Salvador Dalí

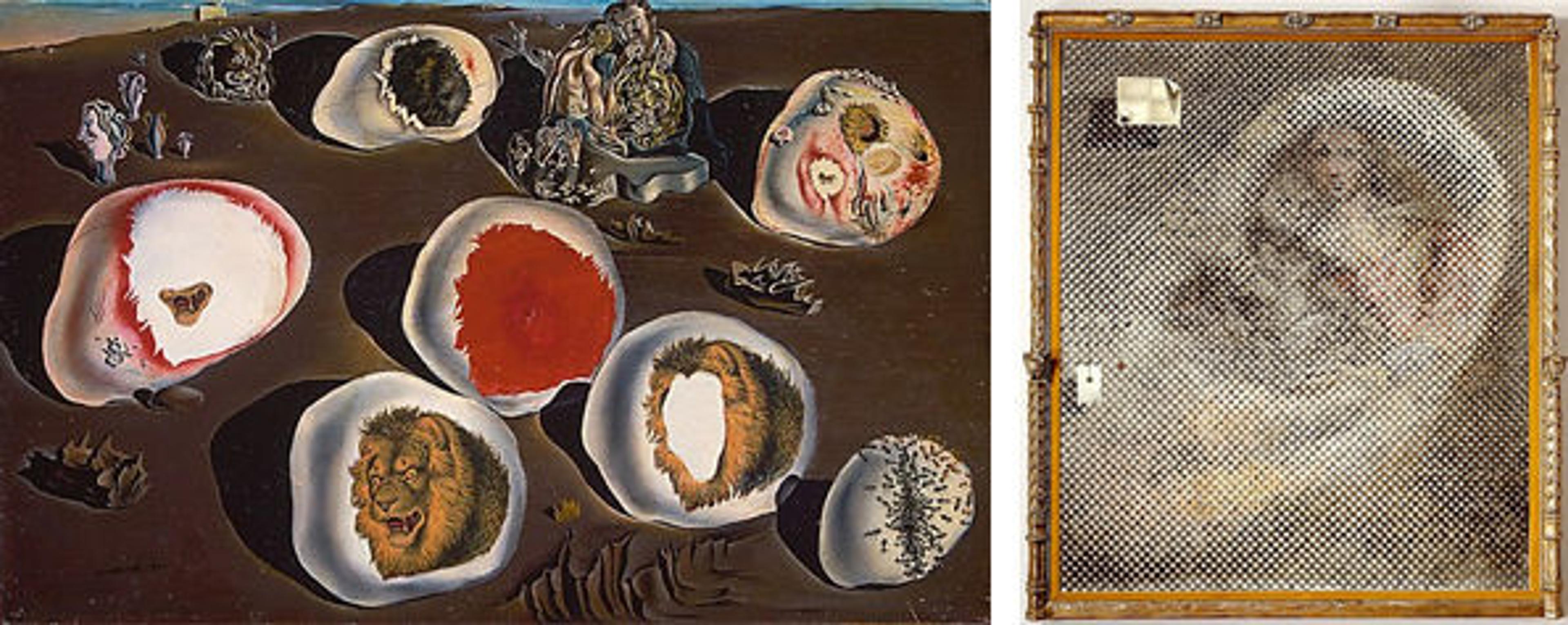

Left: Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904–1989). The Accommodations of Desire, 1929. Oil and cut-and-pasted printed paper on cardboard; 8 3/4 x 13 3/4 in. (22.2 x 34.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, 1998 (1999.363.16). Right: Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904–1989). Madonna, 1958. Oil on canvas; 88 7/8 x 75 1/4 in. (225.7 x 191.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Drue Heinz, in memory of Henry J. Heinz II, 1987 (1987.465). Both: © 2020 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society

«My family has a penchant for strolling through museums. I've appreciated this more as I've gotten older, but as a kid I got bored easily. Pausing before a piece by Salvador Dalí was always an incredible relief, and I came to crave the fluid style and disturbing clutter of his work.»

