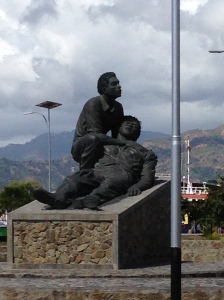

Monument to Sebastiao Gomes, killed in 1991, Dili, Timor-Leste (2015 photo)

This sentence has been written a thousand times: On 12 November 1991, Indonesian soldiers opened fire on unarmed protesters at the Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili, East Timor, killing more than 250 people and injuring many more. The massacre was neither the first nor the last in the period of Indonesian military occupation, which lasted from 1975 to 1999, but one thing was different: it was the first time international journalists were present as witnesses, the first time a massacre in East Timor was captured on film, the first time that foreign citizens were among those killed and beaten. The film footage screened around the world, leading to a wave of outrage and activism. The fuller story has been told many times – Clinton Fernandes’ Companion to East Timor being one of the most accessible.

25 years later, East Timor is independent as the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste (first declared days before the Indonesian invasion in 1975). In the final days of Indonesian rule, some outside governments started to support Timorese self-determination (Canada did so in 1998, for instance).

At the time of the Santa Cruz massacre, however, those governments did not. Documentary evidence continues to emerge and much is still hidden. But what there is shows that Western governments knew very well what had happened; that it was a cold-blooded act of revenge (in the words of one US State department official days later, speaking to a Canadian counterpart) by Indonesian soldiers; and that many more were killed than the Indonesian government would admit. Some outside governments raised concerns with the Indonesian government, but none shifted to support the Timorese right to self-determination. In the days following the Santa Cruz massacre, only one G7 country – Canada – suspended any aid. Denmark and the Netherlands were the only other Western countries to link aid to human rights. No country linked trade or went further than raising concerns on human rights grounds.

As documents continue to emerge, I share here two new documents from the days immediately after the Santa Cruz massacre, from Canadian government archives. The first is an initial report on what happened that day, from the Canadian embassy in Jakarta. The story was much worse than had been thought, the embassy reported. The army’s story was false, people in Timor were “terrified,” and it seemed that army officers had decided deliberately to shoot protesters in cold blood. The document indicates that Western governments knew, almost immediately, that the massacre was deliberate and that the Indonesian army was being dishonest.

Canadian embassy report on Santa Cruz massacre, dated 14 Nov. 1991: cej-massacre-report-1991-11-14

Despite this knowledge, few Western governments planned anything more than verbal protest to the Indonesian government. A second report from the Canadian embassy one week after the massacre indicates that no Western embassy in Jakarta had received any instructions to take any concrete action, other than words of concern. After a meeting of 12 Western and ASEAN embassy political counsellors, “general impression was business as usual.” Only Canada had decided to review its aid to Indonesia. Only 4 of the 12 countries (Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States) had made official protests over the massacre. No country had altered plans for official visits to Indonesia or East Timor, including military visits.

Canadian embassy report on meeting of embassy political counsellors, Jakarta, dated 20 Nov. 1991: cej-embassies-meeting-report-1991-10-20

International support for Timorese self-determination began to increase after the Santa Cruz massacre, but the inclination of most governments in the days that immediately followed the massacre was, in the words of the Canadian embassy in Jakarta, to carry on with “business as usual.” It is only as Timorese resistance continued and public protest in the Western countries mounted that any Western government started to look at taking action any stronger than words.