JOANA VASCONCELOS

*Featured photo: JoanaVasconcelos_CoraçãoIndependente2016_ LV-AJV © Luís Vasconcelos | Atelier Joana Vasconcelo

Joana Vasconcelos is an internationally renowned artist whose popularity makes any introduction superfluous. Portuguese, born in 1971, her works have been exhibited across continents and are part of prestigious permanent collections.

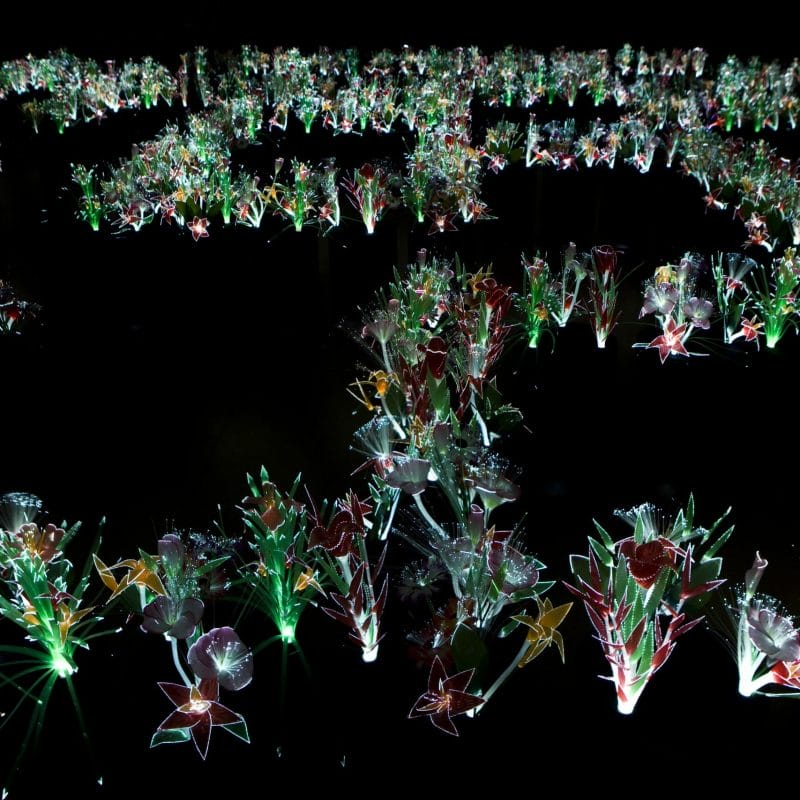

Using everyday objects, reworked and recontextualised, transformed into monumental sculptures with a touch of irony, Vasconcelos creates a bridge between the domestic environment and the public realm, addressing issues concerning the condition of women, collective identity and hyper-consumerism.

Her participation in the Venice Biennale in 2005 established her work on the international art scene. She later returned to the Lagoon event with Portugal’s floating pavilion in 2013. Vasconcelos was the youngest artist – and the only woman – to have an exhibition at Versailles Palace. In 2018, the Guggenheim Bilbao dedicated to her a major anthological exhibition.

Familiar shapes, composed of everyday objects, are decontextualised and recontextualised with a different function and, above all, are definitely of macro dimensions. Where does the gigantism of your works come from, and what is its meaning? Is it more assertive or provocative?

I would define my art as inquisitive, challenging, joyful and communicative. The large scale of my works comes quite often from my choice of materials. I start from a small, ordinary object, which, through juxtaposition, ends up creating a new, larger form. For instance, the shoe “Marilyn” gets its shape from the pans used, the average size in Portuguese kitchens, commonly used to cook rice for a family of four. In the end, the multiplication of the material culminates in its scale. It is not always a purpose that I have in mind to start off with, but it turns out that way.

Another good example is the dimension of the Valkyries as a result of the space which they will inhabit. Like Valkyrie Octopus – conceived for MGM Macau – created as a piece that should have a natural presence in location but also not loose itself among the 1,000 square meter area that it occupies. So, the scale emerges from the materials used to work a certain idea.

Yet I am, in fact, very interested in exploring the whole potential that a space and/or environment can offer, but it’s also important to have in mind that the scale of my works is quite diverse. There are many important series within my work that contemplate large and small scale works.

