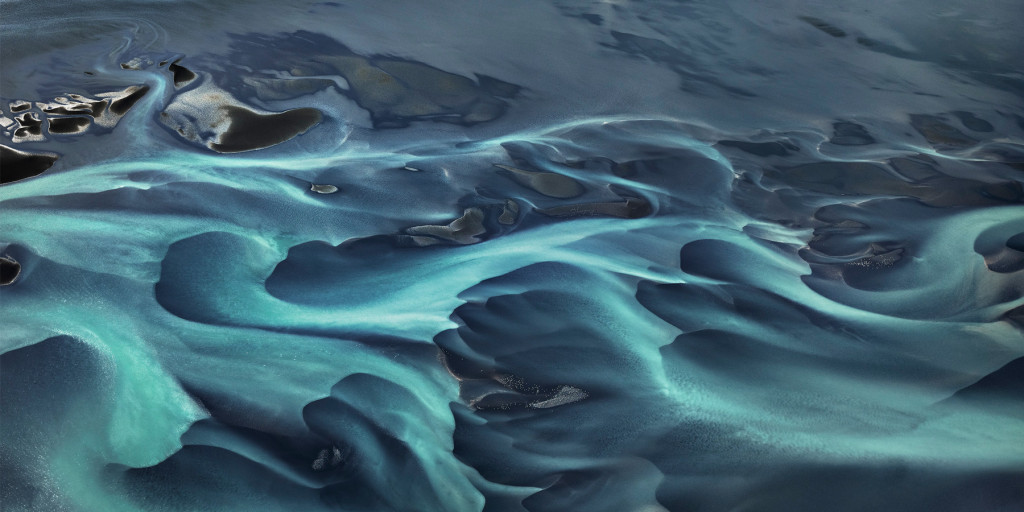

April 4, 2016Photographer Edward Burtynsky — the subject of the show “Water,” currently at Norfolk, Virginia’s Chrysler Museum of Art — has been making images that capture the intersection of the natural and industrial worlds for more than 30 years (portrait by Birgit Kleber). Top: Ölfusá River #1, Iceland, 2012. All photos © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto; Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York; and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York, unless otherwise noted

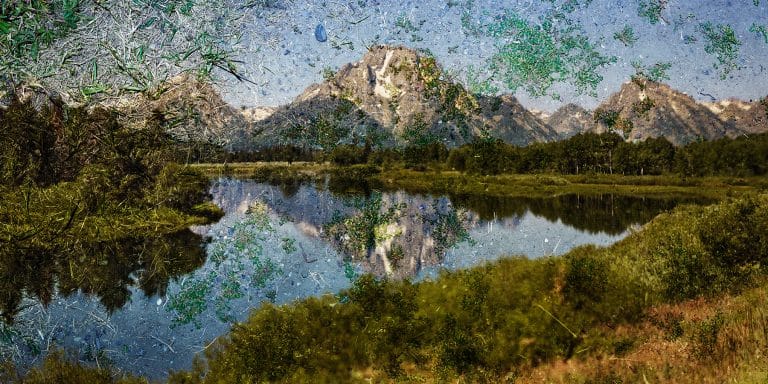

Through his images of open-pit mines, railroads, oil rigs and the like, the Canadian-born photographer Edward Burtynsky examines how humans interact with the natural world. But because he shoots from a distance, the bold shapes and colors of his work are often strikingly reminiscent of those found in paintings by Richard Diebenkorn or Jean Dubuffet. The photos, many of them bird’s-eye views, are as much about form and hue as they are about their subject matter.

“They’re so beautiful. You say, ‘Wow!’ And then you say, ‘What is that?’ ” observes Erik Neil, director of the Chrysler Museum of Art, in Norfolk, Virginia, where more than 60 of the photographer’s large-scale images are on display through May 15 in the exhibition “Edward Burtynsky: Water.”

Burtynsky was born in St. Catharines, Ontario, in 1955 and began playing with cameras at age 11. As a child, he was fascinated by his town’s imposing General Motors plant, where his father worked, and he credits the factory with awakening his interest in industrial sites, which he would photograph years later. Burtynsky went on to study photography at Ontario’s Ryerson University and later founded Toronto Image Works, a photography training center and lab.

His interest in industrial activity and landscapes led him to photograph quarries, recycling yards, woods, marshes, rural communities, dams and factories, among other locales. For the past 30 years, he has used photography to explore “ever-expanding human systems imposed on a landscape,” as he has put it. Burtynsky — who is represented by such top dealers as Rena Bransten Projects, in San Francisco, and Howard Greenberg Gallery, in New York — has been known to wait months for the right weather and lighting conditions in which to capture his images, which he manipulates only minimally post-shoot. He often photographs from a helicopter, and he experimented with drones long before they became popular for aerial photography. By using cutting-edge digital cameras that take super-high-resolution images, Burtynsky can print his pictures on a monumental scale: Many of his works measure 48 inches by 60 inches.

Water has always been a theme running through Burtynsky’s nature-focused work, but the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico compelled him to look specifically at bodies of water around the world and how humans live with these vital natural resources. “While trying to accommodate the growing needs of an expanding and very thirsty civilization, we are reshaping the Earth in colossal ways,” he wrote in his artist statement for the “Water” show. “We are also capable of engineering our own demise. My hope is that these pictures will stimulate a process of thinking about something essential to our survival.”

Burtynsky has been known to wait months for the right weather and lighting conditions in which to capture his images.

On view through May 15, the show at the Chrysler Museum of Art includes more than 60 of Burtynsky’s large-format photographs. Photo by Ed Pollard, courtesy of the Chrysler Museum of Art

The land- and waterscapes included in the Norfolk show range from the thoroughly industrial — the Deepwater disaster, for example, and a geothermal power station — to glaciers and rivers where human intervention is less obvious. With his photographs, Burtynsky shows how land can be tamed and elegantly shaped through agriculture and other means of control: An image from Texas of pivot irrigation (better known as “crop circles”) looks like a neat series of perfectly round clocks. (“That minimalism really reminds me of Diebenkorn,” Neil says.) A stone stepwell in India, meanwhile, is menacingly geometric.

Some photos feature the impact of water (or lack thereof) on infrastructure. In one, we see a road that separates the utterly dry landscape of an American Indian reservation from that of a well-watered Arizona suburb. In another, we get a glimpse of Verona Walk, a mazelike community of waterfront properties and covered pools that was built on a canal-crossed swamp in Naples, Florida.

“From afar, you see the folly of building in certain places,” Neil says. He found the photographs particularly relevant to Norfolk, a city that flourished because of its port and where residents are “very concerned about rising sea levels.” Driving the message home even further, the exhibition originated in 2013 in New Orleans, another city where water has been both blessing and curse.

Overall, Burtynsky’s work avoids harsh judgments, leaving room for questions as well as aesthetic enjoyment. “Water is a vast subject, but Ed has picked certain aspects that are relevant to our lives right now,” says Jenny Baie, a director at Rena Bransten Projects. “In some of the images, sustainable things are happening, while in others, something problematic is going on. He’s not an activist or a conservationist, per se, but he calls attention to important issues through the sheer beauty of his photographs.”

Shop Edward Burtynsky on 1stdibs