Threading a 40t crane through a Grade 1 listed 18th Century gatehouse was just one of the challenges facing the team on a historic site in London.

Bart’s hospital first opened its doors in the 12th Century, and has occupied the same site ever since. Much of its impressive architecture is Grade 1 listed.Some dates back to medieval times and is classified as a Scheduled Monument. So slotting in an unashamedly avant garde building into such sensitive surroundings was always going to be a major challenge for designers and contractors.

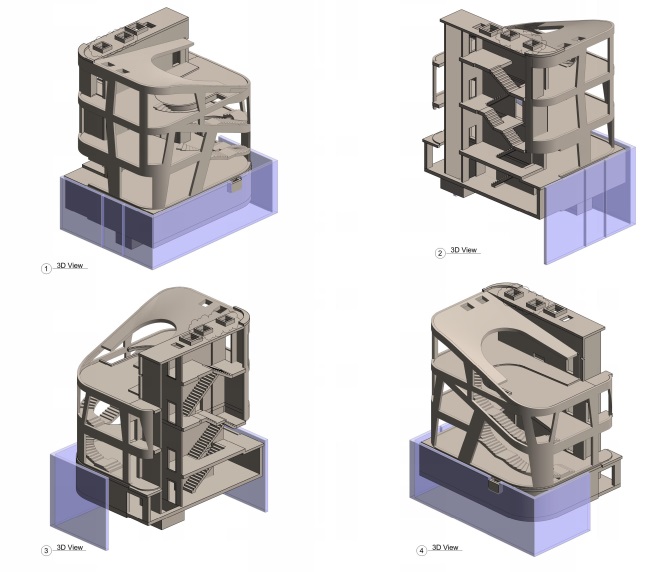

Axo arup

Asymmetrical curves and angles create a branching concrete frame.

Replacing an unremarkable brick clad 1960s building tacked onto one end of the hospital’s 18th Century Great Hall is the latest in a long series of Maggie’s Centres. These offer free practical, emotional and social support to cancer sufferers and their families, usually in iconic buildings designed by leading architects. Virtually all of these are low rise: at Bart’s the restricted footprint of the Maggie’s Centre site required the architect to go for a three storey, plus single storey basement design.

On such a historic site it might be expected that basement and foundation design could be dictated by unpredictable discoveries below ground. Structural engineer Arup associate Derek Roberts, however, says there were no major obstructions.

“A 10 week archaeological investigation only revealed a Roman defensive ditch running diagonally across the site, and seven skeletons from the Roman period.

Maggies progress 29 06 17 0018

Progress on site, 29 June

“Most of what was uncovered was the remains of Victorian cellars and medieval foundations.”

Of more immediate concern was the early 20th Century service duct that crosses the site just outside the new building’s footprint. Proximity to one wing of the Georgian hospital buildings also posed an unusual challenge, Roberts adds.

“The building close-by houses a high-tech machine called a gamma knife, which is used to treat brain cancer. As a result, we had always to minimise vibration, particularly when driving the sheet pile basement walls.”

Barts main entrance

Bart’s hospital, main entrance

A Giken “press-in” piling rig was the solution to this particular challenge. The fully tanked basement is just above the water table, while the 500mm thick raft foundation sits on the interface between the underlying sands and clays.

Logistics were perhaps the biggest headache for the site team. “Everything has to come in through the Henry VIII gate, then take a sharp left around the church of Saint Bartholemew the Less, which was built in the 15th Century,” explains Sir Robert McAlpine project manager Mark Love.

“There was never more than 100mm clearance around the crane as it went through the gate, and the piling rig was also a tight fit,” he says.

The narrow passage between the church and the Great Hall gives access to a very restricted site, with only around 50m2 outside the new building’s footprint available for the crane and materials storage. Luckily, the project team was able to find a home in the Grade 1 listed gatehouse itself, which dates from 1702.

“We had to refurbish the office and welfare spaces,” Love reports. “In the process we discovered a 1m square hole in the roof – which explained the puddles on the floor.”

