Documenting the Human Epoch

He’s photographed rare coral reefs off the coast of Komodo Island, Indonesia. He’s documented environmental destruction from the nickel mines of Sudbury to the largest ivory burn in Africa’s history. Now Edward Burtynsky wants the people of Georgian Bay to know they live in one of the most naturally beautiful places on earth. And it’s worth protecting.

By Roger Klein // Photography by Edward Burtynsky

Nickel Tailings #34,

Sudbury, Ontario, 1996

“I think we are part of nature, but we have severed that cord. Whether it’s the way we live in cities, whether it’s through religion, whether it’s through systems that we have brought in, (we’ve become) separated from being part of that natural order,” he says.

Uranium Tailings #12,

Elliot Lake,

Ontario, 1995

Alberta Oil Sands #9,

Fort McMurray,

Alberta, Canada,

2007

It’s not unusual for one of Burtynsky’s prints to sell for more than $50,000, as revealed by past lots of fine art auction houses such as Christie’s, Heffel, and Phillips. A 40” X 60” print of the mining tailings — similar to the image featured in the opening spread of this article — recently fetched $64,900 at auction.

In an exclusive interview with On The Bay at his home in the Blue Mountains, Burtynsky shared his informed perspective on the environment around Southern Georgian Bay and why it’s time to start protecting more of what makes this place special.

Burtynsky is originally from St. Catharines, Ontario, where he was born and raised, but much of his youth was spent with his father fishing and foraging around the lakes and rivers of the Canadian Shield. He got his first camera at the age of 11 and set out to photograph nature and explore Canada’s north. Burtynsky was only 15 when his father passed away. By that time they had already worked together in a darkroom to develop his early photographs.

Over the past 40 years, energy and resource extraction have been much of Burtynsky’s subject matter, which often takes place in faraway lands, out of sight and out of mind. Whether it’s the world’s largest copper mine or the destruction of rainforests in Borneo, Burtynsky brings it home and hits you in the face with it. He says an enormous amount of research and planning is required to get access to the places controlled by industry. It’s a long process that allows him to detach his emotions from what he sees on location when he has to focus on the photography.

“To me I’m less, kind of, emotional when I’m there because I’m in a state of…” His voice trails off.

Dam #6,

Three Gorges

Dam Project,

Yangtze River,

China, 2005

“I have to be, especially when I have film crews and things like that, I have to keep everything going. I have to keep everybody on track. I have to be watching the light. I have to be watching: Where do I want to stand? Where do I want to be in those precious few windows that you get to work? So, I’m one hundred and ten percent and trying to capture the place while I’m there,” he says.

Creating impactful images requires special techniques — and Burtynsky’s have evolved over the years from purist, large-format, glass plate photography to multi-exposure, digital, stitched, giga-pixel-size images, which are included in the collections of more than 60 museums around the world, enshrined in the permanent record of history.

When on display, his large high-resolution prints allow viewers to peer deeply into the details. The goal is to open our eyes and our minds to the scale of the human fingerprint.

“A lot of these things I’ve photographed are such massive landscapes. These transformed landscapes — sometimes the only way you really get to understand how big that quarry is or how big that mine is, (is) by recognition of something like a pickup truck or a barrel of oil. So this barrel in a big large print might only be about a half an inch in terms of size on the print, but it’s big enough you can make it out and you can see it in the large format. You can clearly see that’s what it is, and if you compress that into the size of a book — an 8” x 10”— chances are you’re not going to see that barrel that reveals the scale of that place.”

Beyond his own photography, Burtynsky has also collaborated with director Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier on three documentary films that confront some of the most glaring environmental issues facing humanity. That includes the impacts of mining, water pollution, plastics, deforestation, and the loss of biodiversity.

