This is a guest post for Silent London by Sabina Stent. Sabina has a PhD in French studies from the University of Birmingham and is a regular contributor to Zero magazine. Her PhD thesis was on Women Surrealists: sexuality, fetish, femininity and female surrealism – and you can read it in full here. This article is an edited extract from her thesis, focusing on the early cinema of Luis Buñuel.

There are particular images that were central to the Surrealist movement. The human hand, for example, became a frequent Surrealist motif and can be seen in the movement’s films, paintings and photography. Why were these motifs so important to Surrealism and why do we continue to discuss them as part of the movement’s history? To understand why we must look to the Surrealist films of the 1920s, specifically Un chien andalou (Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel, 1928) and L’Age d’Or (Buñuel, 1930) and how key scenes emphasised the reoccurring themes that were so central to this movement.

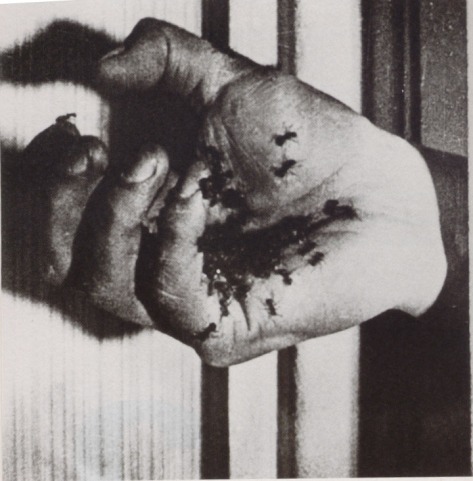

The repetition of hands in Un chien andalou is, to put it simply, a symbol of fetish: what hands can do and how they can generate both intense pleasure and intolerable pain. Williams has commented that ‘the function of the fetish arises from the fear of castration’ and can only be preserved through making the object in question a symbol of fetish.[1] The repetition of wounded and severed hands in the film represents castration fear, and more specifically, a disembodied phallus. This is emphasised when we realise that all the hands, whether injured or exuding ants, are male.

Such images emphasise Freud’s notion of the castration complex and the absence of the maternal phallus in its feared symbolism. Continues Williams: ‘while the first appearance of the hole and ants emphasized the fear that women have undergone castration, the excruciation of this same hand caught in a door emphasizes the more present and direct agony of undergoing dismemberment.’[3] Dalí’s interest in hands is also evident in his independent work, which uses this part of the anatomy to great effect. Indeed, according to Short, an initial idea for a scene in L’Age d’Or was based on a Dalí drawing ‘of the man kissing the tips of the woman’s fingers and ripping out her nails with his teeth’.[4] Short continues that ‘Dalí believed that ‘this element of horror’ would be ‘“much stronger than the severed eye in Un Chien Andalou”. As we have seen, Buñuel replaced the ripping out of nails with an amputee’s hand, missing fingers compensated by phallic thumb’.[5] Dali’s original idea involves the removal of anatomical matter connected to living flesh. So too in Un chien andalou the symbolic threat of castration is produced by the finger standing in for the phallus, thereby generating stronger charge than dismemberment or symbolic castration involving, say, an amputee’s false limb.

Hopkins has considered the Surrealist movement’s overtly-masculine attitudes as a reflection of male-dominated eroticism and its emphasis on the female body.[6] With reference to the Oedipus complex, he comments that ‘the fetish thus stands in for the missing maternal phallus and symbolically allays the reminder of castration evoked by the sight of female genitalia.’[7] This implies that the woman, ‘lacking’ a penis, requires a substitute for the organ, something she achieves through a focus on her other body parts or through the use of props placed upon the body. Such conceptions are almost universally condemned by feminist critics as degrading theoretical props to objectification, as Hopkins writes:

Female commentators have justifiably argued that women’s bodies, and by extension, femininity, are often demeaned via the objectification and fetishisation visited on the female body in the service of male psychological ‘liberation’, and Surrealism in particular has comparatively little to offer in the way of a counterbalancing female viewpoint.[8]

The castration, or dismemberment, of a limb may be identified with acts of violence, and comparisons made to sadomasochism, especially as the body usually belongs to a woman. Here we must question what makes pain and pleasure operate in this instance. This is because, as the depicted wound or severed arm is never shown to bleed, it heightens the surrealist, disjointed and, above all, symbolic nature of the image as well as the movement’s dreamlike imagery. According to Malt,

Just as in the case of fetish, the present object connotes the absent trauma, and it is significant that the trauma of amputation or truncation which the body so often undergoes in surrealist imagery is always in some sense absent, for it has occurred in a body that is always already a representation.[9]

