Losing its id in the heart of the cosmos since 1949

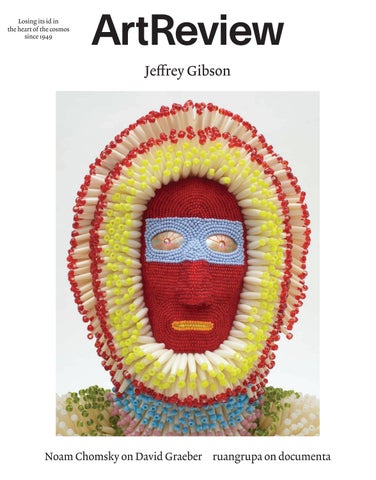

Jeffrey Gibson

Noam Chomsky on David Graeber ruangrupa on documenta

Mendes Wood DM São Paulo Kasper Bosmans, Creatures, 27/08 – 05/11 2022 Paula Siebra, Noites de Cetim, 27/08 – 05/11 2022

Mendes Wood DM Brussels Seulgi Lee, SLOW WATER, 08/09 – 08/10 2022 Miranda Feengyuan Zhang, Thus to sleep is sweeter than to wake, 08/09 – 08/10 2022 Nina Canell, 15/10 – 19/11 2022 Jean Claracq & Nathanaelle Herbelin, 15/10 – 19/11 2022

Mendes Wood DM New York Vojtěch Kovařík, Dusk of the Gods, 09/09 – 08/10 2022 Castiel Vitorino, 14/10 – 11/11 2022 Maria Auxiliadora 14/10 – 11/11 2022

Rua Barra Funda 216 01152 – 000 São Paulo SP Brazil 13 Rue des Sablons / Zavelstraat 1000 Brussels Belgium 47 Walker Street New York NY 10013 United States www.mendeswooddm.com info@mendeswooddm.com

Image: Kasper Bosmans, Mendes Wood DM São Paulo, 2022

Mend e s Wood DM

Robert Longo, Untitled (After Mitchell; Bleu, bleu, le ciel bleu, 1961), detail, 2022 Charcoal on mounted paper © Robert Longo / ARS New York, 2022

ROBERT LONGO The New Beyond Paris Marais October—December 2022

Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Dance at Molenbeek (year unknown) Design: NODE Berlin Oslo

PERES PROJECTS

MAK2

UGO RONDINONE

THE WATER IS A POEM UNWRITTEN BY THE AIR NO. THE EARTH IS A POEM UNWRITTEN BY THE FIRE

OCTOBER 18 - JANUARY 8

∣L∣A∣U∣R∣A§§§ ∣G∣R∣I∣S∣I§§§§§§ 0 ∣ 5 ∣ .∣ 1 ∣ 0 ∣ §§§§§§ 2 ∣ 9 ∣ .∣ 0 ∣ 1 ∣ .∣ 2 ∣ 3 ∣ § ∣M∣A∣M∣C∣O§ ∣G∣E∣N∣E∣V∣E§

Jenny Saville Latent 9 rue de Castiglione Paris

GAGOSIAN

ArtReview vol 74 no 7 October 2022

Queens In case you missed it, the (British) queen just died. In the past, ArtReview, which reported (in the name of art) on the coronation (and its potential effects on the uk artworld) and on the 1977 Jubilee, would probably have shut its offices for a week. The same week during which, in the uk, many of art’s (social) events were cancelled as a mark of respect. ArtReview didn’t do that. So, what’s changed? For a start, ArtReview has broadly republican views. The natural product of a concern with issues of fairness, opportunity and equality. (Although no critic ever judges everything equally, so they’re exempt; a special case.) But more importantly, in its attempts over the past few decades to report on, and, it rather modestly thinks, contribute to the pluralistic discourse that should be (but is not… yet) the bedrock on which any notion of a ‘global’ artworld is based, it’s no longer exclusively shaped by a uk point of view. Naturally it’s a bit sceptical about the very notion of a global artworld too – different contexts will lead to different outcomes, based on different ways of viewing the world, different access to resources and different ideas as to what constitutes art. Read, for example, in this issue,

Global Seoul

15

ruangrupa’s account of the process behind the development of documenta fifteen and Noam Chomsky’s examination of the late, great David Graeber’s legacy. But when it comes to conflicting ideas of the global and ArtReview’s relationship to them, hypocrisy is often the true bedrock on which the ‘global’ artworld is founded. And ArtReview has always reported on what it sees. Or something like that. That’s where differences of opinion (also a bedrock for art) come in. Perhaps what ArtReview is really trying to say is that when it comes to art and art history today, the winding path trumps the straight one. Being a critic is about opinions, of course. But it is also about the ability to change them, when change is justified. Which is why ArtReview is proud of the fact that its pages, over the years, have contained contrasting viewpoints, contradictory views and the occasional piece of plain bonkersness. (It tries to keep a lid on that obviously, but sometimes it’s important to go all the way, to dive right in, to push the pedal to the metal and see where you end up.) This issue though is bonkersness-free. Although you’ll have to be the judge of that. God save the king! (Only joking!) ArtReview

Global Seoul

ArtReview.Magazine

artreview_magazine

@ArtReview_

ARAsia

Sign up to our newsletter at artreview.com/subscribe and be the first to receive details of our upcoming events and the latest art news

16

The Realm of Matters No. 16, 2022 (detail), acrylic and porcelain pieces from kilns of the Song Dynasty with glaze writing on canvas, 150 × 110 × 16 cm © Hong Hao

Hong Hao

New Works

Hong Kong

pacegallery.com

Art Observed The Interview Giulia Cenci by Ross Simonini 28 Hello, Darkness by Mariacarla Molè 38

Shifting Sands by Martin Herbert 41 Call and Response by Cat Kron 42

page 42 Nancy Holt, Up and Under, 1987–98. © Holt/Smithson Foundation, licensed by Artists Rights Society (ars), New York

19

Art Featured

Jeffrey Gibson by Chris Fite-Wassilak 50

Ruangrupa Interview by J.J. Charlesworth & Mark Rappolt 74

Noam Chomsky on David Graeber Interview by Nika Dubrovsky 58

Sylvia Schedelbauer by Ren Scateni 82

Tyler Mitchell by Fi Churchman 66

The Future Will Be an Out of Body Experience by Venus Lau 88

page 82 Sylvia Schedelbauer, False Friends (still), 2007, digital video, 4 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist

20

261 Boulevard Raspail, 75014 Paris fondationcartier.com

Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori, Nyinyilki – Main Base, 2009. Private collection, Adelaide, Australia. © The Estate of Sally Gabori / Adagp, Paris, 2022. Photo © Simon Strong.

Great Australian Aboriginal painter

Art Reviewed

exhibitions & books 94 Aichi Triennale 2022, by Mark Rappolt The Dark Arts: Aleksandra Waliszewska and Symbolism from the East and North, by Phoebe Blatton Bill Lynch, by John Quin Mary Kelly, by Claudia Ross Black Melancholia, by Owen Duffy Carolee Schneemann, by Tom Denman Marcus Coates, by Adam Hines-Green Splendid Isolation, by Pádraic E. Moore Ghislaine Leung, by Maddie Hampton Out of the Margins: Performance in London’s Institutions 1990s – 2010s, by Bryony White Mark van Yetter, by Martin Herbert Desmanchar, Desfaz (Disrupt, Dissolve), by Oliver Basciano Sarah Sze, by Ben Eastham

How Not to Exclude Artist Mothers (and other parents), by Hettie Judah, reviewed by Adeline Chia Illuminations, by Alan Moore, reviewed by Chris Fite-Wassilak Folk Music A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs, by Greil Marcus, reviewed by Martin Herbert I Fear My Pain Interests You, by Stephanie LaCava, reviewed by David Terrien Best of Friends, by Kamila Shamsie, reviewed by Toby Lichtig Amy Sherald: The World We Make, reviewed by Nirmala Devi Death by Landscape, by Elvia Wilk, reviewed by Alice Bucknell Our Santiniketan, by Mahasweta Devi, reviewed by Mark Rappolt

page 94 Kate Cooper, Infection Drivers, 2018. Courtesy the artist (as seen at Aichi Triennale 2022)

22

from the archive 122

제여란 Je YeoRan

10.27– 1.19 Road To 2022 2023

스페이스K 서울 SPACE K Seoul

07802 서울시 강서구 마곡중앙8로 32

32, Magokjungang8-ro, Gangseo-gu, Seoul, 07802, Republic of Korea

02-3665-8918 www.spacek.co.kr spacek_korea

PIONEERS AND COLLECTIVES IN THE ARABIAN PENINSULA

SEP 6– DEC 11 2022

NYUAD-ARTGALLERY.ORG | +971 2 628 8000

NETI NETI LuYang NetiNeti 22.09.22

12.02.23

FREE ENTRY 176 Prince of Wales Road, London, NW5 3PT Check online for full programme zabludowiczcollection.com

