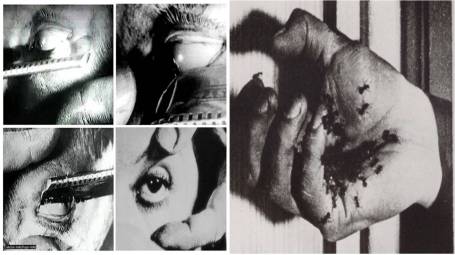

Salvador Dalí and Luis Bunuel’s scandalous endeavor Un Chien Andalou (1929) is capable of eliciting a collective wince even after 90 years of its creation. In the opening sequence when a male hand slices a female eyeball and the fluid flows out, its much obvious to ‘feel’ the need to flinch your eye or tighten your fist when you see a male hand with crawling ants. Why does that happen? Why can’t we just ‘look’ at it like any other cinematic image? Are occcularcentrism and Psychoanalysis just enough to explain the tactile qualities and corporeal experience of cinema?

Redefining the relationship between cinema and the spectator, Vivian Sobchak asserts that film theory has been reluctant to recognize the phenomenological aspects of film viewing as a bodily experience. Since “at the movies our vision and hearing are informed and given meaning by our other modes of sensory access to the world” (Sobchack,2004,p60), it is easier to make sense of the experience of watching an unusual surrealist imagery of Un Chien Andalou. The recurrent motifs of wounded, severed and sexual advancements through hands create a fidgety sensation and make the viewer feel disgusted as the disjointed images flow one after the other.

The opening sequence is particularly important to understand that how the sensation of a film is experienced by the skin through eyes. The first shot of male hands sharpening the razor and then the close-up of a cigarette smoking man put your senses in suspicion that something horrible is going to happen. Then, when the famous eye-slicing scene follows, one’s body reacts by looking away or expressing disgust. “That is, we do not experience any movie only through our eyes. We see and comprehend and feel films with our entire bodily being”. (Sobchack,2004,p63).

By Swati Bakshi

References

Elsaesser, T. and Hagener, M. (2015). Film theory: An introduction through the senses. New York: Routledge.

Sobchack, V. C, (2004).Carnal thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkley: University Of California Press.