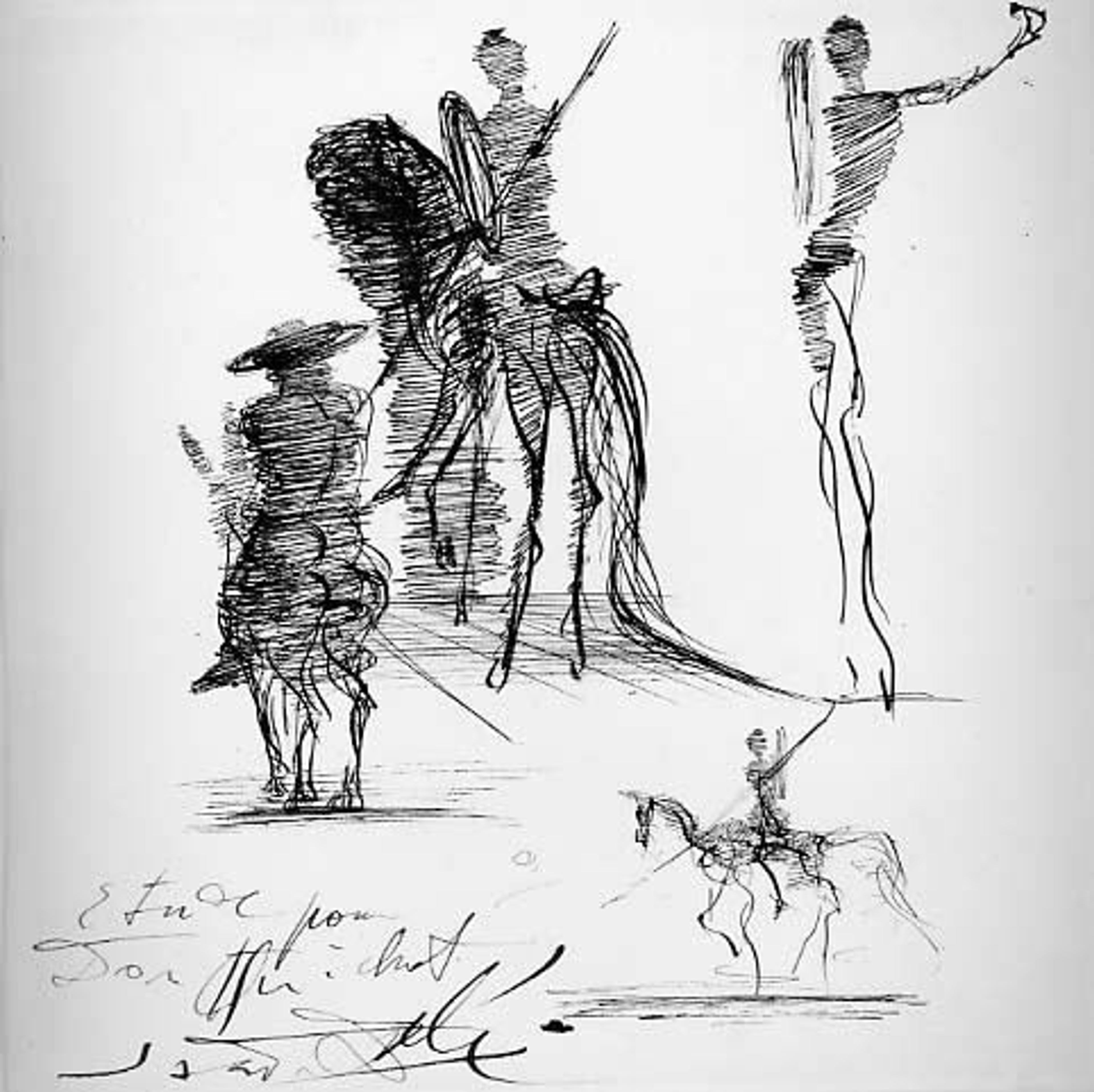

I think my interest in Dalí was first piqued by an animated film adaptation of Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes's epic novel, that I saw when I was five years old. I loved it, and even forced my grandparents to endure several re-screenings, before they showed me a few Dalí works inspired by the novel. I was enthralled. Whenever I went to the Metropolitan Museum after that, I made a beeline for Dalí's work.

Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904–1989). Study for Don Quixote, ca. 1956. Ink on paper; 7 1/8 x 7 in. (18.1 x 17.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Melinda and Alexander Liberman, 1994 (1994.591.3) © 2020 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society

Dalí became an ever-present figure in my mind. I respected him for popularizing Surrealism, but as a strange kid, I was primarily captivated by his authentic, all-around strangeness. His brilliant mustache punctuated the haze of my daydreams and became a motif in my doodles. The more I learned about his life and work, the more I felt he’d ignited a peculiar phenomenon. In creating artwork concerned with dreams, he sent real tremors along the divide of fantasy and reality.

Yet there is one Dalí painting at the Met that I never liked much until recently. In Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), Christ is suspended in front of an unfolded hypercube over a checkered floor. Dalí's wife and muse, Gala, stares up at Christ with an expression that could be awe, devotion, or religious fervor.

Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904–1989). Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), 1954. Oil on canvas; 76 1/2 x 48 3/4 in. (194.3 x 123.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The Chester Dale Collection, 1955 (55.5) © 2020 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society

The idea of a hypercube was at first incoherent to me, but I'll try to explain. A hypercube is to the cube as the cube is to the square. Extending a cube into the fourth dimension creates a hypercube. A cube has six faces, and a hypercube has eight cells (a cell is a three-dimensional component of a four-dimensional object). This painting contains an unfolded hypercube; just as you can unfold the six faces of a three-dimensional cube into two-dimensional space to create the shape of a cross, you can unfold a hypercube into a three-dimensional crucifix.

Dalí uses this projection of a four-dimensional shape in three dimensions as a literal representation of the transition of Christ from one dimension to the other. This painting, it seems, is concerned with faith and logic; it asks us to think about the nature of and relationship between God, man, and science. It captures a surreal aspect of divine geometry while maintaining a reverential atmosphere. Dalí's work is rarely as balanced and obliquely clever as Corpus Hypercubus, a painting I can finally appreciate.

See more works by Salvador Dalí in the Museum's collection.

Theo undefined

Theo is an intern with the Museum's High School Internship Program.