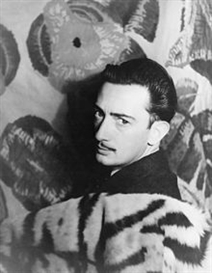

Once Upon a Time: Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou

The surrealist film, made up solely of blatantly irrational scenes, drew some shock reactions, yet not enough, according to its creators

Benjamin Blake Evemy / MutualArt

Feb 17, 2023

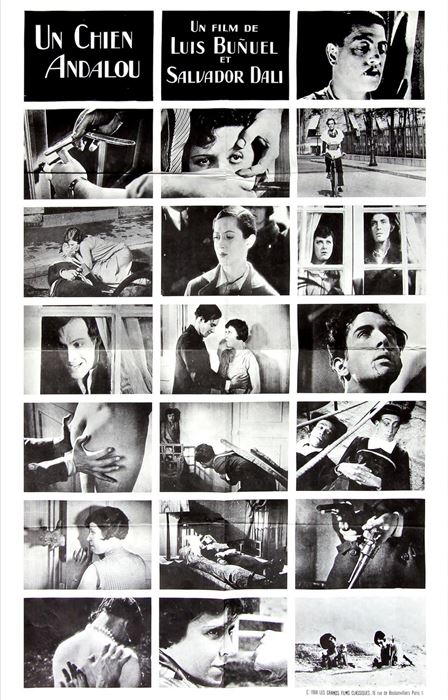

A title card reads “Once a upon a time:” a heavy-set man sharpens a straight-razor, cigarette clamped in jaw, before standing on a nighttime balcony and staring up at the full moon, as if to receive its blessing. The razor is then taken to a woman’s eye. Eight years later, the same woman is unchanged, eye intact. Ants craw out of a hole in a young man’s palm. A death witnessed in the street below acts as an aphrodisiac for an almost-ravishing before dead donkeys upon pianos are pulled across the room – a burden which banishes desire. These are some of the opening scenes of Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s 1929 surrealist silent short film, Un Chien Andalou, aptly setting its mood and tone, and hinting at what chimerical delights are sure to follow.

From Un Chien Andalou (1929)

In typical surrealist fashion, Un Chien Andalou has no plot in the conventional sense. Stitched together from seemingly disparate scenes, the film is a phantasmagoric nightmare, dream logic being the only defining rule. Freudian free association was extremely popular within the surrealist movement, and in fact the film’s genesis was found in dreams of both Buñuel and Dalí. While working as an assistant director for French filmmaker Jean Epstein (known for his 1928 adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher), Buñuel recounted a dream he had had to Dalí while at a restaurant. In this dream, a cloud sliced the moon in half “like a razor blade slicing through an eye.” Dalí responded with an account of a dream he himself had had, where a human hand was covered in crawling ants. This sparked a creative fervency in Buñuel, and he excitedly told the Spanish surrealist, “There’s the film, let’s go and make it.”

From Un Chien Andalou (1929)

The film’s title is a reference to the saying in the filmmakers’ native Spanish: “¡el perro andaluz aúlla, alguien ha muerto!” – which in the English translates to: “The Andalusian dog howls –someone has died!” The screenplay was written in a few days, a study of sorts on what the psyche could produce when dealing with the subject of suppressed desires and emotions. Buñuel and Dalí adhered to only one rule while working on the script: “Do not dwell on what required purely rational, psychological, or cultural explanations. Open the way to the irrational. It was accepted only that which struck us, regardless of the meaning ...” In other words: “No idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted.” This ensured that everything that made it into the final script worked purely on a subconscious level. The script came together with the utmost ease, with not one argument between its two writers. If any idea presented was objected by the other, it was immediately discarded without further discussion.

From Un Chien Andalou (1929)

This approach was in direct opposition to that taken by contemporary French filmmakers of the time, such as Jean Epstein, where every scene and subsequent shot had to possess a rational explanation and fit harmoniously into the whole. In his 1939 autobiography, Buñuel further explained the Surrealistic approach that was taken in regard to Un Chien Andalou: “The film was totally in keeping with the basic principle of the school, which defined surrealism as 'Psychic Automatism,' unconscious, capable of returning to the mind its true functions, beyond any form of control by reason, morality, or aesthetics.”

Since the pair did not possess much in the way of money, Buñuel’s mother financed the film, and it was shot over a period of ten days in March 1928. Even with Buñuel’s mother’s alms, the final scene had to be rewritten due to financial restraints, and Buñuel ended up editing the film in his kitchen, without access to any technical equipment, such as a Moviola (a device which enables the editor to view the film while in the process of editing).

From Un Chien Andalou (1929)

Un Chien Andalou was at first released in a limited capacity at Paris’s Studio des Ursulines cinema for the viewing pleasure of the Le tout-Paris, but due to its popularity ended up running for eight months. Such luminaries present at the premiere included Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso, Le Corbusier, and André Breton’s group of surrealists. Both Buñuel and Dalí expected significant drama to ensue following the screening, but it wasn’t so. Buñuel found himself surprisingly relieved that no acts of violence manifested, and he had purportedly filled his pockets with stones in anticipation “to throw at the audience in case of disaster,” while Dalí was slightly crestfallen that the excitement of the evening was considerably lessened by the audience’s civilized reaction. But despite Buñuel’s relief that he didn’t in fact have to use his pocket projectiles, he still found himself frustrated at the audience’s acceptance of the film, as, after all was said and done, he did intend to shock Paris’ intellectual bourgeoisie. It is likely that, since the film’s initial audience was comprised of many of the city’s artistic elite, they viewed the film with minds that were open to the strange and often violent scenes that Un Chien Andalou presented to their visual senses.

But Buñuel and Dalí’s anticipation of the uproar Un Chien Andalou would likely cause was not completely in vain, for during the film’s subsequent eight-month run, the audience was not always as accepting as that of the premiere. As many as fifty informers approached the police demanding that such a cruel and indecent film be banned immediately, and it is rumored that two miscarriages took place while the film was being screened. Buñuel himself would also be haunted into his old age by a barrage of insults and threats.

Original Poster for Un Chien Andalou (1929)

The legacy of Un Chien Andalou prevails to this day. Dalí and Buñuel were the first filmmakers to be officially welcomed into the ranks of the surrealist movement by André Breton, and a sequel, L’Age d’Or, was commissioned and released in 1930. The film has also struck a chord with musicians throughout the years since its initial release: it was shown before every concert on David Bowie’s 1976 Isolar Tour, and the lyrics of the Pixies song “Debaser” are inspired by the film. It has also been speculated that Un Chien Andalou became a blueprint of sorts for the modern music video. After almost 100 years, despite the advances in cinematic technology, the film’s opening sequence still holds significant power, continuing to both attract and repulse viewers to this day.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page