Art Observed

everything 27

Photo: Luis Do Rosario. Courtesy the artist

28

ArtReview

The Interview by Ross Simonini

Giulia Cenci

“It’s about the freedom of imagining and it’s about everything which cannot be killed by contemporary society”

Giulia Cenci creates sculptural beings struggling into and out of life. Like feral beasts, they can be thin and sinewy. Like livestock, they can be plump, dismembered and displayed like taxidermy. More and more, Cenci places her creatures in silvery environments, in relationship to other pseudo-lifeforms, suspended in grids of cold metal. This work is clearly in conversation with other emerging sculptors and with climate activism, but Cenci is particularly mining ideas posed in the twentieth century, by Yves Tanguy, David Cronenberg, H.R. Giger and Lee Bontecou

– artists offered shockingly new speculations on technological life. Cenci’s imagination, she says, has been stimulated by science fiction, and her practice has been a parallel process of world-building. In her daily life, Cenci is fiercely independent, leaning towards the lifestyle of an off-the-grid doomsday prepper. She seems to have thrived in the pandemic, creating her most ambitious and widely seen installations yet, including dead dance (2021–22) at this year’s Venice Biennale, a 150-metre alley of hanging sculpture, inspired

October 2022

by agricultural equipment, and evoking the dread of an abattoir. Cenci is generally suspicious of urban culture, and she recently moved to the Italian countryside, where she is freeing herself of corporate food sources and industrial fabricators. On her farm, she has spent the last few years alternately living alone and opening her doors to a kind of intentional community. Along with these friends and coworkers, she is now at work on a summer camp, which will, among other things, teach people how to be sovereign.

29

A Kind of Anarchy ross simonini Where are you now? giulia cenci I’m in the south of Tuscany in the countryside, stealing internet from a friend because I have no internet at home. rs And you grew up in that region, right? gc Yeah. I left when I was 15, and I went to a small city, Perugia, to study art. Then I went to Bologna for the fine art academy, and came back here after 15 years away. rs Is your studio still in an old slaughterhouse? gc Yes. It was a farm. My father moved here from the area of Milano in the 60s. His parents were intellectuals – the father a journalist and art critic, the mother an illustrator – so they had nothing to do with farming. But he decided to buy this piece of land, which was extremely cheap, and start a farm with animals and a plantation. I moved back here because, when I had to produce the work for the maxxi Bulgari Prize in 2020, I needed space. There was this stable, which was used for pigs and is quite big and very nice, and which had been empty for 20 years or so. So I decided to turn it into my temporary studio. There is also endless space outdoors. I can try anything. So I started my own foundry,

where I melt aluminium. I use old car parts and everything is extremely cheap and easy to do, especially for me, because I like to do things by myself. The plan was to be here for a few months, but then I was kind of stuck because of many situations, including covid. rs Are you alone out there these days? gc The studio and the foundry are mine, but I had many people working with me. If anyone wants to melt, like, a piece of aluminium, they can just come here. Eventually this turned into a place where everybody lives together. We started to garden and eat together and have our own chickens. We wanted to be independent, especially in 2021. We can just use the food which is around us, and the same goes for the aluminium. We don’t buy pure aluminium, only leftovers. But after a while, the work became a little bit more insane in terms of production. So I moved away. I took a small house on the mountain, while the studio is in the valley. rs How did you go about building this community? gc The nice thing was that, because of the pandemic, the universities were all online. So the cities were all empty. And then through Instagram and other socials, I started to look for people who were based around here. And it became like a school, because if you didn’t know how to weld, we would teach you. You become

View of the artist’s studio, Pietraia, 2020. Photo: Luis Do Rosario. Courtesy the artist

30

ArtReview

quite independent in this sense, which I believe is nice. I personally really like to know how to do anything that is part of my process. And now we make everything at the place. We never ask third parties. rs Independence seems to be a crucial part of your life and work. gc Yeah, quite a lot. I mean, we live in a society which is trying to erase our own ability. We are overwhelmed by premade products, services and platforms which are telling us how to be, how to act, how our profile picture must be, or how incorrect our words or images can be. I believe that when you are isolated and able to do things yourself, you get a little bit of freedom, a kind of anarchy, which I think is quite necessary in these times.

Organised Nature rs The work has been expanding over the last few years. Your works lento-violento [2020] and the Venice piece are like sculptural communities, filled with many bodies and heads. Is this related to the communal way in which the work is being produced? gc Absolutely. Recently I started to realise that I grew up in a very rural environment, but rural in a sense where nature is manipulated by humans.

So it’s organised nature. I will never forget the first time I went to Milano by car and I saw buildings and I thought, ok, this is truly weird. And then I started to realise there is all this huge infrastructure around me, which is the city itself, with so many rules and constructions, which is gonna make my life somehow quite precise. And the cities are also full of this animal population, called pets, and all of a sudden, a piece of nature becomes another product. And then you got your dog, and this dog is just amazing because this is your own dog. But we’ve forgotten the wild side of our behaviour. And I started to wonder a lot about how to create kind of wild habitats, and how to make environments which are not so divided into animal, human and object. I wanted to build up, not just like an object, but an environment, because I felt so, uh, disconnected. We create a difference between a pet animal, which is precious and necessary, and an animal that can just be killed. And we do the same with humans. There are humans who are more important or powerful or even who have a different value. And all of that made me try to think about a new population where these kinds of hierarchies are not so strong. rs Do you dislike civilisation? gc I just hate the idea that everything can just be a product, an economical value. And if

it’s not sold, it’s trash. This makes me incredibly crazy somehow. rs There’s a human hierarchy imposed on the natural world that you seem to hint at in the work: plants are lower than animals, and minerals are less than life. But, of course, minerals are at the foundations of life – and your work. gc And what happens when you start bringing in things like plastic and things made by humans into that hierarchy? I really don’t understand the term ‘artificial’. I don’t get why the product of an animal is natural and the product of a human is unnatural. It’s really this attitude of bringing ourselves among all the rest. It’s imperialistic. Compared to us, minerals are inert. They appear still, but actually, if you look at them from an energetic point of view, something is moving inside, and this cannot be defined as stillness. And they also come from life. Plastic, too. What I always love to think about with plastic is that to make it we need oil, and oil is made by probably the oldest forest of this planet, which in thousands and thousands of billions of years became oil. So when I see a plastic bag moved by the wind, I have to think about a little piece of that forest. So I guess we need to rethink categories. This is also something which, to me, became quite clear from making sculpture. It’s always the same. We are all made of the same thing.

It’s incredible. And if we look at our home environment and ourselves from a very distant point of view, you see that this is even more evident. You can see it even by looking at the landscape. The plant doesn’t exist if there isn’t an insect. This is something that you learn at elementary school. Life is interdependent. rs Do you think about the longevity of your work in these terms? What will your objects become when nature swallows them back? gc I really like to think that at some point things will merge. But I also could never really work with bronze because for me it feels just too endless, you know? It’s so related to this idea of making a monument or making something which has to last forever. Time in the work is quite funny because we compare it to our own life. So if something is gonna last more than, like, 80 years, this is a long-term piece. But actually if you look at life on Earth, that’s nothing. Even plastic is turning into something else and is gonna be eaten and is already in our water system. So it’s all related to our own point of view, which for the planet is almost nothing. rs Right, a lot of the dialogues around climate change are about the ‘planet’ in an abstract sense, which I think confuses the idea for a lot of people. The real conversation is about humanity hurting itself.

View of the artist’s studio, Pietraia, 2020. Photo: Camilla Maria Santini. Courtesy the artist

October 2022

31

dead dance (guardians) (detail), 2021–22, metal, acrylic resin, fibreglass, quartz paint (installation view, The Milk of Dreams, 59th Venice Biennale, 2022). Photo: Andrea Rossetti. © the artist. Courtesy the artist, La Biennale di Venezia and SpazioA, Pistoia

32

dead dance (scalata), 2021–22, metal, acrylic resin, fibreglass, quartz paint (installation view, The Milk of Dreams, 59th Venice Biennale, 2022). Photo: Andrea Rossetti. © the artist. Courtesy the artist, La Biennale di Venezia and SpazioA, Pistoia

33

lento-violento (ininterrottamente) (detail), 2020, metal, acrylcast, found objects, studio dust, marble dust, volcanic ash, ash from the artist’s stove, bone black, dimensions variable. Photo: Giorgio Benni. © the artist. Courtesy the artist, maxxi, Rome, and SpazioA, Pistoia

34

gc Yeah, it’s like a suicide. I don’t think the planet is really gonna have a problem by turning into something else. Maybe we are gonna see the end of our own civilisation or the end of certain kinds of lives, but that doesn’t mean the planet is gonna die.

