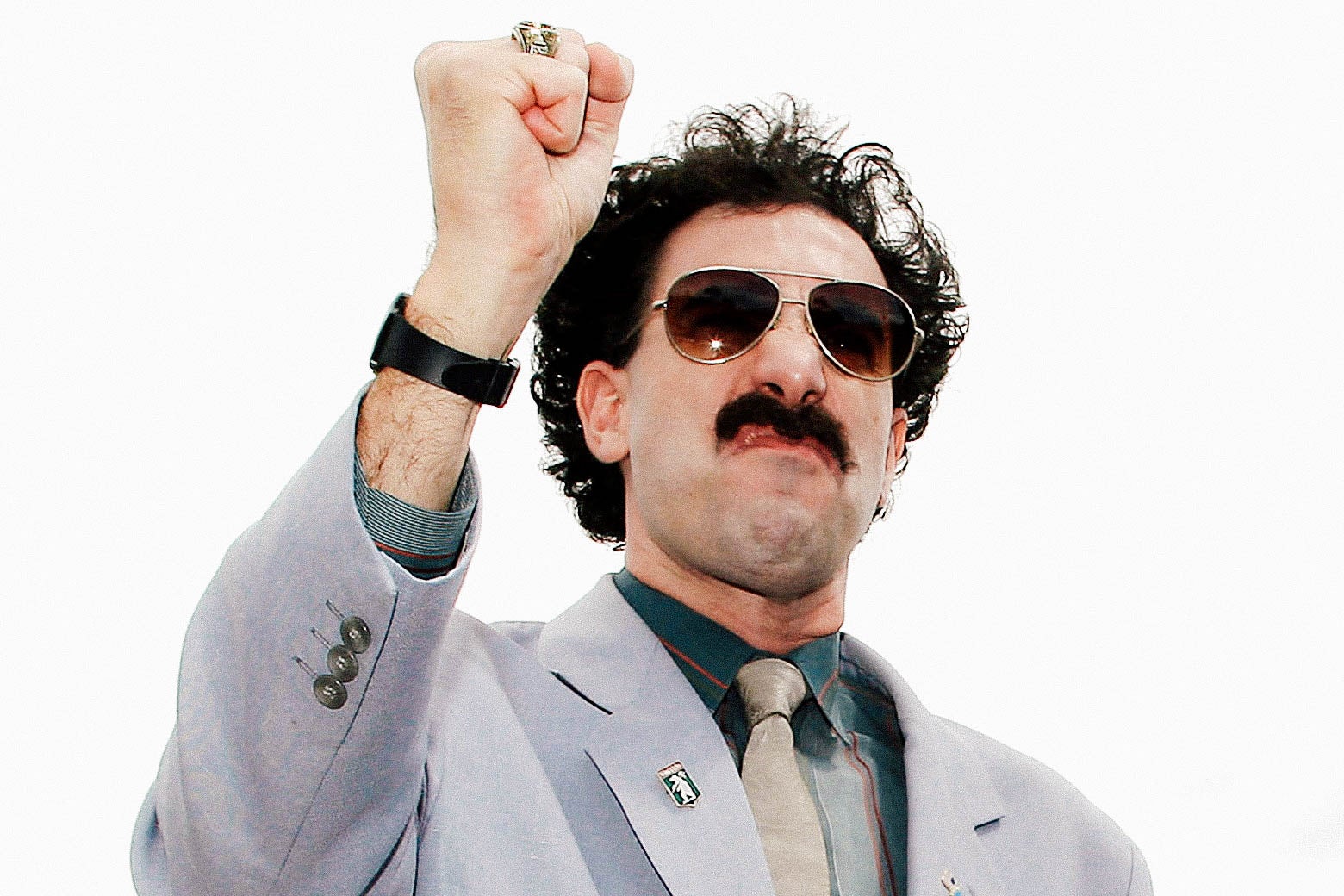

On Sunday, Sacha Baron Cohen made his moderately anticipated return to television with Showtime’s Who Is America?, his latest interview-prank series. Reviews were mixed, with critics quickly questioning the value of Baron Cohen’s approach in 2018. What new depths of the American id are left for him to unearth that haven’t already been flaunted by the president?

And yet it’s hard to fault Baron Cohen, who never found firm footing as a movie star, for returning to the format that earned him critical acclaim and box-office success. A decade before the 2016 election, the comedian arguably excavated those same national impulses. In his breakout film, released during the waning years of the George W. Bush presidency—that far-ago era when the GOP establishment proposed a bill with a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants—Baron Cohen revealed that unvarnished strains of racism, anti-Semitism, and misogyny remain alive and well in America. Some of Borat’s scenes still startle. Even by post-2016 standards of awfulness, for instance, it’s shocking to hear a frat guy “wish” for slavery’s revival. One could also argue that the extreme gullibility of Baron Cohen’s dupes—one of whom teaches the comedian’s Kazakh reporter how to wipe his own ass after he brings his fresh turds to the table in a plastic bag in the middle of a dinner party—exposes a softer kind of bigotry.

