Blog

January 21, 2020

What happened after the evacuation and liberation of Auschwitz?

By Emeritus Professor Konrad Kwiet, Resident Historian

Not long ago, Helen Tichauer passed away in New York, aged 100. She was one of the first Jewish women to enter – and one of the last to leave – the living hell of Auschwitz. She arrived on 28 March 1942, and she was ordered to close and to lock the iron gate of the women’s camp when she departed on 17 January 1945, the day when the death march of 65 000 inmates commenced. On 27 January 1945, Russian soldiers liberated 4,800 inmates from Auschwitz. The day has been chosen by the United Nations as International Holocaust Remembrance Day. But what is far less known – what happened after the evacuation and liberation of Auschwitz?

As the Allied forces were approaching Germany, orders were given to evacuate concentration camps and to erase the evidence of the horrific crimes perpetrated. No inmate was to fall into the hands of the Allies. They were still required as slave labour.

In early January 1945, more than 720,000 people from all over Europe were still incarcerated in concentration camps; one third were Jews. From the outset, the evacuations turned into death marches, unfolding in full public view. About 250,000 men, women and children perished on route. Some 15,000 Auschwitz prisoners did not survive the final phase of the German genocide unleashed in the last chaotic weeks of the war and the collapsing Nazi regime.

Lined-up, divided into rows, the exhausted and emaciated prisoners were marched on foot and in freezing temperatures to the city of Gleiwitz. If they could not keep up, they were shot or beaten to death by guards. Others died of starvation or froze to death. After a short, horrific stopover in Gleiwitz, they were loaded onto open freight trains and transported to other detention facilities located within Germany. As it happened, at railway stations in occupied Czechoslovakia, locals greeted the deportees and threw food into the wagons. As also happened in other places, some Germans did not hesitate to kill Jews on death marches. Intoxicated by Jew-hatred and, since 1939, accustomed to murder, they feared that survivors could not only testify in courts to the crimes committed but also seek revenge.

Some 60,000 survivors of death marches were liberated at railway tracks and along roads, in fields and forests, in barns and stables, in houses and factories and in overcrowded and disease-ridden concentration camps. At the time they were classified as Sh’erit Ha-pletah, the remnants of European Jewry. In general, they were young and single. Assembled and registered in Displaced Person Camps, they started to search for missing relatives and friends and prepare their next journey to new homelands, where they hoped to rebuild their shattered lives. Wherever fate took them, they were accompanied by memories of traumatic experiences: they bore scars which never fully healed.

Liberated concentration camp prisoners at Bergen-Belsen mingling with their liberators. Photograph by Lieutenant Alan Moore. SJM Collection.

Holocaust survivors greeted their liberators with joy and tears of gratitude. Yet exhaustion and sickness had rendered many of them close to death — mute, immobile and indifferent to their surroundings. In Bergen-Belsen almost 15,000 inmates died in the days following liberation, despite the best efforts of medical personnel.

The film footage taken at the time of liberation made international headlines. The liberation of Bergen Belsen in April 1945 became an iconic image of the Holocaust for the Western world. Olga Horak survived Auschwitz and Bergen Belsen, aged 18, weighing a mere 29kg, suffering from typhus and diphtheria. She rebuilt a life, a happy life in Australia. She still tells her story of survival at the Sydney Jewish Museum.

Death, disease and horror remained rampant after the liberation of Auschwitz. Russian soldiers and Polish relief workers never forgot what they saw. While Soviet authorities took over the administration of the three Auschwitz camps and distributed food to the survivors, a Polish team of 38 volunteers dispensed medical and nursing care. Recruited by the Polish Red Cross, 8 doctors, 13 nurses and 17 paramedics arrived on 5 February. They faced a mammoth task.

Liberation of the children’s ‘block in Buchenwald concentration camp on 25 May 1945. Photograph by Byron Rollins. USHMM, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park.