Pathetic and Beautiful rs Are you interested in using your work to evoke certain feelings about nature in people? gc I’m not sure that mine is a precise message. It’s not an answer to anything, nor a definition. For me, sometimes the feeling comes from behind your neck or in your belly. It’s about the freedom of imagining and about everything which cannot be killed by contemporary society. rs Is this the same kind of thing you’re looking for in other works of art? gc I like art that is capable of letting me travel and abandon my own life, to bring me to another habitat. If I think about my favourite movies – Tarkovsky’s Solaris or [Yorgos Lanthimos’s] The Lobster – those are all situations where I experience a new world in which rules are destroyed and new rules are made by the artists. rs Do you read much?

gc I love poetry. One of the most important books of my life has been The Waste Land, by T.S. Eliot. It’s a book which is able to get so much material from others and put it together to create a new narration, which leaves you so open, and so able to put yourself in it. It’s so experimental for me. I also love science fiction. During covid I enjoyed The Scarlet Plague, by Jack London, a pretty amazing short book. He’s talking about the end of culture from a fever, and actually what happens in the book is that the people who are gonna survive this fever are the ones away from the cities, who didn’t go to school or didn’t really have a cultural life. So they’re all super wild people, and they’re gonna grow this new society where they don’t even believe that something like a university should exist. But then there is this old man who survived who was a teacher at university, and he’s trying to tell people about painting and philosophy. He is both pathetic and beautiful, and for me there is a character like this in many of my works. rs Your work is often described as apocalyptic and dystopic. How do you actually conceptualise a word like ‘apocalypse’ at this point? gc I think it’s something that refers to another period of human history, but not now.

I mean, I remember when the Twin Towers collapsed and I was watching television and I could see it in front of my eyes. I was twelve years old. And I called my mom and she couldn’t believe it, because she was like, “You cannot watch this on television. It’s fake,” and I was like, no, Mama, I think that’s real. It’s like everything is so present. And even when things are very bad, we are watching it from a screen. And this isn’t the apocalypse, because you cannot get at it as an event. rs Is your art ever politicised as a tool in the climatechange conversation? gc To be an artist is already quite political to me, because I really had to decide on it. There were no artists around when I was growing up and it was not something common at all. But I would have to go to church a lot with my parents, and when I saw paintings in church, these were the most meaningful experiences I’d ever had. It’s such a beautiful thing to me. You decide to make something that no one else is making. You try to add something to the human view. For me, this is political. If one of my works could do what those paintings did for me, that would be something. Ross Simonini is a writer, artist, musician and dialogist. He is the host of ArtReview’s podcast Subject, Object, Verb

dead dance (maniatoia), 2021–22, metal, acrylic resin, fibreglass, quartz paint (installation view, The Milk of Dreams, 59th Venice Biennale, 2022). Photo: Andrea Rossetti. © the artist. Courtesy the artist, La Biennale di Venezia and SpazioA, Pistoia

October 2022

35

19—23 OCTOBER 2022 19—23 OCTOBER 2022 PREVIEW: 18 OCTOBER PREVIEW: 18 OCTOBER

After 8 Books, Paris Agustina San Juan AfterFerreyra, 8 Books, Paris Amanda Wilkinson, London Agustina Ferreyra, San Juan APALAZZOGALLERY, Brescia Amanda Wilkinson, London Artbeat, Tbilisi APALAZZOGALLERY, Brescia BQ, Berlin Artbeat, Tbilisi Bureau, New York BQ, Berlin Ciaccia Levi, Paris/Milan Bureau, New York Champ Lacombe, Biarritz Ciaccia Levi, Paris/Milan Chapter NY, New York Champ Lacombe, Biarritz Crèvecoeur, Paris Chapter NY, New York Croy Nielsen, Vienna Crèvecoeur, Paris Deborah Schamoni, Munich Croy Nielsen, Vienna Delgosha, Teheran Deborah Schamoni, Munich Derosia, New York Delgosha, Teheran Entrée, Bergen Derosia, New York Ermes Ermes, Rome Entrée, Bergen Fanta-MLN, Milan Ermes Ermes, Rome FELIX GAUDLITZ,Milan Vienna Fanta-MLN, Femtensesse, Oslo FELIX GAUDLITZ, Vienna Femtensesse, Oslo

35 BOULEVARD DES CAPUCINES, 75002 PARIS 35 BOULEVARD DES CAPUCINES, 75002 PARIS PARISINTERNATIONALE.COM PARISINTERNATIONALE.COM

First Floor Gallery, Harare Foxy New York First Production, Floor Gallery, Harare Georg Fine Arts, Foxy Kargl Production, NewVienna York Ginsberg Galeria, Georg Kargl Fine Arts,Lima Vienna Good Weather, Rock/Chicago GinsbergLittle Galeria, Lima greengrassi, Good Weather, Little London Rock/Chicago The Green Gallery,London Milwaukee greengrassi, Gregor Staiger, Zurich/Milan The Green Gallery, Milwaukee Grey Noise,Zurich/Milan Dubai Gregor Staiger, Hagiwara Projects, Tokyo Grey Noise, Dubai HigherHagiwara Pictures Projects, Generation, New York Tokyo Hot Wheels, Athens New York Higher Pictures Generation, Iragui, Moscow Hot Wheels, Athens Jacqueline Martins, São Paulo/Brussels Iragui, Moscow JacquelineKayokoyuki, Martins, SãoTokyo Paulo/Brussels Kendall Koppe, Tokyo Glasgow Kayokoyuki, KOW, Berlin Kendall Koppe, Glasgow Lars Friedrich, KOW, BerlinBerlin Lefebvre & Fils,Berlin Paris Lars Friedrich, Lodos, Mexico Lefebvre & Fils, City Paris Lodos, Mexico City

Lomex, New York Lucas Hirsch, Dusseldorf Lomex, New York LylesHirsch, & King,Dusseldorf New York Lucas Max Mayer, Dusseldorf Lyles & King, New York Misako & Rosen, Tokyo Max Mayer, Dusseldorf Galeri Nev,& Ankara/Istanbul Misako Rosen, Tokyo P420,Ankara/Istanbul Bologna Galeri Nev, Project Native P420,Informant, Bologna London Rhizome, Algiers London Project Native Informant, ROHRhizome, Projects, Jakarta Algiers Schiefe Zähne,Jakarta Berlin ROH Projects, Sophie Tappeiner, Vienna Schiefe Zähne, Berlin Sperling, Munich Sophie Tappeiner, Vienna Stereo, Warsaw Sperling, Munich Sweetwater, Berlin Stereo, Warsaw Temnikova & Kasela, Tallinn Sweetwater, Berlin Theta, YorkTallinn Temnikova & New Kasela, Three Star New Books, Paris Theta, York vonThree ammon co,Books, Washington Star Paris DC Pipeline, Detroit DC vonWhat ammon co, Washington What Pipeline, Detroit

We live in dark times. I write this in midsummer, while Italy faces the worst drought in 70 years and a less-rare government collapse, and think of how the art that I got to see in July (at a ‘utopian training camp’ in Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, and as part of the performance festivals at Centrale Fies, Dro, and in Santarcangelo) seemed to be responding to a prevailing mood that the end of the world is nigh – ecologically, economically, socially, pedagogically. Nevertheless, those performances invited audiences to take another look at the world as it is, with new eyes, before it vanishes. From this perspective, performance attempts to act as an exercise in affirmative action. So, welcome darkness. Time is up at the Fondazione, where Jonas Staal reclaims, via his utopian exhibition-cum-workshop Training for the Future. we demand a million more years, the means of production for a future that is already here. Over three days, the workshops or ‘trainings’ (which any visitor can sign up to) took place in a series of afternoon sessions led by practitioners from a range of disciplines. The trainers in question are tellingly called ‘world builders’. In a session featuring artist and educator Charl Landvreugd, the audience built a collective ‘world’ by placing, moving and replacing a series of objects – among them hairbands, watches and pens – donated by the

38

Hello, Darkness

Is there a place for performance art in this doomed world? Now more than ever, says Mariacarla Molè

Training For the Future. we demand a million more years, 2022, a project organised by Jonas Staal at Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