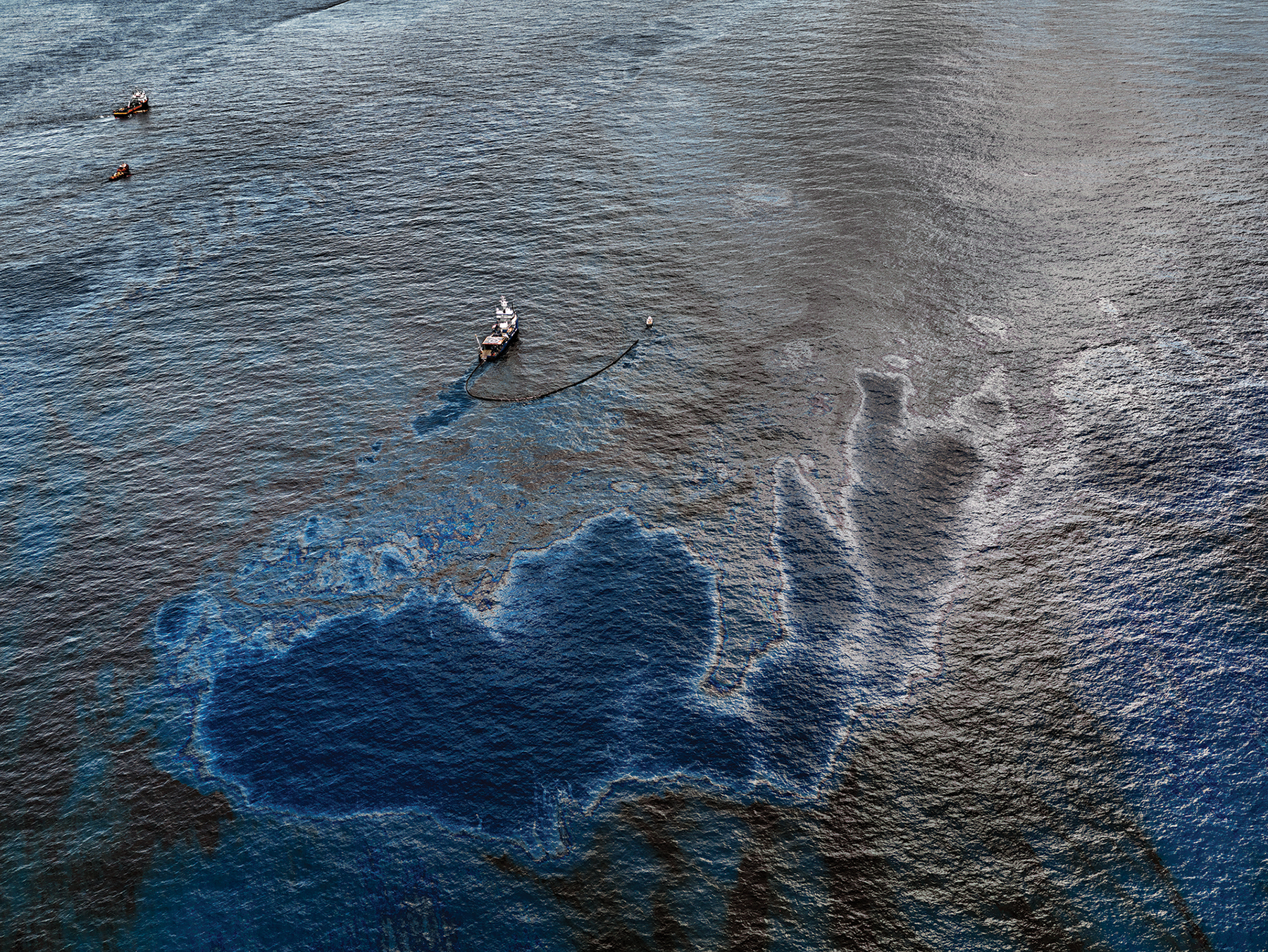

Oil Spill #4,

Oil Skimming Boat,

Near Ground Zero,

Gulf of Mexico,

June 24, 2010

Released in 2006, Manufactured Landscapes, a film about Burtynsky, directed by Baichwal, won a Genie for Best Documentary and Best Canadian Film at the Toronto International Film Festival. In 2013, the film Watermark, directed by Baichwal and Burtynsky, was awarded the Best Canadian Film award by the Toronto Film Critics and was later named Best Feature Length Documentary at the 2nd Canadian Screen Awards.

Burtynsky, Baichwal, and de Pencier’s third film, ANTHROPOCENE: The Human Epoch (2018) was part of a larger multidisciplinary project that included fine art photography, film, virtual reality, augmented reality, and scientific research. That endeavour points to humans as the primary cause of permanent planetary change. The proposed name for the current epoch puts human activity on par with the cosmic collisions of the past that wiped out many forms of life for eons.

Dam #6,

Three Gorges

Dam Project,

Yangtze River,

China, 2005

ANTHROPOCENE: The Human Epoch received a long list of awards and nominations, including the Ted Rogers Best Feature Length Documentary Award and Best Cinematography in a Feature Length Documentary at the 2019 Canadian Screen Awards.

Burtynsky’s own distinctions include the inaugural TED prize, which he shared with Bono and Robert Fischell, the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts — and he was awarded the title of Officer of the Order of Canada in 2008. He holds eight honorary doctorate degrees. Most recently, Burtynsky was recognized for his Outstanding Contribution to Photography by the World Photography Organization for the 2022 Sony World Photography Awards.

