On September 16, Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian woman, died after being detained by Iran’s so-called morality police. Her death ignited a long-simmering anger in the people of Iran and sparked a revolution, largely led by young women, demanding an end to the Islamic regime. For the past six weeks, they’ve faced brutal government crackdowns, but they remain undaunted, adopting the Kurdish rallying cry: "Woman. Life. Freedom."

Harper’s BAZAAR has asked celebrated Iranian writers, artists, journalists, and more to help make sense of this moment when so much is at stake. Their stories are collected here, with more to come.

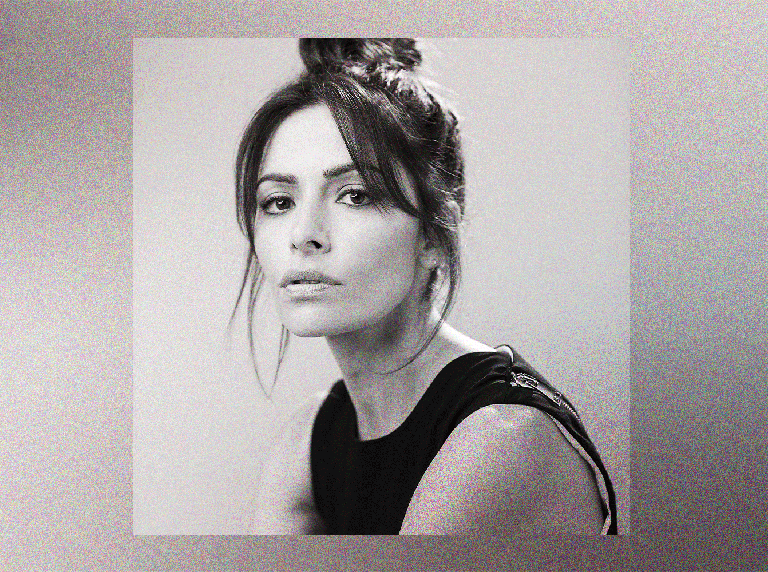

I wanted to be as American as apple pie. My parents fled Iran before I was born and settled in Texas. So it was hard for me to reconcile my identities as an Iranian American and a Texan. It was much easier to bring deep-fried Twinkies to the school fair than khoresh-e bademjoon. In the news, Iran was always represented in such a hostile way. It was the hostage crisis, it was war, it was ties to terrorism, it was the “Axis of Evil.” It was just one bad thing after another.

Nobody talked about all the beauty that came out of that country. Nobody talked about how we were at the forefront of math and medicine and art. Nobody talked about the films of Abbas Kiarostami. Jean-Luc Goddard once said, “Film begins with D.W. Griffith and ends with Abbas Kiarostami.” What about Rumi? Heard of him? He was a 13th century innovator in poetry who greatly impacted every poet that came after him.

I remember my grandparents coming to visit when I was about eight years old. We were walking through a Kmart and my grandmother was speaking to me in Farsi. I made a hard right turn and ran down a shoe aisle, putting as much distance between us as I could. I thought, “What if they think I’m a terrorist? What if they think I’m the enemy? What if they just won’t like me?” You know that clichéd move you pull when someone's talking to you and you look over your shoulder as if they’re talking to someone else? Yup, I did it, followed by an intense eye roll. I pretended I didn't know her—my own grandmother. I didn’t mean to be cruel, but when you're growing up and trying to figure out your place in the world, you don't want to stick out. You want to be “normal,” and being called by my Farsi name "Aahoo-joon" in a Kmart was anything but.

As a teen, any time I had friends come over, my mom would instantly start prepping ghormeh sabzi. "No, no, no!" I'd insist. "Just order pizza, mom! Americans love Domino's!" And she'd say, "Why would I buy pizza when I can make you pizza? It's just tomato sauce, pita bread….” Pita bread? Abort mission! “How about hamburgers? But please don’t serve maast-o khiar with the burgers. And I don't want doogh. Don't even take it out of the fridge!"

Of course, after my friends left, I’d ask my mom, "Can I have some doogh?"