At first sight, the main structure of the new Centre is bafflingly complex. Asymmetrical curves and angles create what New York-based architect Steven Holl dubs “a branching concrete frame…that branches like a hand”. The design stems from an early-morning watercolour sketch by Holl, who envisioned the building as a “vessel within a vessel within a vessel.”

Img 1506 (1)

The frame was finished with translucent matte finished glass cladding with coloured glass inserts.

Translucent matt finished glass cladding with coloured glass inserts forms the outer “vessel”, while internally the fair face concrete structure remains exposed on the vertical elements. A solid bamboo balustrade wraps around the winding open internal insitu concrete staircase. Cantilevered from the main frame, this stair links all three stories.

Roberts describes the design as “geometrically challenging” – something of an understatement. He adds: “The floor to ceiling heights are up to 4.85m, and the roof itself was particularly difficult, with tricky twists and warps.”

Although floors were polished and aggregate exposed on the stair tread and risers, there was no requirement for an unusually high standard of finish on most of the exposed frame. A straightforward C40 mix was supplied by London Concrete and skipped into place. Forming the complex geometry turned out to be rather simpler than might be expected, says Love.

Maggies progress 29 06 17 0006

The restricted site called for a four storey structure.

“Basically we used 4.5m high paper-faced ply formwork and created the shapes by box-outs. Wall thickness was a constant 350mm.”

He also pays tribute to falsework subcontractor Realtime Civil Engineering.

Linking the new centre and the Great Hall was fairly straightforward, Roberts reports. The two buildings will share a new lift and access stairs, with the shaft inside the Centre, despite a significant disparity in floor levels that presents users with more choices than usual. There will be new toilets for the Great Hall in the Centre’s new basement.

There is very little tolerance between the distinctive cladding panels, Love says. He adds: “But they’re getting on very well, probably because we constructed a full-scale mock-up on site right at the beginning, and learned a lot from that.”

When the new Centre opens next spring it will be topped by a roof garden, an oasis of tranquillity amidst the bustle of one of London’s busiest hospitals. By then its controversial architecture is likely to be much better accepted, and those who need its unique services are likely to be the most appreciative.

Who is Maggie?

Since 1996 no fewer than 21 Maggie’ Centres have opened, all but one in the grounds of NHS hospitals. The exception is the Maggie’s Centre in Hong Kong, which moved to a permanent home in 2013. Most are associated with big name architects, such as Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid and Richard Rogers: but the question most people ask is “Who is Maggie?”

A talented writer, artist and garden designer, Maggie Keswick Jenks was married to the writer and landscape architect Charles Jenks. In 1993 she was told her breast cancer had returned and her life expectancy was as little as two months.

She then took part in an advanced chemotherapy trial, living for another 18 months before dying in 1995 at the age of 54. During her final months, Maggie and her husband set up the Maggie Keswick Jenks Cancer Caring Trust (which now refers to itself simply as Maggie’s), dedicated to the idea of providing drop-in centres open to all who have been affected by cancer in some way.

Both she and her husband believed in the power of buildings to uplift and inspire. The first Centre, housed in a converted stable block in the grounds of the Western General Infirmary, Edinburgh, opened in 1996.

Hospital’s revealing history

The Royal and Ancient Hospital of St Bartholomew, to give Bart’s its official title, has been on this site since 1123. Founded by Rahere, rumoured to have been a court jester who saw the light and became a monk after recovering from illness, the hospital survived both the dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th Century and the Great Fire of London, which reached as far as the hospital’s gates.

Archaeological investigations over the years revealed that this prime site, close to St. Paul’s Cathedral, has been continuously occupied since at least Roman times. The discovery of seven Roman skeletons, possibly including those of soldiers, during an investigation of the Centre site is hardly surprising, given that a major Roman cemetery was located here.

During the 18th Century the hospital went through a decades-long major reconstruction. The first structure to be built was the Henry VIII gate, which displays the only public statue of the eponymous monarch in London.

New Civil Engineer Civil engineering and construction news and jobs from New Civil Engineer

New Civil Engineer Civil engineering and construction news and jobs from New Civil Engineer

Have your say

or a new account to join the discussion.