ArtReview

fellow participants. The trainers supervised this participatory process in which ideas are transformed into actions that reflect a desire to collectively write a possible and more inclusive future. By way of practices such as storytelling, rituals and tarot reading, the trainers tested out a community space that was cooperative and participative, safe and accessible. In this sense time was experienced as a trans-time: a time ruled by the ephemeral, the temporary and the elusive; a time that generates a form of knowledge unrelated to coherence, progression and linear narration, and one that works in illuminations and fragments, embracing a certain amount of randomness and chance. Similarly, the research centre for performative practices Centrale Fies (located in a former hydroelectric power station in Dro, Trentino) hosted the Live Works Summit, a three-day performance-oriented free school that tries to imagine a future mythology that embraces climate change, queer pain and multispecies parenthood. The result is exhilarating in Philippe Quesne’s postapocalyptic performance Farm Fatale (2019), in which five ecologist scarecrows discuss the effects of climate change, sing pop songs and hold up demonstration signs in a scene made up to look like a dystopian and abandoned farm. The future life imagined in Selin Davasse’s Multiplicity of Asia Minor (2022)

is feminine and foregrounds a multispecies society, one that demands a new mythology – a cosmogony with no founding father, but instead a nurturing surrogate mother. Sergi Casero, in El Pacto del Olvido (2022, and titled after the Spanish law approved after Franco’s death in 1975, which prevents legal investigation into crimes committed during the 40 years of dictatorship), insists on the importance of an oral and collective narration of history, especially when the official narratives are silent and criminally forgetful. Time is again embodied in Giulia Crispiani’s Mormorìo (2022), a love letter to bodies that multiply, breathe and pulse as one. Darkness also invades many of the performances in Santarcangelo. A postapocalyptic scenario appears again, in nomadic theatre company Motus’s performance Tutto brucia (2021), which draws on the myth of Cassandra (a prophet cursed by a jealous god so that no one would believe her premonitions) and mourns the end of a civilisation that’s trapped in its own nightmare, hypnotised by flames while everything around it burns. Sitting under a spotlight in a darkened space, Marina Otero tells her story Love Me (2022, cowritten with Martín Flores Cárdenas): she reveals her scars, and through her body evokes every pain (part of which relates to her departure from Buenos Aires to a new life in Spain) and the effects of time with heartbreaking strength. Meanwhile, Giovanfrancesco Giannini chooses violence in cloud_extended (2022). He forces his half-naked body to emulate poses from his digital archive of images and videos:

top Selin Davasse, Multiplicity of Asia Minor, 2022 (performance view, Centrale Fies, Dro, 2022). Photo: Alessandro Sala above Philippe Quesne, Farm Fatale, 2019 (performance view, Centrale Fies, Dro, 2022). Photo: Roberta Segata

October 2022

these range from the French-Italian singer Dalida, to different pictorial renditions of the goddess Venus, to tortured men accused of homosexuality in the Chechen Republic. A sense of togetherness and intimacy fill the dark space in which Alex Baczynski-Jenkins’s Untitled (Holding Horizon) (2018) is performed in fluid, long-lasting movements, something like a rave or a rite, but of the type you never wish to end. A picture emerges polyphonic, in terms of voices and practices, but quite uniform in premise, needs and hopes. Rituals return in a way that seems to be searching for a new language, but is nevertheless ready to leave behind narratives that can often seem trapped in the nihilist critique. And the same can be said of the rewriting of a mythology for our times. One constantly feels the not-very-reassuring sense of living in a time in need of major rehab. I saw broken people struggling to imagine a future, but working together in order to try. I saw bodies in need of radical softness, bodies that can provide it, bodies seeking to be together only as humans. I’m not sure if this time of darkness has made our eyes more sensitive, but I’m sure emerging from it will come with some pain. Mariacarla Molè is a writer based in Turin

39

CICEK GALLERY GALLERY CICEK

20 20 20 29 20 29 29 OCT 29 OCT OCT OCT POLITICS OF CHARM: POLITICS OF CHARM: POLITICS OF CHARM: WOMEN, BAME, QUEERS PROGRESS WOMEN, BAME, QUEERS &&PROGRESS WOMEN, BAME, QUEERS & PROGRESS POLITICS OF CHARM: WOMEN, BAME, QUEERS & PROGRESS

FreeEntry. Entry.1313Soho SohoSq, Sq,London, London,W1D W1D3QF 3QF Free Free Entry. 13 Soho Sq, London, W1D 3QF CuratedbybyVittoria VittoriaBeltrame Beltrame Curated byLondon, Vittoria W1D Beltrame Free Entry. 13Curated Soho Sq, 3QF Curated by Vittoria Beltrame AbiJoy JoySamuel Samuel Abi Abi Joy Samuel AllaSamarina Samarina Alla Alla Samarina Abi Joy Samuel Annam Butt Annam Butt Annam Butt Alla Samarina BerfinCicek Cicek Berfin Berfin Cicek Annam Butt FiaYang Yang Fia FiaCicek Yang Berfin KayGasei Gasei Kay Kay Gasei FiaHazell Yang Naila Naila Hazell Naila Kay Hazell Gasei Naila Hazell

It’s not always easy to identify the prevailing trends in contemporary art: since the coexistence of Pop and Minimalism during the 1960s and the subsequent advent of pluralism, art has tended to constitute a jostle of conflicting aesthetic and critical positions, the picture varying according to standpoint and taste. Of late, though, the landscape has seemed quite legible. If you’ve been visiting biennials or institutions and a fair swathe of forwardthinking commercial galleries, the art there is increasingly predicated on giving voice to the formerly underrepresented or trying to right former wrongs. Hence, to take a few recent examples, a Venice Biennale composed of 90 percent women artists, a Documenta full of collectives new to even seasoned Western art-watchers – along with evidence, via the media shitstorm, of the pitfalls of decentralised curating – and museum shows that, when they do spotlight dead white males (Hogarth at Tate Britain, for example, or German ‘colonial’ modernists at Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie), seek to preemptively point out said artists’ moral failings before the hanging jury of Twitter can do so. Also, and relatedly, living white male artists complaining, three beers in and off the record, that they’ll never get another show. And then there’s the art market, which, though it now leans more towards women artists and artists of colour than it used to, still seems primarily enraptured by eye-pleasing painting in dialogue with familiar historical aesthetics – witness the popularity of, for example, Anna Weyant, Christina Quarles, Flora Yukhnovich – which points in turn to an audience less interested in being challenged than in easy pleasure, handholding and maybe a quick profit. One can’t wholly blame said buyers, given the hurry of the auction houses to bundle art with any kind of luxury item in a kind of marvellous economic relativism, plus a phalanx of gallerists not too keen on wasting time educating new collectors towards knottier fare. Back in the museums and biennials, the much-needed shift in terms of who gets exhibited – and who decides who gets exhibited – is unthinkable without the righteous frustration and mobilising of social justice movements during the last decade or so, or the hair-trigger mood of social media. Given

Shifting Sands

Is contemporary art’s recent moral tide just a ‘moment’, asks Martin Herbert the spotlight, finally, underrecognised artists are naturally airing their grievances. Meanwhile, the ‘haves’ dependent on structural inequality in the first place are, as usual, shopping for baubles and using the biennials to network – the painterly Surrealism that was a signature of this year’s Venice Biennale is looking like a smart investment. Of course, this is a bit of a cartoon and there is art around, on show, that falls into neither of these camps – there are always exceptions, if you look – but the latter increasingly feels to fall outside of the larger, more pronounced dualistic paradigm. If you complain, though, especially from a position of longstanding privilege, that amid all of this you’re not seeing enough of the art you want to see (whatever that is), that moralistic gatekeepers are running scared or legislating for you, that you’re now aesthetically stateless, then you’re on sketchy ground. Jerry Saltz, on social media a few months back, opined that ‘in our time when art about “good causes” Jane Graverol, L’École de la Vanité, 1967, oil and collage on cardboard, 71 × 107 × 5 cm. © siae. Photo: Renaud Schrobiltgen. Courtesy Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt

October 2022

is automatically called “good”, it feels like the anxieties of the criticalacademic-curatorialmercantile class is [sic] imposing the definitions of these things on artists & limiting art to being “responsible” according to its rules’, and I’m still pondering what I think about that. I see enough examples of, say, complexity – a core virtue of art, for me – not being sacrificed in socially conscious art, though it can be harder to see when the work is being instrumentalised by curators, framed as a consumable message. It is, at the very least, something to wrestle with, perhaps while looking a little harder for the art that you want to see, giving time to art that you think you don’t and checking in often enough on the stuff that’s historically rung your cherries so that you remember why you got involved in the first place, which is healthy practice whatever else is going on. What’s certain, amid all this, is that contemporary art doesn’t stand still. The last time vanguard art practice felt this urgently politicised and was given a substantial stage on which to perform was the early 90s – recall, for example, the controversial Whitney Biennial of 1993 – and identity politics was the focus until, somehow, it wasn’t. Artists of my acquaintance who have been lofted in part by the recent rising moral tide are already wondering out loud if this is, again, just a ‘moment’, a trend, and if the artworld – and the clout-chasers within it, once clout is secured – will soon have lost interest, moved on to something else. Maybe: some commercial spaces, at least, have started to return to showing old white dudes, which felt almost unthinkable a year ago. Or possibly, given that increasing disparity and extremism (of wealth distribution, of public opinion) seems to be the trend, we’re set for a more pronounced version of the same: a contemporary art scene – or pair of scenes – set against a raging hellscape of contemporary reality, in which there’s no justification for either subtlety or nonprofitability, in which he, or she, who is not busy yelling is busy buying. In the meantime, the binary landscape offers one conspicuous virtue. In pointing combinedly to inequality, anger, blissful ignorance and gilded pleasure-seeking, and a residual degree of hope that conditions can yet be improved, it shows us precisely where we’re at right now.