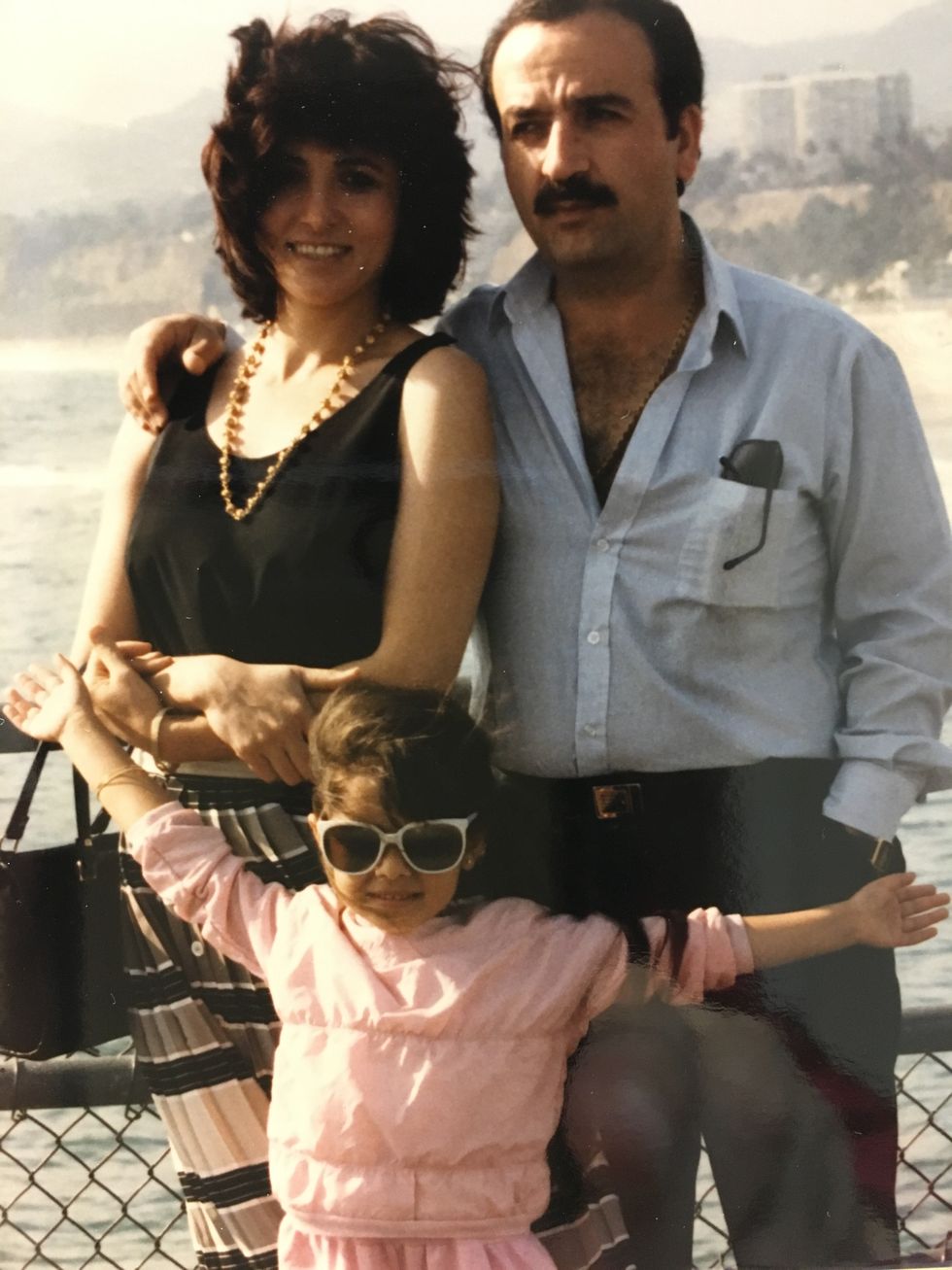

My mother fled Iran in 1978 amid the Iranian Revolution. Back then, it wasn’t mandatory to wear a hijab like it is now. But while you didn’t have to physically hide yourself, you didn’t necessarily have the freedom of expression or opinion, either.

I remember my mother told me about a friend in college who was caught reading a book that was considered anti-Shah. He was detained and his whole family was questioned. You weren’t allowed to think outside the parameters of what the government wanted you to think.