The scale does not have a magical ability by itself; it relies on many different components coming together. The main thing, to me, is the ability of an artwork to communicate. We try to rationalise and understand the process behind things, but the most important thing is the connection it establishes with the public. Not just in the sense of stimulating intellectually but also in creating a liaison and allowing people to enjoy themselves. The main thing is its ability to broaden our horizons and allow us to re-interpret reality. The process in itself – sketches, materials, production stages – varies tremendously from one artwork to the next, but it never replaces the final result, ever. We should not over-rationalise art so much. We should enjoy it more.

To what extent are your works feminine, and how feminist are they? And which do you think is the most feminist or the most feminine?

I am a feminist, yes, but I am interested in feminism from the standpoint of human rights and equality among individuals. My grandmother greatly influenced my life and led me to believe we have to fight against stereotypes. She wanted to be a painter but during the 1950s, women could not be artists or study art in university – girls were expected to marry young, have children and look after the family. It was what society expected them to do, so that’s what my grandmother did. Even nowadays, in some parts of the world, women still do not have the freedom to chase their dreams.

When I told my grandmother I wanted to become an artist, she encouraged me. If she hadn’t helped me understand the importance of being critical about reality and that, sometimes, traditional gender norms need to be broken, maybe I would have never gotten where I am today. I have been the first woman to do a lot of things and have witnessed others doing a lot for the first time: my first participation in the Venice Biennale, in 2005, was the first to be curated by women in its 110 years of history; in 2012, I was the first woman and youngest artist to have a solo exhibition at the Chatêau de Versailles; in 2018, I was the first Portuguese woman to have an individual exhibition at a Guggenheim.

It’s the year 2022, I am 50 years old, and it bewilders me that I have been the first to do so many of these things. There have been so many other great women artists before me, and they were not recognised for their work. It feels like both a privilege and a responsibility.

However, I don’t see it as an opportunity to self-congratulate. I’m left wondering why the other women before me weren’t given that chance, and I realise the work that needs to be done before men and women are treated equally in the art world. I know that if I were a man, perhaps I could have achieved other accomplishments, or some situations might have been easier. The male dominance of the art world goes even to the extent that some materials – such as iron or wood – are considered noble enough for art creation and others – such as textile or embroidery – are not. Being a woman artist is as hard as being a woman in any other field because we still live very much in a «man’s world». But we have progressed very fast in the past century, so I’m confident about the near future.