41

Copenhagen in the summer is for swimmers. I’d mentally blocked the glowing accounts I’d read of Danish waters, assuming those extolling its virtues were of a hardier constitution. But the sea water that cleaves the city is temperate and astonishingly clean, and I needed it after attempting to walk across town to v1 Gallery in Copenhagen’s Meatpacking District. The Meatpacking District, a still semi-industrial expanse of warehouses near the waterfront, is one of the few stretches in this historic, green-bowered city that, on a hot day, rivals in blinding exposure the cement expanses of newer, more hastily built and less elegantly planned urban centres. Copenhagen’s galleries were mostly packing up summer group shows or shuttered in preparation for late August’s Art Week; I was grateful to find v1’s cool, naturally lit gallery open, and a solo show by the New-York-based painter Grace Metzler still up. Metzler’s faux-naïf paintings alternate between swathes of abstract pastels and distinctly articulated barrel-chested figures with limbs that snake and snarl around potato heads. These figures, who roam through domestic interiors

Call and response

A summer of art in Scandinavia leaves Cat Kron charmed and flushed

Grace Metzler, Doing what we can to help Dad feel like a kid again, 2022, oil and acrylic on canvas, 178 × 170 cm. Courtesy the artist and v1 Gallery, Copenhagen

42

ArtReview

and bucolic landscapes, are accompanied by narrative titles that manage to be both wry and tender. In Doing what we can to help Dad feel like a kid again (2022), an older male in shorts kicks his legs out as smaller figures extend a jump rope for him. Charmed and somewhat refreshed but still flushed from heat, I stumbled towards the harbour baths to be fully restored. An exemplar of Danish Modernist architecture and a mecca for modern and contemporary art for half a century, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art sits on Nivå Bay, facing Sweden, a half-hour north of Copenhagen. (You can swim here too, in the water visible just past the museum’s grounds.) I caught the tail end of the Dorothy Iannone exhibition, which maps the artist’s practice across six decades. The museum takes a variety of approaches to the challenge of the visual density of her work – mounting diaristic plates serially and reproducing spreads from sketchbooks as floor-to-ceiling wall dividers. The artist recounts periods of her life like erotic fairytales, chronicling her tumultuous relationships with lovers including artist Dieter Roth in An Icelandic Saga, a series of panels (from 1978, 1983 and 1986) whose magical-realist descriptions are undercut by frank admissions of Iannone’s own all-too-human struggles. An enlarged page from A Cookbook (1969) whose hand lettering could have been lifted from 1970s vegetarian dietary touchstone Moosewood Cookbook, features the following text, overlaid in all caps on a recipe that appears to be for creamed endive: ‘i had poisoned myself with tomato sauce infected with aluminum. i sadly sat on the toilet, expecting to die within 45 or 50 minutes, and studied my german.’ The text concludes, ‘i hope i live long enough to ____ what?’ In a 2016 interview with Maurizio Cattelan for Flash Art, the artist described her life and work as driven by a longing for ‘ecstatic unity’. And gathered here, her oeuvre registers as no less admirable for the periodic heartbreaks and other personal and professional setbacks of their author. On the far eastern edge of the Scandinavian Peninsula, the equally architecturally striking Bildmuseet was erected in 2012 on the Umeälven River, where it spills out into the Baltic Sea. Designed by the Danish firm Hanning Larsen, the spare, Siberian larch-panelled building is nestled into the university complex of Umeå, a college town in Sweden’s northernmost region and a hub of medical research, where the Nobel Prize-winning crispr gene-editing technology was developed. The institution’s mission statement is to showcase the intersection of art and science, a mandate in keeping with the generative principle behind the work of Nancy Holt, whose retrospective it organised over the course of the past several years while weathering the

global pandemic. Holt’s exploration into responsive design is encapsulated by her ‘Systems Works’, of which several ventilators from the series Ventilation System (1985–92) were on view. In her catalogue introduction, Lisa Le Feuvre, executive director of Holt/Smithson Foundation, writes, ‘Although largely assumed to be preoccupied with landscapes and the celestial realm, Holt was equally interested in manifestations and interpretations of architecture’, and the ventilators were envisioned as interior/exterior installations to highlight the bowels of tubing that course invisibly through the infrastructures of large buildings. They’re typical of Holt’s work, which in contrast to much of her Land-art peers is not only attuned to place as one finds it, but committed to working dynamically with its idiosyncrasies and specificities – extending in this case to the very air coursing through the building. This flexibility, exhibited during her lifetime, is evidenced by the works’ plans, which were designed such that the museum and foundation could in good faith present new iterations even eight years after her death. It was, however, no small task. In recreating the structures, the curators and Le Feuvre had to triangulate between archival blueprints and the specs of the museum to design a reiteration respectful of both the project and Bildmuseet’s sanctumlike architecture. My companion had booked a cabin on a pleasure cruise from Oslo to Copenhagen before our flight, and we needed to make it back to the west coast of the peninsula to meet our vessel. A Norwegian friend we explained this to was incredulous. Cruises in Scandinavia are, it turns out, regarded by locals much as they are everywhere else. (Personally, I say ignore the cynics.) Just as the region is a hub for artists spanning

the globe, it’s been heartening on trips made over the past five years to witness how artists within Scandinavia are supported and championed. We arrived the night before departure in time for the opening of Norwegian-born Gardar Eide Einarsson’s solo show at Standard (Oslo). The show bears the title Maybe It’s the Calm Before the Storm, Could Be the Calm, the Calm Before the Storm, quoting then-President Trump’s uncharacteristically lyrical comment made, seemingly apropos of nothing, to military leaders at a 2017 photo op. In one gallery, white-painted bricks are strewn across an otherwise bare floor. They’re arranged like tiny, rudimentary monuments, two bricks upright like bookends, with another resting on top, an arrangement used by prodemocracy protesters to slow the advancements of military vehicles during the 2019–20 demonstrations in Hong Kong. While the former us leader’s commentary seemed calculated for impact without a clear referent or intent, Einarsson’s referent was as explicit as his aim was unclear. What are we to make of these visual extrapolations of protest, however much we agree with the cause from which they have been taken? Ultimately however, that this exhibition felt unresolved was of less import than its maker’s conviction, and it was heartening to see work that challenges rather than answers given space. Cat Kron is a writer based in Los Angeles

top Dorothy Iannone, The Next Great Moment in History is Ours, 1970, serigraph on paper, 73 × 102 cm. © the artist. Courtesy Berlinische Galerie above Nancy Holt, Ventilation System, 1985–92 (installation view, Bildmuseet, Umeå, 2022). © Holt / Smithson Foundation. Photo: Mikael Lundgren. Courtesy Bildmuseet

October 2022

43

TICKETS ONLINE ONLY

55. INTERNATIONALER KUNSTMARKT 16. — 20. NOVEMBER 2022

200x131_ART22_H_ArtReview_Stoerer_INT.indd 1

08.09.22 13:50

Tu e s d a y 4 O c t o b e r | 1 0 a m Stansted Viewing | 2 & 3 October pictures@sworder.co.uk | sworder.co.uk

Damien Hirst, ‘6441 No Shelter’ from The Currency series, £10,000-£15,000

December 1–3, 2022 Photograph taken by Mateo Garcia / Belle & Company

Art Featured

or imagined 49

Jeffrey Gibson by Chris Fite-Wassilak

50

In joyful, speculative work, the artist unpicks and repatterns mythologies around the depiction of native cultures

51

above They Play Endlessly, 2021, canvas, acrylic paint, vintage beaded wallet, vintage wooden broach, archival pigment print on rice paper, beads, artificial sinew, sequins, nylon thread, 169 × 128 × 8 cm preceding pages The Body Electric, 2022 (installation view, Site Santa Fe). Photo: Shayla Blatchford