But in 2018, Borat is mostly hard to watch for punching down as much as it punches up. The movie rips into America’s rose-tinted visions of itself, but it’s also premised on the idea that there are “shithole countries” that primarily exist to bolster our own sense of national and cultural superiority. Twelve years later, we have higher standards for what counts as politically useful comedy. Borat no longer makes the cut.

The feature does remain a clever bit of vengeance. Baron Cohen, a Jewish Brit, makes a grotesquerie out of anti-Semitism while reminding viewers that it continues to thrive all over the world. (His anti-Semitic “Kazakh” speaks no actual Kazakh in the film; most of the character’s native-language dialogue is in Hebrew.) When Borat calls a black man a “genuine chocolate face” or refers to his “jar of gypsy tears to protect [him] from AIDS,” Baron Cohen and his writers underscore the backwardness of Borat’s other beliefs. And because the Kazakh is so casually vicious—he high-fives the hotel clerk who informs him that his wife has been raped and killed by a bear—Baron Cohen’s shock tactics haven’t lost their effectiveness in jolting us into remembering the ugliness and seeming randomness of hate. This project of uncovering anti-Semitism, or at least the happy acceptance thereof, was one of Borat’s main bids for social relevance. Comedy doesn’t always need to speak to the issues of the day, but Baron Cohen’s other characters—nitwit rapper Ali G, fashion reporter Brüno, The Dictator’s Qaddafi wannabe Admiral General Aladeen—have failed to take off, at least stateside, partly because they failed to deliver as many insights into our own American character. We remember Borat because he had something to say about us.

But Borat indulged our xenophobia, too. The film is largely remembered for the many scenes when we’re supposed to laugh at the (seeming) credulity of Americans as Baron Cohen rattles off outrage after outrage: Borat sleeps with his mother-in-law, offers his guest a cheese made of his wife’s breast milk, and expresses surprise that “a retard” would be allowed to eat at the same table as everyone else. But there are also plenty of scenes when Borat simply explains “Kazakh” customs to the camera or interacts with his producer Azamat (played by Ken Davitian). We learn in the longish prelude, set in Borat’s hometown (filmed in Romania), that they believe Jews sprout horns and lay eggs, while the “town rapist” is warned by Borat, “Not too much raping—only humans!” A few details like these would have sufficed for the subversion of anti-Semitism discussed above, but the gags keep piling on: Kazakhs believe women’s brains are the same size as squirrels’ brains, fear that Jews can shapeshift into cockroaches, and use pubic hair as a form of currency. It’s undeniable that Baron Cohen intends for viewers to laugh not just at American ignorance but this (heavily fictionalized) version of Kazakhstan, too.

What we’re really asked to laugh at, though, is a “shithole country.” With Borat, Baron Cohen reclaimed for “First Worlders” the “right” to mock foreigners from developing nations. Only with the Borat accent are the phrases “my wife!” and “very nice!” punchlines we all remember a dozen years later. At a time when the range of “funny voices” that white comics were “allowed” to do continued to narrow, Baron Cohen gave his permission to revel in a fading white privilege to the millions of frat boys he simultaneously mocked. It’s also worth noting that Baron Cohen keeps resuscitating that prerogative to play different variations on the monstrous foreigner—like Aladeen and now Israeli “terrorist terminator” Errad Morad, who shares views about sexual assault that are as medieval as Borat’s, claiming that “it’s not rape if it’s your wife.”

But in an era when the ruling administration’s single most vile act hinges on the dehumanization of outsiders, it’s hard to laugh as a white comedian takes potshots at a “shithole country” for 86 minutes while exploiting stereotypes about the poor and uneducated. After all, Baron Cohen’s view of Borat isn’t too dissimilar from how white nationalists here and in Europe view immigrants and refugees: ignorant, violent, prone to sexual assault, unable or unwilling to assimilate. (Borat says he wants “cultural learnings” of America, but much of his behavior involves ignoring obvious social cues to comport how he would at home.) I’ll cop to laughing at Borat upon the film’s release, but as a foreign-born American and the child of immigrants, I’m sure I saw myself as the “good” kind of foreigner and Borat as the “bad.” Now, that kind of parsing is being deployed to separate families and ban immigration from certain countries (especially majority-Muslim countries—of which Kazakhstan, in real life, is one). Twelve years later, Borat continues to illuminate. But now what it lays bare is the xenophobia we were willing to embrace while pointing fingers at the bigots on-screen.