Clearcut # 1,

Palm Oil Plantation,

Borneo,

Malaysia, 2016

While Burtynksy has enjoyed great success exposing the environmental atrocities taking place around the world, there is a burden of knowledge that comes with his experiences. For the past 35 years, the wild places near his home in the Beaver Valley have provided some solace.

“For me to have access to this kind of place that we can call nature, that allows you to walk and free your mind — it’s a place to re-centre and it’s a place to really begin to think about what I have seen and what I still need to see. I often think that if I didn’t have this property I wouldn’t have that reference point to nature, because my work is always about the lament of the loss of places like this.”

Mines #22,

Kennecott Copper Mine,

Bingham Valley,

Utah, 1983

From his global vantage point, Burtynsky says he can see that the landscape around Southern Georgian Bay still possesses some balancing points between urban and rural areas, forests and agriculture, and private and public spaces. But he’s worried, and he warns us those fulcrums could easily be shifted by a ballooning population in the region.

“It’s a beautifully balanced area. Some might say that development has gone a bit far, but still I think it’s within reason — but as more people want to come here, I think it’s really important we preserve what makes this place special,” he says.

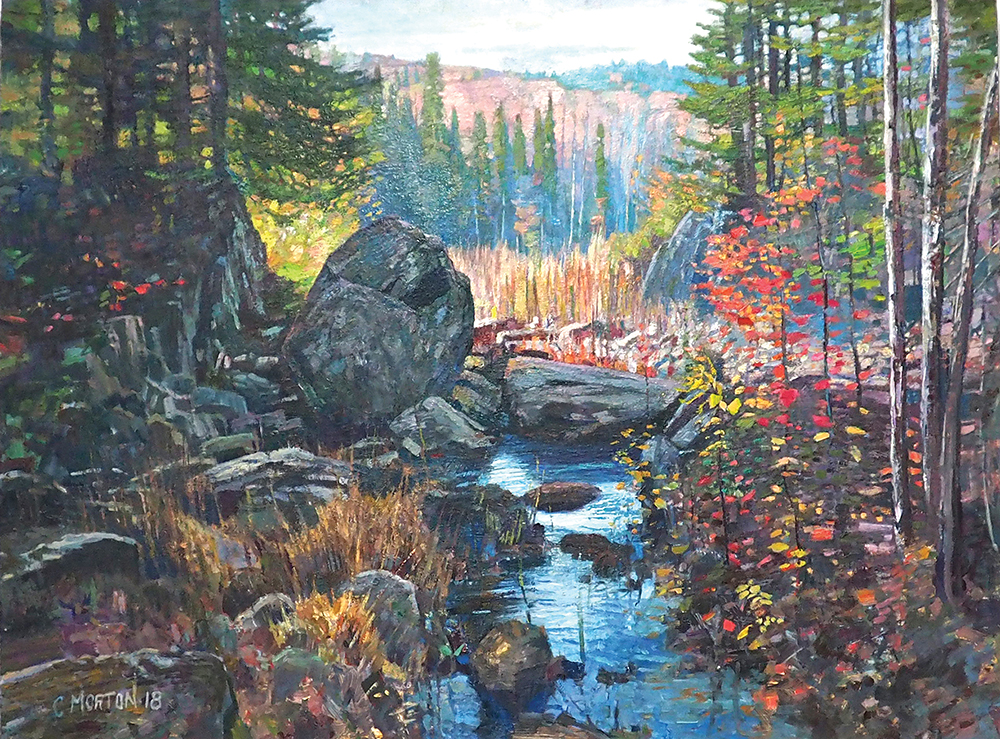

Natural Order #33,

Grey County,

Ontario, Canada,

Spring 2020

Edward Burtynsky talks

to On The Bay at his

home in the Beaver Valley.

Some of his most recent work includes a series of photographs entitled Natural Order. While in isolation during the early months of the pandemic in 2020, Burtynsky turned his camera onto the local landscape and focused on the dawning of spring in area wetlands. He says the wild and wet places are nature’s filters and the cornerstones of a sustainable future.

“That’s watersheds doing their work, that’s what nature does. It’s the great cleanser. We just have to let it do what it needs to do and not eat up the wetlands, not turn them into developments. We need to really fight for the balance that we need, to have a rich place that we can share with the wildlife that’s here, (so) the fish can thrive, and the animals can thrive in the forests, and the Bay can sustain a fishery and sustain fish. I think these are the things we want to be part of. We don’t want to dominate it. We want to be good custodians of this pretty special place.”