A John Currin Thanksgiving

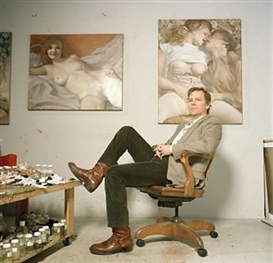

The American provocateur is a master at evoking uncomfortable truths in his paintings’ viewers, but after facing heavy criticism for his motifs, Currin had to re-navigate and found a new victim in masculinity

Michael Pearce / MutualArt

Nov 04, 2020

The American provocateur is a master at evoking uncomfortable truths in his paintings’ viewers, but after facing heavy criticism for his motifs, Currin had to re-navigate and found a new victim in masculinity.

John Currin - The Producer, 2002 Oil on canvas, 48 x 32 inches (121.9 x 81.3cm) © John Currin. Courtesy Gagosian

As the decades around the millennium turned, the prurient painter John Currin found fortune and fame by twisting together the hot issues of sentimentality and sex in a mawkish reality television housewife world, simultaneously exploiting both the prudish complaints of the cognoscenti who insisted that his paintings were harmful to the public, and the enthusiasm of his independent collectors who were keen to resist the finger-wagging of the self-righteous. Peddling painted pornography during a rising tide of censorship, he was an erotic bootlegger in prohibition, a provocative hero to sensualists, a voyeur adventurer lifting the vanilla veil from the nostalgic vision of nuclear America, showing how things might have been behind the scenes of Norman Rockwell’s popular imaginary realm, where anorexic but perky fifties housewives wiggled out of pencil dresses, threw them aside and fornicated like porn stars from a Hallmark card, stripping pretense from an artificial world where the thanksgiving turkey was toxic and salmonella-infested, and where pregnant new-look Cosmo readers bore babies like low-slung and over-inflated beach balls.

Romantic would-be Romeos and Juliets watch their beloved with secret desire in their vulnerable moments, as they bathe, change clothes, apply make-up in the mirror, but when they’re caught at it they look away to avoid causing embarrassment – this averted gaze is a customary ritual of pretended privacy. But if they keep looking when they’re caught, they’re lusting. And that was Currin’s cheerfully brazen gaze – lusting over dirty boudoir pastiche porno pinups clad with nostalgia. It was the same voyeur’s gaze that admires Félicien Rops’ delightfully decadent pornography, admires the saucy seaside postcard crudity of big-busted women dressed up as hotel maids and naughty nurses, and admires libertine sexuality within a stifling and oppressive puritan culture. And the fantastic fornicating women in his paintings gazed back – they knew we were looking, and they didn’t care.

John Currin - Patch and Pearl, 2006, Oil on canvas, 80 x 50 inches (203.2 x 127 cm) © John Currin. Photo: Robert McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian

Currin was Édouard Manet’s heir. Manet’s Olympia caused a sensation because it was a painting of a model playing the role of a prostitute. His Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe is an image of hookers and John’s caught in the woods. The naked women in Olympia and Le Déjeuner look back at us with candid attitude as we look at them, self-aware and self-confident in the exhibitionist eroticism of the moment. When Manet made these images, paintings of female nudes dominated 19th century Paris salons, and soft pornography was tolerated and encouraged when it was hidden behind the veil of classicism. Without this hypocritical veil Manet’s scandalous paintings were an open acknowledgment of lust and pointed an honest finger at the swelling pretentiousness of erotic salon nudes. Like Manet, Currin was a truth-teller. The entire feminine world is a tumbling aphrodisiac to most men, and many women joined them in enjoying Currin’s appreciation of frank, lusty sexuality – the women he painted were perfectly confident and self-assured. As much as the tidal puritan strain attempts to excuse the oppression of individual desire in the name of the good of the collective, humans love sex in all its forms.

John Currin – Thanksgiving, 2003, Oil on canvas, 68 x 52 inches (172.7 x 132.1 cm) © John Currin. Courtesy Gagosian

In 1991, Jesse Helms’ legislation preventing the National Endowment for the Arts from funding anything that might be considered obscene threw the icy water of grey fear over curators daring to consider exhibiting nudes in public galleries. A year later, in an early and chilling manifestation of suffocating cancel culture, a Village Voice review of a Currin exhibit instructed readers to "boycott this show.” In turgid press releases and marketing blurbs, uncomfortable gallery publicists wriggled and squirmed to justify Currin’s paintings, but their bosses loved the sales. And the more his high-buttoned critics hated him, the more his libertine collectors loved him. Currin’s Bea Arthur Naked, a topless portrait of the Golden Girls star which was properly criticized for exploitation, sold for $1.9 million in 2013. In 2016 his Nice ‘n Easy sold at auction for $12,007,500. Then, in 2019, the Weinstein wave rushed through Western culture like a tsunami, and its rolling power tore into painting and sculpture. Was it possible anymore to look at a painted nude, especially an erotic female nude, without drowning in issues of sexual harassment? Knowing that the male gaze wasn’t welcomed by their p.c. colleagues, gallerists hid Currin’s full and open lust behind a new veil of supposedly self-conscious satire which took the place of the drapery of classicism. An apologist marketer at Gagosian gallery excused his work by claiming that the paintings “challenge social and sexual taboos while subverting the historical linearity of artistic genres.” Art-speak notwithstanding, in a New York Times interview in September of 2019, Currin confessed that he had simply relished offending people.

John Currin - Hot Pants, 2010, Oil on canvas, 78 x 60 inches (198.1 x 152.4 cm) © John Currin. Photo: Robert McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian

When a tsunami recedes, it leaves behind miles of wreckage entangled with the corpses of the dead and the stink of rotting fish. Scattered amongst the debris of the Weinstein wave are all the pin-ups and erotic nudes and all the sculptures and paintings of naked women in art history. Swept up by the puritanical power of the establishment’s cancel-culture, Currin turned to a new subject. His paintings of emasculated men were like an apology for his earlier erotic paintings of women. These sad and insipid males were feeble, shorts-wearing specimens of the male bourgeoisie, their impotence only matched by a pathetic vulnerability, the antithesis of his super-sexual women. In The Kennedys, which is a double portrait of JFK, this apotheosis of masculine liberal authority alternately wears lederhosen, then a dress. Hot Pants is a beautifully painted picture of a weak-chinned, balding man, vainly checking the line of his loosely tied lilac scarf in an ornate mirror while his doppelgänger tailor checks the fit of the shorts of his schoolboy uniform. His bare legs poke out of high-pulled long socks. If he had more hair and held an electric guitar perhaps he’d be a lame version of Angus Young, but this prim East Coast suburbanite has no idea what a Gibson SG is, and could never belt out a head-banging power-chord. It’s hard to imagine him ever graduating to his big-boy trousers. Are these impotent caricatures really the last men standing after the Weinstein wave withdraws? It’s hard to believe that strong, sensual women could actually want men to be like these wretched creatures.

The austere activists of the new establishment applauded Currin’s apparent surrender, and hoped these paintings were the washed-up aposiopesis of his libertine career. But surely they underestimated him. He may have finished championing erotic individualism, but had he really bathed in woke water to emerge born again as a repentant male feminist when he painted these emasculated men? Color me cynical. It seems more likely that he simply found another group of people to offend, this time stirring up the choppy waters of masculinity. Nevertheless, the narrative of his paintings of people seems to have concluded. What will he paint now? It’s time for Currin’s reinvention of landscapes and interiors. Whatever he does, give thanks for Currin’s independent spirit.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page