52

ArtReview

A gridded metal frame on the wall pops with a colourful series of cultures: the solemn-faced men in ceremonial costumes, the halfembedded canvases and woven bead patterns. Some of the canvases naked naïfs immersed in nature – stereotypes of noble dignity and in They Play Endlessly (2021) bear dizzying geometric designs in bright strength in suffering that arose to paper over the erasure and eradicapurples and pinks, on top of which are set small faces made of beads; tion of native people. Such images still abound in American culture: several feature simplified depictions of Native Americans, one with a the kneeling maiden of the Land-O-Lakes butter logo; the Chicago profile of a man wearing a feathered headdress, another seemingly a Blackhawks ice hockey team; Saturday morning reruns of Disney’s children’s book illustration of a young boy with long hair, held back cartoon Little Hiawatha (1937) – continual reinforcements of native by a red headband, looking over a grass field. Next to these in the culture as something exotic, other, past. They Play Endlessly also holds grid, a few canvases spell out statements in chunky, stylised letters: some quieter material histories, with many of its patterns made up of ‘The myth persists’; ‘You’re gonna miss me when I’m gone’. a mixture of plastic, glass and crystal beads, as nods to the beadwork Myth, play and refusing to disappear: the kaleidoscopic swirl that existed in native cultures before the arrival of Europeans during of They Play Endlessly serves as a concise introduction to the work of the fifteenth century; the size and shape of traded glass beads, made American artist Jeffrey Gibson, encapin Venice and Bohemia, eventually led Dolled up in intricate beadwork sulating as it does his use of painting, to changes in the forms and styles of the craft and collage as means to unpick beadwork being made. And gliding over and bright kitsch plumes, and repattern what is understood as such stories are the endless patterns Gibson’s flamboyant artefacts mock and bold statements that feature across contemporary Native American culture. the anthropological impulse, Gibson’s canvases, murals, sculptures The designation ‘American’ is of course a reductive simplification, a convention while buzzingly suggesting new rituals and costumes; phrases deployed in previous bodies of work had drawn that belies its long trail; Gibson’s ancestors are of the Cherokee and Chocktaw tribes indigenous to the more from dance and club hits of the 1980s and 90s – from Mr Finger’s continent that only relatively recently came to be denominated as deep house track Can You Feel It (1986), to Whitney Houston’s It’s Not ‘North America’, though Gibson himself was raised, and has lived Right but It’s Okay (1998). Now they increasingly look to poetry and and worked, internationally, coming to be based in Hudson Valley, political proclamations, like ‘To feel myself beloved on the earth’, a New York. Nor is his work rooted in a fixed geographical location, line from Raymond Carver’s 1988 poem ‘Late Fragment’, or the phrase and as such it raises questions not so much of belonging but of affini- attributed to Frantz Fanon, via Malcolm X, ‘by any means necessary’: ties and proximities. As with They Play Endlessly, it often has an imme- statements that stop us and ask how we might rewrite the present. diate, vibrant punch, whose playfulness belies the knotted layers of Firebelly (2021) is a beaded sculpture of a simplified bird, its red history that shape it, with each work asking how we might continu- and gold wings flecked with turquoise, its eyes translucent heart shapes. Such sculptures, of various animals and uncertainly humanally reshape an understanding of what indigeneity is. The pseudo-quilt of They Play Endlessly, installed as part of The Body shaped figures that populate Gibson’s exhibitions, draw in part on his research and work reconfiguring the collecElectric (2022), Gibson’s recent solo exhibition at Site Santa Fe, displays some of the persistent tions of institutions such as the Newbury Library The Body Electric, 2022 (installation view, mythology embedded in depictions of native and the Field Museum of Natural History in Site Santa Fe). Photo: Shayla Blatchford

October 2022

53

i am a rainbow, 2022, found punching bag, glass beads, artificial sinew, acrylic felt, 127 × 36 × 36 cm. Photo: Max Yawney

54

ArtReview

Untitled Figure 1, 2022, fringe, glass beads, artificial sinew, tin cones, sea glass, acrylic felt, steel armature, powder coat varnish, 180 × 79 × 61 cm. Photo: Shayla Blatchford

October 2022

55

Because Once You Enter My House It Becomes Our House, 2020, plywood, posters, steel, leds and performances, 1,341 × 1,341 × 640 cm. Photos: Brian Barlow (top); Emily Johnson (above)

56

ArtReview

Chicago, and the Brooklyn Museum, seeing what objects are held in their respective collections as representations of ‘native culture’. Some of these are simply offhand tchotchkes, sold at roadsides and tourist sites; such items aren’t high-end craft but are still framed as tokens of a culture. It could just be someone making what they thought was a nice design, but by virtue of the exchange it becomes a souvenir of the idea of authenticity. As Gibson has put it, he was drawn to how this type of object ‘wasn’t native enough and it wasn’t not native enough’. This statement provides a useful lens through which to consider his work as a whole – as a set of ambiguous props, emblems of a tangled, patchwork culture still in formation, yet to take flight. Dolled up in intricate beadwork and bright kitsch plumes, Gibson’s flamboyant artefacts mock the anthropological impulse, while buzzingly suggesting new rituals: ‘proposals’, Gibson has suggested, ‘for future hybridity’. Alongside such figures, hanging from the ceilings are often elaborate costumes and beaded punching bags from Gibson’s long-running series, usually bearing statements of character, intent and energy. On the punching-bag work All I Ever Wanted, All I Ever Needed (2019), the euphoric romanticism of the Depeche Mode lyric (from the 1990 track Enjoy the Silence) takes on a tinge of weary self-acceptance when it is cast in baby-blue beading on a punching bag made up with brown and yellow chevrons with a rainbow skirt, dangling expectantly above the gallery floor. The actions that have been continuously implied in Gibson’s installations – of boxing and weaving, sure, but most often of clubbing, dancing and other rituals of ecstatic movement – have more recently been realised, with works that act literally as backdrops and stages for meetings, discussions and performances. i am your relative, held earlier this year in the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto, was an area of moveable seating, the furniture and walls all covered in posters of eye-popping patterns: a space to configure relations and relationships. Stickers that people could place as they saw fit were given out, bearing statements such as ‘Their Dark Skin Brings Light’; ‘They Choose Their Family’; ‘Respect Indigenous Land’. This last phrase was also blazoned across the pastel ziggurat Because Once You

Enter My House, It Becomes Our House (2020), a temporary sculpture that sat outside in Socrates Sculpture Park in New York for eight months, hosting events by native collaborators such as choreographer Emily Johnson and composer Raven Chacon. In the performances there, and at others such as Gibson’s exhibition in Santa Fe, performers wore long, colourful robes cut from the same cloth, as it were, as Gibson’s posters and murals, bearing yet more slogans: ‘She Knows Other Worlds’; ‘They Teach Love’; ‘Speaking to the Sky’; ‘She Rewrites History’. These are determined, unashamedly optimistic statements, casting their wearers as participants in an uncertain ritual, enacting a spell that might move beyond scarred histories and reshape what is to come. In their essay ‘Who Belongs to the Land?’ (2022), indigenous American writer Lou Cornum proposes an Indigenous Futurism that is ‘about the struggle for a different future as well as a distinctly different idea of “future” – one that goes beyond the conflict between tradition and progress, and asks us to inhabit the present’. While Gibson’s neon clubbing-nostalgia and nods to native ceremonial wear draw from the past, it is towards such an inhabitation of an unmoored present that Gibson gestures. In the video A Warm Darkness (2022), created from a performance held around the Our House sculpture, performer Mx. Oops dons a hot-pink hoodie and matching bowl-shaped wig, dancing angularly, happily alone within the scaffolding inside the sculpture. It’s joyful, spurious, obscured. The performance and video cast Our House as a tomb, a place to put things to rest; as well as a haven, a shelter, in which to dance just for yourself; and a site from which our rewriting of the present might take place, a place where, as Cornum puts is, ‘there is no pre-apocalypse or post-apocalypse, only perpetual revelation’. ar the spirits are laughing, a survey exhibition of Gibson’s work, will open at the Aspen Art Museum on 4 November; They Come From Fire, a new site-specific installation at the Portland Art Museum, Oregon, will be on view from 15 October to 26 February; a selection of new works by Gibson will also be presented at Stephen Friedman’s booth at Frieze London, 12–16 October

A Warm Darkness (still), 2022, hd video, 29 min 19 sec all images © and courtesy the artist

October 2022

57

Manufacturing Enlightenment Noam Chomsky discusses true democracy, ‘bewildered herds’ and the fragility of the present in response to Pirate Enlightenment, the final book by late anthropologist David Graeber Interview by Nika Dubrovsky

Noam Chomsky at the Center for Art and Media (zkm) in Karlsruhe, 2014. Photo: Uli Deck / dpa picture alliance / Alamy Stock Photo

