“A man is an animal first of all. And then he is a Social animal, Political animal and so on. I am an Art animal, that’s why, spectator, I need your physical and psychological efforts to make sense.” Oleg Kulik

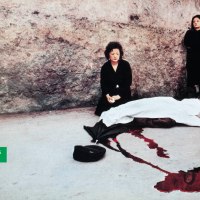

© Oleg Kulik, Mad Dog Performance (photographs), 1994

© Oleg Kulik, Mad Dog Performance (photographs), 1994

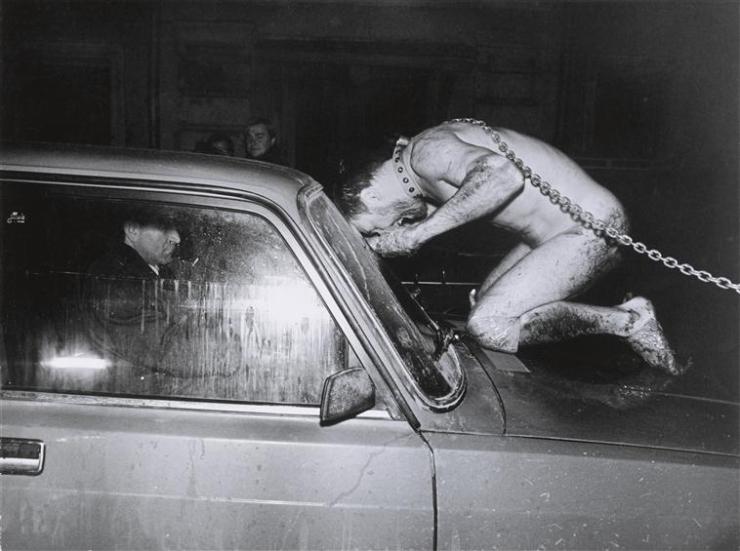

© Oleg Kulik, I bite America and America bites me, 1997

© Oleg Kulik, I bite America and America bites me, 1997

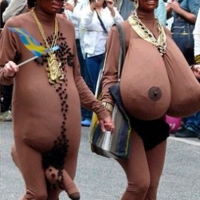

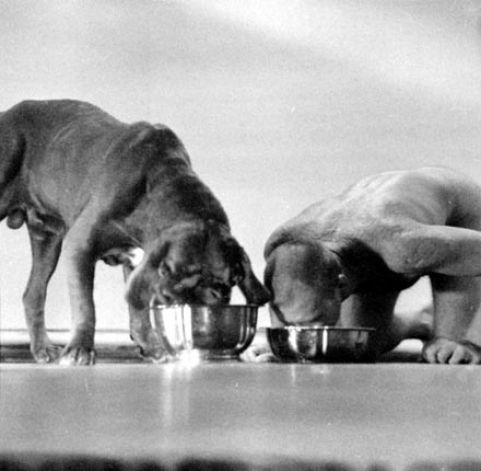

© Oleg Kulig, Family of The Future, 1997

© Oleg Kulig, Family of The Future, 1997

“Kulik has suggested: ‘I wanted to turn into a sort of new Diogenes, a dog-philosopher’ (2004:56); and, like Diogenes, the active force and vital optimism of his disruptive conduct is perhaps best understood as an uncompromising, transgressive hostility toward the inertia of conventional aesthetic and political gestures. In the uneasy transition to a post-Soviet Russia, the interventions of Kulik as a ‘clown of the catastrophe’ (Viktor Misiano in Watkins and Kermode 2001:63) engaged critically with dominant ideologies and alibis, and presented a range of political, philosophical, and ethical propositions through his bodily actions and accompanying statements. Some of the work explicitly denounced the corruption of the international art market and the commodificatory domestication of dissident aesthetics, as well as the Pavlovian conditioning of socialized gallery-goers. Other actions referenced specific political contexts, for example: the introduction of new capital punishment legislation in Russia during the 1990s, Russian elections (in which, like Beuys, Kulik put himself forward as the representative of the “Party of Animals”), the exclusions effected by the European Union, epidemics of animal disease, the fate of Montenegro in the breakup of former Yugoslavia, and so on. In particular, he returned repeatedly to relations between Eastern and Western Europe, and representations of contemporary Russia in the constitution of a new Europe as a deprived, unsophisticated, mongrel “other” that is charming as long as it remains passive, submissive, excluded, and doesn’t bite back. Kulik’s explicit critique of anthropocentrism seems to be a posthumanist extension of his radical misgivings about Eurocentrism, and a logical development of his critical stance on democracy’s blind spots and limitations. Kulik’s utterances contain echoes of a “deep ecology” in their utilitarian critique of the human subject. There are all sorts of other knowledges outside of the center, he proposes, if only one could create a new “united culture of noosphere” (in Watkins and Kermode 2001:14), an inclusive zoocentrist culture of the senses and of embodied perception”

“(…)

“What kind of dog was being represented here? The Kulik-dog, “a rag of wolf’s tongue redpanting from his jaws” (Joyce [1922] 1960:52), was ill-tempered, confrontational, combative; a wild, mad or fighting dog devoid of any of the other possibilities dogs actually possess. On some levels, it seems to have been little more than a rather reductive cartoonlike vicious dog, a “beware-of-the-dog” dog, territorial and irredeemably antagonistic, although arguably a great deal of courage must have been required to carry out this degree of pretence in many of the performance contexts Kulik chose. Becoming-dog here seems to have been a mimicry of selected attributes of canine behavior, an imitation game as spectacle directed at human beings (rather than, say, dogs). As Phillips has remarked in her critical appraisal of the Deleuzean trope of becoming animal: “Becoming is a fantasy that we do not really want to play out to its very end: to remain on the border-a human in a partial dog site, a dog with a human attitude-is about as far as we are willing to go” (2000:130). What remains remarkable, however, is the level of Kulik’s investment, the monstrous, amoral, libidinal, and exhibitionist energetics of his performance as “dog,” and the contextual, critical focus of his interventions.

Recently, Kulik has expressed certain reservations as to the effectiveness of his strategies in the Zoophrenia series (see for example Kulik 2004:56)-the reiteration of metaphor and stereotype in his representation of the animal as “non-anthropomorphous other,” as it is described by his collaborator Mila Bredikhina (in Watkins and Kermode 2001:52); the tendency for him as performer to collapse through immersive mimicry into a state of incoherent affectivity-and his recent work has moved away from Kulik-dog interventions of this kind. Nonetheless, in the unrestrained excess of his mimesis of aberrant canine behavior, Kulik managed to produce an indeterminate creature within which elements of the “animal” lurk alongside those of the “human,” rendering both terms and their constitutive difference unstable and in question: in Alan Read’s words, a “divided self of species relations” (2004:244).”

excerpt of Inappropriate/d Others or, The Difficulty of Being a Dog, by David Williams, in TDR (1988-), Vol. 51, No. 1 (Spring, 2007), pp. 92-118