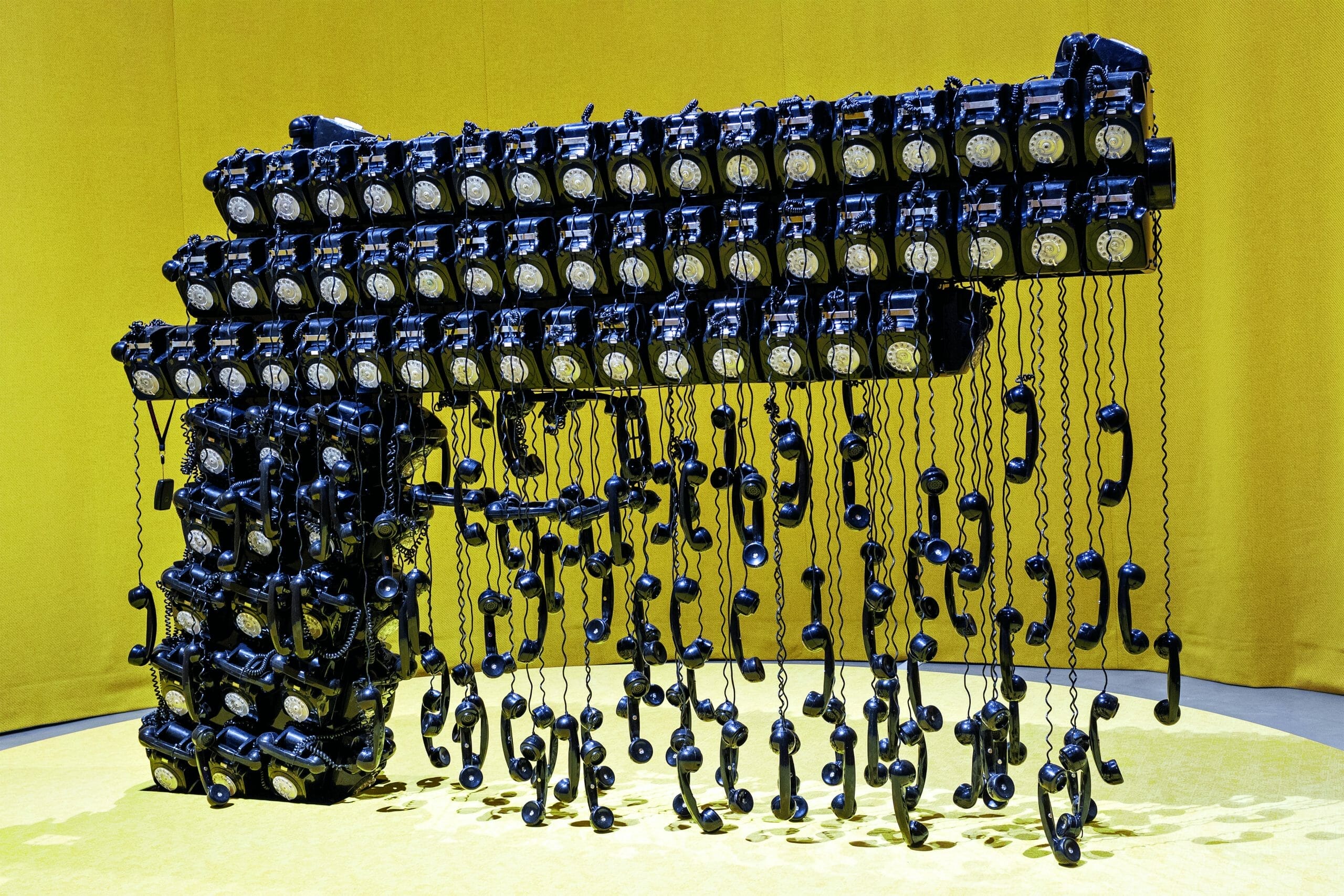

My work is essentially about breaking barriers, and the feminine tone is there because I am a woman and that conditions my perspective. I believe the value of my pieces resides within being open enough to generate various and different readings. I don’t mean to prescribe a specific meaning to my artworks. What I really want is to confront people with a critical view that makes them question themselves about what surrounds them. I mean for my works to be inquisitive and broaden people’s perspectives. I select household objects – it might be an iron, a telephone, or a pan – and then I bring them into a new dimension. It’s like the metamorphism of women themselves. If women’s traditional role as housewives has been transformed, I must also transform the house itself.

The choice of colours, some traditional materials, and techniques such as crochet speak of a global artist whose works always recall Portugal. How much and in which way do your cultural roots influence your research and your work? How would you define identity?

Being Portuguese brings many layers with it. The geography, the lifestyle, the history, the multiculturalism and the way we bring things together, all the collective references that we share as a people. That’s what makes our culture. And then there are some particular things such as the light. In Portugal, the light has a strong white quality, and that has a deep impact in our chromatic spectrum, in the way we relate to colour, which is very different from the north of Europe, for instance. And that is reflected in the choice of colours used in my work. Also, the colourfulness contradicts a few stereotyped notions and commonplaces that resulted from the four-decade-long dictatorship that Portugal went through.

There is this heavy image of a country loaded with negativity, where women dressed in black and all there was left was Fado and nostalgia. The colours in my work not only result from the juxtaposition of many different objects and symbols of a wide variety of origins but also suggest a greater sense of openness to the world. So, Portuguese traditions and the use of local aspects can often function as starting points for my work, but I’m more focused on showing how these are able to communicate beyond my surroundings. They are starting points for addressing issues that are universal.

When did you realise that you would become an artist? What was your first artwork?

To be an artist is to take on a very special and free way of relating to the world. Realising that I would become an artist wasn’t a decision but something that happened (and that I embraced). I continue to do my best every day as an answer to this calling. To begin with, I was lucky to be born into a family with a great passion for culture; I was exposed to art since I was born and encouraged to pursue it. Throughout my youth, I never really thought of becoming an artist, I considered many options, and experimented different areas such as jewelry and design. Curiously, I ended up doing sculpture. But it was a process. I was searching for my path, and in that search, I ended up finding my own direction. It was never something I decided. It happened. But discovering that I could make a living from my artistic activity only happened in 1996 when I sold my first artwork, Flores do Meu Desejo.

Your sculptures have been exhibited in very different contexts, some of them – for instance, the Palace of Versailles – with a strong personality. What are the challenges of relating to different spaces for large-scale works like yours? What relationship do you want to establish between your artworks and the site that houses them?

My work is mainly influenced by a critical observation of the reality surrounding me – it questions how we relate to the world. I’m really interested in the behaviours of contemporary society, in the everyday objects we surround ourselves with and what they mean. So, it’s very important that my work interacts and dialogues not only with the public but also with the places where it is exhibited. In fact, one of the defining characteristics of my work is its ability to dialogue with the location where it is presented, always aiming to explore the full potential that a space, its architecture and atmosphere has to offer. The framing that architecture can give to the artworks is always important and inspires me tremendously.