While Un chien andalou offers representations of castration, any similarities that occur within L’Age d’Or are placed within a slightly different context, instead focusing on the theme of masturbation. Evoking sexualised depictions of desire, Williams writes that L’Age d’Or’s ‘first suggestion of masturbation occurs when the female hand of the hand-cream ad comes alive and begins rubbing the black cloth of the background with two fingers’.[10] This is exactly why hands are a prominent symbol of fetish; they have the potential to produce both pleasure and pain in intense forms. As a body part, the hand is essentially responsible for masturbation, and this forms the basis of its highly suggestive function and connotations in much Surrealist art. In Un chien andalou, for example, the various hands are representative of ‘psychic infestation’,[11] evoking an almost fidgety sensation that is comparable to erotic bodily desire and an impatient yearning for sexual intercourse. With reference to Un chien andalou, and theories of masturbation, Short comments that

The ants-in-the-hand shot doesn’t just reprise the guilty, masturbating hands – similarly enlarged, similarly ‘severed’ at the wrist – in Dalí’s paintings of the time. It also illustrates the French phrase for pins and needles – “avoir des fourmis (dans la main)”, which doubles for “feeling randy”. And the repeated composition of close-ups in which the frame cuts off a hand at the wrist evokes the age-old paternal threat to sons found masturbating.[12]

This threat to ‘sons’ described by Short is intriguing, implying that the feminine hand poses a threat to males by alluding to myths of masturbation. Amongst these include the age-old social stigma of young boys being told by adults that, if found masturbating, they will have their hands chopped off. For the male, the loss of a hand may essentially be compared to the loss of their phallus, resulting in the child’s innate fear of castration through the threat of this absence. As has been demonstrated, masturbation as a sinful activity for young boys later manifests itself as a symbol of sexual desire within Surrealism. In L’Age d’Or fingers are frequently encased in bandages as though injured. This is significant, as Short indicates: ‘fingers are bandaged because “bander” also means “to feel randy”. The girl’s ring finger bandaged alternates with the same unbandaged: horniness with detumesence’.[13]

Dalí may have considered the eye-cutting scene in Un chien andalou less effective for reasons connected to hands and fetishism. Although still horrifying, the scene poses less of a symbolic and sexual threat than hands, especially because eyes less commonly denote a fetish.

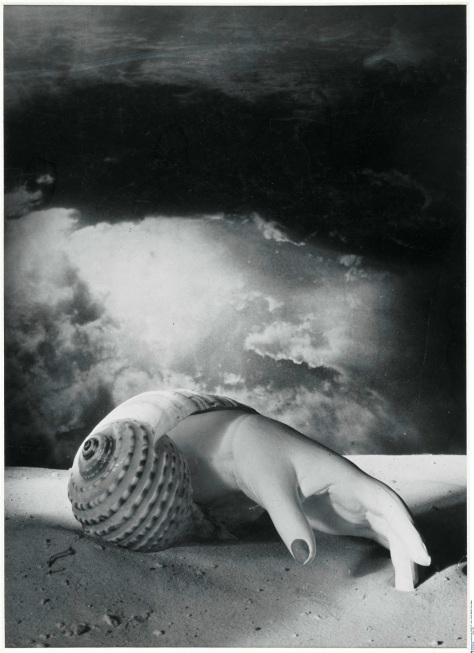

Somewhat surprisingly, given the movement’s tendency to be thought of as highly patriarchal and misogynistic, female Surrealists used similar imagery in their work. Hands frequently appear in the photographs of Lee Miller and Dora Maar as they teased the viewer with their art, allowing multi-faceted readings of their work and creating the opportunity for women artists to achieve creative freedom and cast away sexual inhibitions.

Un chien andalou and L’Age d’Or may contain scenes threatening women and reducing them to sexual beings, but ironically, these scenes assisted the female Surrealists to reclaim their sexuality and establish their rightful place in the movement.

By Sabina Stent

[1] Linda Williams, Figures of Desire: A Theory and Analysis of Surrealist Film (Berkeley California, Oxford: University of California Press, 1992), p. 83.

[3] Williams, p. 92.

[4] Robert Short, The Age of Gold: Surrealist Cinema (UK: Creation Books, 2002), p. 154.

[5] Ibid, p. 154.

[6] David Hopkins, Dada and Surrealism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 117.

[7] Ibid, p. 121

[8] Hopkins, p. 122.

[9] Johanna Malt, Obscure Objects of Desire: Surrealism, Fetishism, and Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 138.

[10] Williams, p. 146.

[11] Short, p. 78.

[12] Ibid, p. 101.

[13] Ibid, p. 121.

good. ……