She started protesting. A mere 20 years of age. Similar in age to the many beautiful, courageous people out in the streets of Iran today. She and her friends lived in Tehran and would go out into the square to join the mass protests that were happening around the time of the Revolution. Pumping her fists, using her voice, risking her wellbeing each day for freedom of opinion and expression and prosperity. She was terrified, but that's the beauty of rebellion in youth: Even though you’re scared, you walk into your fear anyway. There was always the sense that the soldiers could just take anyone they wanted right out of the crowd. They would open fire on everybody. She watched her best friend die, shot to death in front of her—an image that haunts her to this day.

Seeing her friends die or get arrested, she felt hopeless, lost, dejected. So one night, while the city was sleeping and the raids were momentarily inactive, she fled, leaving behind the only family, comfort, and warmth she had ever known. After she left, things only got worse. The country that birthed so many wonders of the world, with a culture full of beauty and romance, was replaced by a system that believed self-expression could be punishable by death.

When I was growing up, my mother would sometimes tell me stories with gravity and sometimes toss them out casually. “Eat your spinach, and don't complain. At least you don’t have bombs falling all around you.”

My biggest challenge as a kid was getting people to pronounce my name: Aahoo Jahansouzshahi. Nobody could pronounce it. Getting ridiculed was part of my curriculum at Wilshire Elementary. I was Achoo, Yahoo, Yoo-hoo. The list went on.

“Mom, can I change my name?”

“Why? Be grateful your arms didn’t fall off in a raid.”

There was always this underlying message: “Be grateful. You have freedom. The opportunities in America are bountiful. Study hard. You can be anything you want to be. Become something.” That was the theme of my childhood.

As a child, none of my mother's stories felt real. It's hard to have an understanding of something you’ve never experienced. On September 16, 2022, that all changed for me. The death of Mahsa Amini made all those stories come alive. It was no longer something that lived in my imagination. I looked at the images, the videos, the reports coming out of Iran today, and I saw myself in them.

My DNA was tingling.

Now I know I will not be able to put my head down at night if I don't try to do something, if I don't try to honor the actions of my mother—the actions of all the women and men who are fighting for freedom and change, for those who have been fighting for it for over 43 years.

I'm a prime example of somebody who didn't fully appreciate the reality of what the people in Iran were going through because I've only ever lived an American way of life, and the only reason I snapped to attention is because I had been hearing stories like Mahsa Amini’s since I was growing up. But how do we get people who are not Iranian to relate to these stories?

I don't know the answer. I just know we have to keep the protests front and center. We need to put the pressure on the media to report what's happening. Masih Alinejad is an incredible Iranian who is at the forefront of reporting these atrocities. Please look her up and follow her on Instagram. Listen to the Iranian women who are speaking up. Learn from them and support them and amplify them.

You have to reach the point where the story feels familiar. Then you see that this isn’t just an Iranian issue, but a human issue. Then you get angry. But how are we, women in the Western world, going to relate? Well, let’s take something as common as divorce. Women around the world have initiated the end of a marriage. This is a right we have, and it's not always pretty, but it allows us to choose the direction our own lives. Now, imagine that your husband can divorce you whenever he wants, on any grounds he pleases. But in most cases, you must get your husband's approval to divorce him. And if he refuses, you must rely on an Islamic judge to compel him. If he can't be compelled, you need the judge's permission, which maybe, maybe, he'll give you. At no point is the choice over the direction of your own life yours. Are you angry yet?

You see, this isn’t just an Iranian issue, but a human issue. So take the time to understand who the people of Iran really are, so they can't be reduced to a political issue, a headline you can ignore. My people are beautiful. They’re warm and loving. They can introduce you to things—things my mother introduced to me, that I now cherish—like music and art and films and food and belly dancing.

That’s the Iran I want you to see. That's the Iran that the people of Iran want you to see. They want nothing but the same freedoms of expression that we have taken for granted.

The women of Iran are imploring you to be curious, to investigate, to help as they fight for basic human rights. I’m not sure how much power one voice, or 50, or 5,000 will have. But I know that using mine for Iranian women means using it for women everywhere. I come as one, but I stand as many. I invite you to stand with me.