In a way, the location informs my art, be it the rich contexts such as the Palazzo Grassi or the Palazzo Nani Bernardo Lucheschi in Venice, the Belém Tower in Lisbon, the D. Luís Bridge in Porto and, of course, in the Palace of Versailles. Versailles was one of the biggest challenges in my career to date. To exhibit in such an extraordinary setting and to be able to communicate to such a vast international public is incredible for any artist. But I am always happy to experiment with different locations, such as Mimmo Scognamiglio in Milan, creating a really intimate exhibition with Stupid Furniture, the first to come out of the confinement due to the pandemic. Or creating the central piece for Interazione Napoli, a big Flaming Heart in the centre of the cloister, for an impressive collective show that brought contemporary art to a historic building. Or installing The Crown in Siracusa, in a dialogue with the architectural pieces of the archaeological museum and a 5,000 year-old Cycladic idol, another amazing experience.

Your work has led you to experiment with collaborations outside contemporary art – fashion, design and architecture. What of these experiences did you feel most closely related to you?

Collaboration between artists and the market is as old as the history of art and contributes to the livelihood of painters, sculptors or artisans. It’s a natural link with a cultural, social and economic expression. Throughout my career, I have had the privilege of taking on very interesting challenges such as designing a pavilion for Swatch in Venice, creating stamps for the Portuguese post or a bag for Dior, for instance. I have worked with Roche Bobois, Toyota and Louis Vuitton. And many other Portuguese brands or the partnerships that I regularly incorporate into my work, such as Bordallo Pinheiro and Viúva Lamego. I see each project as a new opportunity to explore techniques, materials or concepts. The most important thing is that I identify with the values of the brand. Not so long ago I joined Stella McCartney’s Zero Waste campaign. I met Stella in an opening of mine in 2015 in London and I identified from the very beginning not only with her fashion creations’ exquisite taste but also with her values on behalf of tradition, manual know-how, respect for materials, recycling practice and the defence of the planet. In the end, each experience is different from the previous one, but the result of what we build together is uplifting, and I am always ready for a new challenge!

What is, in your opinion, the relationship between artist, artwork and viewer?

I have shown my work in a wide variety of countries and cultures, and I have been very fortunate with regards to the way the different publics have received it. It’s very interesting to see the variety of reactions and how differently people engage with the work, depending on their cultural background. More than a mere recipient, the public plays an important active role in the discourses surrounding my work. It’s very interesting to see the different ways in which people engage with it and how diverse their reactions and perceptions of the same work can be. Normally, there is a first look, capturing the physicality of the work, in which the public is compelled to explore its surface, materials, colors and textures, and then a deeper look, activated by the tensions and dichotomies that inhabit my sculptures and raise a number of questions. Some artists like to explain their work or try to frame it but I prefer not to. I find it more interesting to allow for the artworks to create a relashionship that is open to interpretation, allowing for different readings and analysis. That it’s richness.

How do your works come into being? Inspiration, development, materials, techniques: is it more of an instinctive process, or is it a carefully planned one?

My main source of inspiration is life: symbols, objects we surround ourselves with, and the behaviour of societies over time. What is transversal in my work is the re-presenting and subverting of all this in order to generate new discourses and perspectives on reality. I decontextualise objects from a given environment and contextualise them in another space and time, subverting their meaning and thus expanding their field of interpretation. The familiar becomes something new.

Different works will bring on different challenges but I would say it is both instinctive and planned in detail. The process begins with an idea/concept, which is sketched in my notebook. Then it is transformed into a project and approached by the different teams in my studio. My way of being an artist is, perhaps, closer to artists such as Rubens or Velásquez, whose studios were made up of teams of specialists in different techniques, while nowadays, the position of the artist is closely linked to the idea of a solitary personality, which isolates from the world in order to create. At the moment, I have circa 50 people working with me on a daily basis to make sure the process goes from beginning to end. My work would not be possible without careful planning and the effort of my whole team.

Success after success, you have achieved great goals. But is there a dream you still have yet to realise?

My goal is to keep working and to do my job well. I have a huge desire to live and continue to create. I still have many dreams to realise, but one, in particular, is to open my studio to the community and to the world, turning it into a workshop and a museum simultaneously. I have started developing this project; it will happen by the river in Lisbon and will be called “Atelier Museu Aberto”.