Lists were compiled, registering the names and numbers of survivors. 2,200 were found in Auschwitz II (Birkenau); 1,800 in Auschwitz I (Stammlager); and 800 in Auschwitz III (Monowitz). More than 2,000 had died after the evacuation. Everywhere – in barracks and bunk beds, at fences and walls or in other open places, lay frozen corpses surrounded by waste and human excrement. Body parts were laying around the destroyed gas chambers and crematoria and had to be collected and buried. Next to the dead and the dying were the prisoners suffering from malnutrition and diseases. All were severely undernourished, weighting between 25 and 35 kilograms. Many had open wounds and were frost bitten. Others were diagnosed with tuberculosis and typhoid fever. Quickly a hospital was set up in Auschwitz I to care also for patients sent from the other two camps. However, for many, medical help came too late.

The survivors of Auschwitz hastened to search for missing relatives and friends. Thousands of telegrams, postcards and letters were dispatched across the globe. Thousands of replies were received. Survivors were asked to tell their stories or to fill in questionnaires. They also presented affidavits to the Soviet war crimes commission to be used for the prosecution and punishment of Nazi killers and local collaborators. Once they were fit to travel, they were released. They received Red Cross Identity cards, a free three-day rail ticket, a dry-food ration for 3-5 days and a very small amount of money. By the end of September 1945 most survivors had left Auschwitz. On 1 October 1945 the hospital was closed.

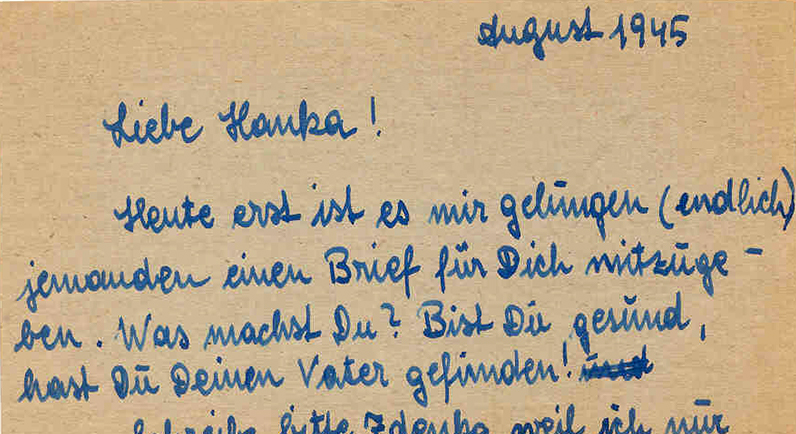

Letter from Renee Konstant in Vienna to Hanka (Hana Lipa), August 1945. She asks of news of her and Zdenka and implores her to write immediately. She writes about the death of her brothers and that she has no news of her parents. SJM Collection.

And yet, some survivors remained in Auschwitz. Young and single, uprooted and with nowhere to go, they felt obliged to secure the transformation of the murder site into a memorial site. This task included preventing the visits of grave robbers, “neighbours” who, encouraged by the myth of “Jewish money’”, were searching for coins or notes, jewellery or other valuables buried in the ground. Such incidents were not infrequent at murder sites dispersed throughout Eastern Europe.

The Polish medical and nursing team played a vital role in saving children and babies. Prior to and following evacuation, Polish, Russian and Yugoslavian women had given birth to 24 babies in Auschwitz. Aged between nine days and six weeks, they were admitted to hospital with their mothers. The overwhelming majority of them survived and enjoyed a long life. Two babies, however, could not be rescued. In addition, 80 children of different nationalities, aged between two and fourteen, were located. 56 of them were sent in mid-March to an orphanage in the near-by city of Katowice, run by the Catholic Caritas aid organisation. The group was soon brought back to Auschwitz to be filmed by the Soviet war crimes commission. Accompanied by Catholic nuns, the children were lined up and led along the barbed wire fences before being instructed to display their Auschwitz tattoo. The film footage and photos also emerged as an iconic visual testimony of the Holocaust; though no mentioning was made that they were taken a few weeks after the liberation. Only a handful of children were re-united with their parents. The majority grew up in orphanages or foster families dispersed throughout Poland, the Soviet Union and other countries.

Among the liberated children was Palko Blum, a Polish boy. He was sent with his mother in late 1944 to Auschwitz, registered and tattooed with one of the last prisoner numbers – B 13979. He later found a new home in Sydney. It was only in 1999 that he saw the film footage, photos and camp records, which served to reinforce the enduring memories of his incarceration in Auschwitz and eventual liberation.

What’s On Newsletter

Keep up to date on all Museum events and exhibitions.