58

As questions of decolonisation rub up against the legacy of Enlightenment thinking in the West, anthropologist David Graeber argues in his posthumous book Pirate Enlightenment, or the Real Libertalia (to be published early next year) that Enlightenment ideas themselves are not intrinsically European and were indeed shaped by non-European sources. The work focuses on the proto-democratic ways of pirate societies and particularly the zana-malata, an ethnic group formed of descendants of pirates who settled on Madagascar at the beginning of the eighteenth century, and whom Graeber encountered while conducting ethnographic research at the beginning of his academic career. Graeber, author of Bullshit Jobs: A Theory (2018), Debt: The First 5000 Years (2011) and The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (written with the archaeologist David Wengrow), died in 2020, but in a wide-ranging conversation for ArtReview, his widow, the artist and author Nika Dubrovsky, speaks with Noam Chomsky, an admirer of the anthropologist’s work, about Graeber’s last project, neoliberalism and democracy, Western empiricism and imperialism, free speech, Roe v. Wade in the us, the war in Ukraine and how Germany’s Documenta art exhibition has barely coped with inviting non-Western artists to direct it for the first time. One of the left’s foremost thinkers, Chomsky has written major works that include Syntactic Structures (1957), Manufacturing Consent (1988) and, most recently, The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic and Urgent Need for Radical Change (2021, with C. J. Polychroniou). nika dubrovsky Thank you very much for the interview. It’s a great honour. We wanted to discuss David’s last posthumous book, Pirate Enlightenment, which will be published in January 2023 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. In this book, as in his other writings, David talked about the importance of dialogue. He describes how entire cultural traditions emerge from the creation of new stories and how these traditions are then remade and edited. noam chomsky That was very interesting. Both in his essay ‘There Never Was a West’, but also in the book about the extensive contributions of Native American thinkers [The Dawn of Everything, 2021, with David Wengrow], Chinese thinkers and others who, as they point out, as David points out, were recognised as contributors at the time, but then wiped from the tradition. It was regarded as just a literary technique or something. But

I think he makes it very clear that it was a substantive contribution. The discussion in ‘There Never Was a West’, about the nature of influence, was quite enlightening. The different ways in which influence takes place, in which it’s interpreted, and––as the tradition is constructed later – is filtered out, as he points out, on the basis of arguments that, if they were applied generally, would wipe out almost everything, including the tradition itself. One of the most interesting parts of The Dawn of Everything, I thought, were the sections on the interactions with the Native American philosopher and thinker, and his contributions to how Enlightenment thought was developed by leading figures. nd Just before Thomas Hobbes wrote Leviathan, he had seen a play by Charles Johnson, The Successful Pyrate, performed on an English stage. David suggested that this experience with Madagascar pirates may have

form. But when you go back to the original interactions, as David did and as they do in The Dawn of Everything, you see that what was filtered to become the accepted tradition is a sharp reconstruction of what actually happened – eliminating many interactions and many kinds of drawing on different voices, different experiences into something that was then reshaped by elite opinions. Particularly striking, I think, was his discussion, in ‘There Never Was a West’, of periods when state authority was inoperative for one reason or another, either not paying attention or weakened. It’s at that time that interactions at the ground level developed the basic meaningful contributions to whatever functions later as democracy. That’s where they arose, that’s how they can develop. But not the top-down conceptions that are reconstructed as our traditional heritage. It has lots of implications for direct action in the present. I think his emphasis is on things like the Zapatistas in the past, on relatives, work on pirates and so on. Pirate democracy in Madagascar and others is quite striking in that respect. nd In the Malagasy society that David lived in for several years and knew very well, dialogue is used as a political tool to shape public space. In your book Manufacturing Consent [1988, with Edward S. Herman], you describe how public space and the public imagination in Western countries is controlled from the top down by powerful ideological institutions.

influenced Hobbes’s political thinking. The very idea that people could negotiate with each other; that power could be organised not only top-down but also horizontally, as it was in many pirate communities, and in some indigenous cultures, came as a surprise to Europeans. David often said that his task was to decolonise the Enlightenment; to change our ideas of what kind of society we would like to live in. If we rethink our ideas about the Enlightenment, about where it came from, how do you think this will change the public imagination? nc I think we must pursue more carefully these insights into how that tradition, as he points out, becomes the reconstruction of the past by elite thinkers who reshape it into a particular David Graeber. Courtesy Goldsmiths, London

nc Ed Herman, who passed away recently, was the prime author of that. He was a specialist in finance and taught at the Wharton School. He was interested in the institutional structure of the media and how basic institutional factors lead to the shaping of the information system that’s created. We slightly differed on that, I should say. My own feeling is that while all of that is important, I don’t think it’s very different from the general intellectual culture. My own work has mostly been, actually, on elite intellectual culture, which doesn’t have those same institutional pressures, but nevertheless leads to a version of reality that’s not very different from what comes out of the media system. The phrase ‘manufacturing consent’, of course, is not ours. That comes from [American political commentator] Walter Lippmann. Also Edward Bernays, the main founder of the public relations industry. The two of them were members of Woodrow Wilson’s Committee on Public Information, the first major state propaganda agency, the so-called Creel Committee, which was designed to try to turn a pacifist population into raving anti-German fanatics

59

from top A Betsimisaraka henhouse and rice barn, 1911, Fenerive, Madagascar, photo: Walter Kaudern; Betsimisaraka women in Madagascar, c. 1900. Both images in the public domain. A subset of the Betsimisaraka, termed the zana-malata, were a focus of David Graeber’s dissertation research, from which Pirate Enlightenment is derived

60

ArtReview

as the Wilson administration moved into the war. Both Lippmann and Bernays were very impressed by the success in creating a fabricated version of atrocities and so on, which in fact did change opinion dramatically. Lippmann called this technique ‘manufacturing consent’, which he called a new art in the practice of democracy. He thought that’s exactly the way things should work. As David points out in his text, elite opinion has always been radically antidemocratic all the way through. Democracy is just regarded as ‘mob rule’, as Lippmann put it; the responsible men have to protect themselves from the roar and trampling of the bewildered herd. Lippmann, incidentally, was the leading liberal public intellectual in the twentieth century, a Wilson, Roosevelt, Kennedy liberal. But he was reflecting the general liberal conception of how the public has to be put in its place as spectators, while the serious guys – us – do the work of running society in the public interest. This is almost universal. It’s not just in the media. People like Reinhold Niebuhr [an American theologian] and Harold Lasswell, one of the pioneers of modern political science. Bernays went on to be one of the founders of the public relations industry, which devotes hundreds of billions of dollars a year to these efforts to control opinion and attitudes. But it’s all based on the same conception that the public is a bewildered herd, stupid and too ignorant for their own good. You have to control them in one way or another, not permit democratic tendencies. Perhaps you know the major scholarly work, the gold standard for scholarship on the Constitutional Convention, called The Framers’ Coup [2016, by Michael Klarman], the coup by the framers against democracy. They feared democracy, and they devised all kinds of techniques to prevent it effectively. If you look back at the Constitutional Convention, the only participant who objected to this was Benjamin Franklin. He went along, but he didn’t like it. Yes, it is correct that this shows up in the media, but it seems to me to show up in the media not only because of the institutional structures that Herman’s work mostly outlined but also because of deeper currents in cultural history. It’s the same thing in the English Revolution in the seventeenth century when you didn’t have these structures, ‘The Men of the Best Quality’, as they called themselves, must subdue the rebel multitude. When you read the history of the English Revolution, it looks as if it was a conflict between king and parliament, but that overlooks the public who were producing very extensive pamphlet literature and people travelling

around giving talks and so on. They didn’t want to be ruled by a king or parliament. The way they put it was, “We want to be governed by people who know the people’s sores, people like us, not by knights and gentlemen who do just want to oppress us”. That’s the English Revolution, the major current that was of course suppressed mostly by violence. The same thing shows up in the American Revolution a century later. David points out it’s a deep part of the Enlightenment. One of the striking points that he makes in the essay is that these concepts of human rights, Enlightenment, justice and so on, appeared in what’s called the West only at the time when they came into confrontation with other societies and cultures. In the whole long period before that, nobody ever bothered with such things. That can’t just be an accident. And I think we see it right through history, in a way, back to Aristotle’s Politics.

