer: Master Printmaker, 1971, p. xxii), aptitudes that are clearly exhibited in the immense, emotive, and intricately ornamented creature depicted here.

In this image, Dürer also fully exploits (or perhaps surpasses) the potential of his medium. In his lifetime and to this day, the qualities Dürer was able to achieve in his monochromatic graphic works have consistently astonished viewers. Just prior to Dürer’s death in 1528, the great humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam captured the artist’s abilities by comparing him to Apelles, the famous painter of antiquity. Significantly, Erasmus did not describe Dürer as a painter but as a printmaker. He explained: ‘Dürer … what does he not express in monochromes, that is, by black lines? Shade, light, radiance, eminences, depressions… These things he places before our eyes by most felicitous lines, black ones that is … And is it not more wonderful to accomplish without the blandishment of colours what Apelles accomplished with their aid?’ (Quoted in Seifert, Dürer's Fame, 2011, p. 9)