“Pointing out the many options that there are for developing more enlightened, more free societies, not just the ones encoded in our artificial traditions, which exclude lots of what happened and reshape the rest into fitting into convenient frames for existing power systems. I think that’s a tremendous contribution”

One of the arguments against allowing women to vote in the constitutional debates was it’s unfair to unmarried men because a married man would have two votes: himself and his property. This runs right through American history. It isn’t until 1975 that the Supreme Court officially determined that women are people, peers, who can serve on federal juries. So Alito’s opinion is quite right. In all of American history and tradition, there’s nothing to suggest that women have rights. Therefore, Roe is breaking from the tradition by saying, ‘Yes, women should have rights’. It’s not exactly the message he wanted to convey, but it’s the essence in which his opinion is historically accurate. It’s basically since the 1960s that there has been real pressure for not only women’s rights, but even freedom of speech. You look back at history, there’s no history of protection of freedom of speech. You begin to get the elements of it in the twentieth century, mostly in dissents. But it was not until the 60s that there was strong public popular pressure, sufficient for the Supreme Court to take a fairly strong position. Actually, in the current regression, major figures in the Supreme Court, Clarence Thomas, are saying they want to rethink those decisions that establish freedom of speech, like Times v. Sullivan. We may go back to the tradition, just as we’re doing with the revision of Roe. These are very tenuous achievements. We have to struggle for them every minute.

nd I found it very interesting how David links gender politics and the social status of women. Western societies in general are patriarchal, but the communities in Madagascar described by David in his book are not, so it is odd that it is us who are considered to be democratic.

nd The Paris salons, where many of these Enlightenment ideas were formed, mostly in endless conversations, were run largely by women. David’s Pirate Enlightenment talks a lot about war. He describes how the opposing sides put coloured signs on their foreheads, blue and yellow, to be able to distinguish one another in battle. War is also a dialogue, but a masculine one, where the instruments of communication are reduced exclusively to violence. For the characters in David’s book, however, the war ends in Assemblies, which restore complex human conversations. If we think about our current situation, what is most striking is the insistence on the abandonment of all dialogue and any exchange of opinions.

nc Actually, that has very interesting, very current implications. The Roe v. Wade case, if you read [Supreme Court Justice Samuel] Alito’s actual opinion, his decision, is quite interesting. What he says is that there’s nothing in history and tradition that supports the idea that women have rights, which is quite true. If you look back at the constitution, the framers – for them women weren’t even persons. They were property. That’s Blackstone [Commentaries on the Laws of England, 1765–69, by William Blackstone], English common law. Women are property owned by the father and handed over to the husband.

nc Yeah. That’s again a very timely issue. As you know, the nato Summit [in Madrid at the end of June] received lots of attention, very positive attention. One crucial element of it, which hasn’t received much discussion, bears exactly on what you’re talking about. If you look at the nato strategic statement, I think it’s Article 41, the basic thrust is we cannot have discussions and negotiations about Ukraine. It must be settled by violence. Those aren’t the words that are used, but that’s the meaning of the words. What they say is that the question of admission of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia and Ukraine into nato is not up for discussion.

October 2022

61

No third party can have any voice in it. We will decide as we wish. That’s a way of saying, ‘There cannot be any negotiations’. It’s been understood for 30 years, long before Putin, that no Russian leader will ever accept having Georgia and Ukraine in a hostile military alliance. That would be lunacy from Russia’s strategic point of view. Just look at a topographic map or the history of Operation Barbarossa [Nazi Germany’s 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union] and you can see why. That’s been understood by high us diplomats and directors of the cia. All of them have warned against this. But nato, meaning the us, just decided that doesn’t matter. We’re going to continue to insist that everything be settled by violence, not by negotiations. No dialogue. It’s probably the most important part of the nato Summit, and it’s consistent with what us policy has been. No discussion, just force.

makes the rules, and everybody else obeys or else. That’s the rules-based international order. And you can demonstrate that that’s the way it works, but you can’t penetrate elite discussion with this. I can talk about my own experience, but it’s just anybody in the same system can talk about it. My apartment in Cambridge was a couple of blocks away from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. I wasn’t allowed to cross the threshold unless they couldn’t prevent it. Like, if I was invited by an international organisation or the foreign press or a student group, then they had to allow it. But otherwise it was considered contaminating the premises by even talking about these topics.

nd You are a prominent scholar who has worked in Western academia for many years. I know nothing about academia except that David thought it was conservative and almost reactionary, and wrote extensively about it. Perhaps the very idea that it is possible to substitute dialogue with others for direct violence while preserving democracy and freedom within our own space is shaped and supported by the Western academic community.

nd Sometimes it feels like we’re seriously close to the end of the world. David, however, was an eternal optimist. No matter what was going on, he would say, “Okay, let’s look on the bright side. What can we do? How can we find a way out of it?” He tried very seriously to help [former uk Labour leader Jeremy] Corbyn, but when Corbyn got crushed, David almost fell into a depression for a while. Very soon, however, he focused on the Brain Trust Project, a group of academic and nonacademic activists and artists trying to create an independent thinktank to address climate change. Yet our current situation, the disasters we are facing on such a scale, it is difficult to keep being optimistic.

nc My academic life has been for 70 years at the elite institutions: Cambridge, Mass; Harvard, mit, others like them, Oxford and so on. All the same. Ideas of this kind can scarcely penetrate. They are immune to consideration of the fact that the system that they were embedded in is based on violence and suppression. The theories that are developed, like international relations theory, completely miss much of this. The security of the population is almost never a consideration in formation of government policy. Security of elite interest, yes. Not security of the population. In fact, this shows up very dramatically if you look at contemporary documents. Take the nato Summit again. The phrase ‘rules-based international order’ occurs repeatedly, over and over again. We have to preserve ‘the rules-based international order’. The phrase ‘un-based international order’ never appears, not once. There is a un-based international order, like the un charter, but the us doesn’t accept it. It bars all the activities that the us carries out. The big struggle with China, ideologically, is that China is insisting on the un-based international order. The United States wants a rulesbased order. The hidden assumption is the us makes the rules. We want an international order, which is basically the mafia. The godfather

nc Whatever our personal sentiments are about the likelihood of disaster, we have to maintain the ‘optimism of the will’. There are opportunities, whatever they are, and we have to devote ourselves to them. Take Corbyn. Very significant. I mean, if Corbyn had become prime minister, as it seemed in 2017 that he might very well do, it could be a very different England. Instead of being just a vassal of the United States, which it is, it could have been an independent element in world affairs. He could have joined with Europe to lead an independent Europe, which could have made accommodations with Russia prior to the invasion, when it was a possibility. Instead of just falling into the lap of the United States and becoming a total dependency, which is what happened. The British establishment knew what it was doing. The establishment all the way over to The Guardian, the so-called left. It’s very dangerous to allow a person to gain power who’s trying to create a popular-based political party that will reflect the interests of its constituents instead of concentrated private power. He was succeeding in that, and that’s much too dangerous to allow. So the whole establishment, from what’s called the left over to the right, just launched an incredible campaign to discredit him, very

62

ArtReview

successfully. Totally fraudulent grounds, but a very interesting illustration of the manufacture of consent, which is much broader than just the institutional structures involved. It’s based on a real understanding that popular power is just too dangerous to permit. It will threaten elite dominance in all domains and could lead to not only an independent popular-based democracy in England but even to independent moves in world affairs, which would undermine the mafialike structure. Quite a lot is at stake in keeping somebody like Corbyn out. nd David vividly describes how the democratic structures of pirate communities were influenced by Madagascar’s traditions. The pirates chose a captain who had full authority over the crew during combat, but not in everyday life. Many of these pirate traditions are strikingly similar to anarchist practices and are truly democratic, allowing each member of the community to shape the social environment around them, unlike our current ‘democracy’, which is built on institutions that prevent people from access to decisions about how they might live. nc As he stressed greatly, you don’t have democracy if representation is of the kind that liberal theorists call for. So take the main liberal theorists of democracy, people like Walter Lippmann, for example, or Harold Lasswell, or others. In this picture, the public has a role. Their role is to show up periodically and cast their weight in favour of one or another member of the elite class that represents power, and then go home and let them run the world but don’t do anything more. That’s what’s called democracy. And as David stressed, that has no resemblance to democracy. Democracy means direct participation in decision-making at every level. You can delegate responsibility to someone temporarily to carry out or play some administrative or another role. For example, in the Native American tribes that he discussed, where you pick a war leader for a particular conflict and then listen to him during the conflict, then he goes back and joins everyone else. That’s like the pirates, in fact, electing a captain because they need somebody to make decisions and then take them back. But it’s the public itself that always has the power and can, if it wants, take over decision-making. If you don’t have a structure like that, it’s not democracy. And of course, such structures can be developed. Let’s go back to Corbyn. If he had succeeded in creating the kind of Labour Party he was working for, it would have been a constituent-based party with local groups putting their input into direct decision-making

David Graeber hosts a debate at the London School of Economics during the campus-wide programme Resist: Festival of Ideas and Actions, 2016. Photo: Peter Marshall / Alamy Live News

October 2022

63