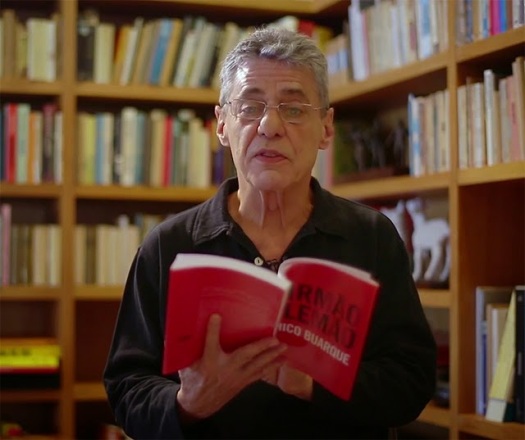

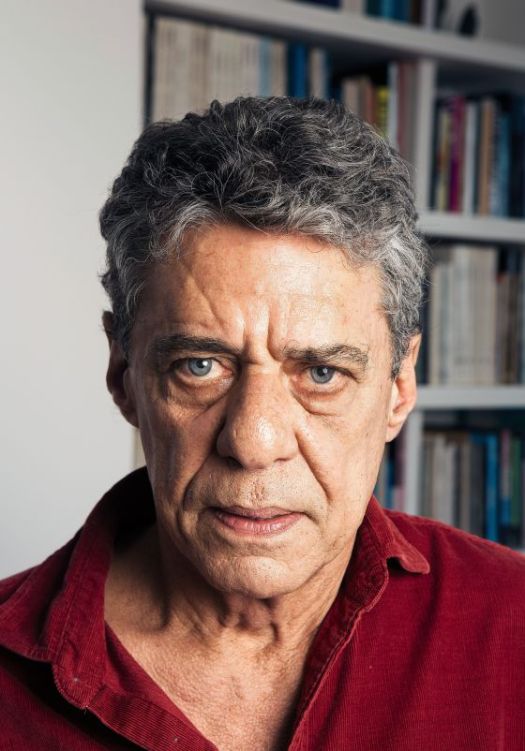

Before I began My German Brother, Chico Buarque’s fifth novel, I didn’t know a lot about the author. I was vaguely aware that he was a beloved Brazilian singer/songwriter and novelist who often writes on themes of love and politics, and who is now a handsome elder statesman in his seventies. In short, a sort of Brazilian Leonard Cohen.

The novel turns out to be another example of “autofiction” (a genre I’m reading a lot of lately, more by accident than design) and a coming of age story. The narrator and the author share the same full name – Francisco Buarque de Hollanda – but the narrator’s diminutive is slightly different, “Ciccio” instead of “Chico.”

They share other biographical facts as well, as I later learned, including a father who was a famous Brazilian historian and “man of letters” who fathered an illegitimate son in Germany when he was a newspaper correspondent in Berlin in 1930.

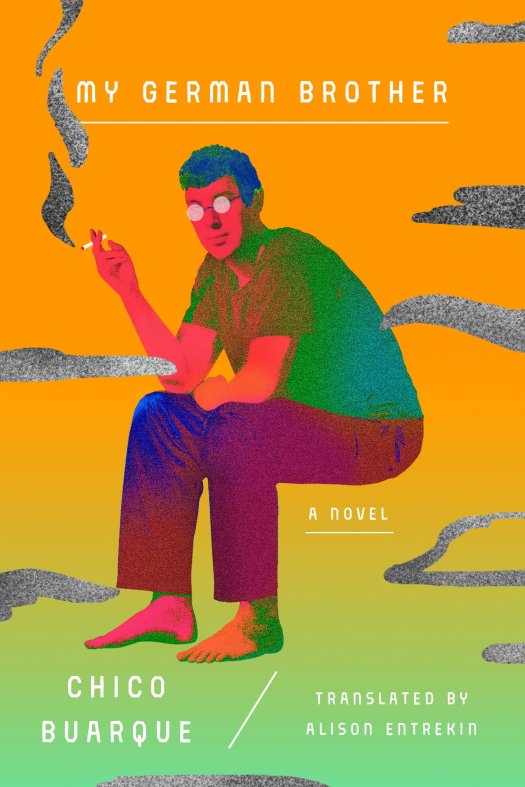

But, the novel is fiction and Ciccio Buarque isn’t entirely Chico Buarque. The book was a huge bestseller in Brazil when it was first published in 2014 and much of its popularity must have come from Brazillian readers already being familiar with parts of Chico Buarque’s life story and that of his father. The novel has just been published in English, in a colloquial and bawdy translation by Alison Entrekin. It is a great romp, and I don’t think that being unaware of how much Ciccio’s story departs from Chico’s own is that much of a hindrance to enjoying the book’s sense of adventure and personal curiosity.

The novel opens with 16-year-old Ciccio living in his father Sérgio’s book-stuffed house. Sérgio has over twenty thousand books. “It was the largest private library in São Paulo after that of a rival bibliophile who, according to Father, hadn’t read a third of what he owned.” Ciccio is trying to become a bibliophile like his father, but Sergio pays him no attention, doting only on Mimmo, the oldest son who only reads comics and looks at the pictures in Playboy magazine.

Ciccio seems to hope that his love of literature will eventually endear him to his father but is still intimidated by his indifference. “One day I might reveal to Father that I sort of managed to read half of War and Peace in French, and that now, with the help of an English dictionary , I was labouring through The Golden Bough,” he says.

Stuck between the pages of The Golden Bough Ciccio finds an old letter sent from Berlin to his father in 1931, written “in German and teeming with capital letters.” Ciccio can’t quite translate the letter but thinks he grasps its main subject.

“I know that as a single man my father lived in Berlin between 1929 and 1930, and it isn’t hard to imagine him having an affair with a local Fräulein” he thinks. “In fact, I seem to remember talk of something more serious. I think a while back someone said something about a child he’d fathered in Germany. It wasn’t an argument between parents, which a child never forgets; rather, it was like a whisper behind a wall, a quick exchange of words that, by rights, I couldn’t have heard, or couldn’t have heard right. And I forgot about it…”

Bourque’s choice of Frazer’s The Golden Bough as the vessel for this revelation is perfect, as that Victorian history of magic and religion teems with fertility rites and sacrificially murdered kings.

Ciccio finally finds someone to translate the letter and becomes obsessed with the knowledge that he has an illegitimate older brother living an unknown life on the other side of the world.

He begins to fantasize about his brother, whom he learns was named Sérgio after his father, and begins to imagine his life. Did he become a Hitler Youth or was there some hint of Jewish blood in the family? Did he and his mother move to Brazil and try and get in touch with his father or where they forever embittered toward him?

Ciccio continues to brood about his brother as he passes through adolescent rebellion, stealing cars with his pal Thelonious, and sexual adventures with his brother Mimmo’s cast-off girlfriends. The novel unfolds in dreamlike sequences that keep the reader wondering what is real and what is the product of Ciccio’s overstimulated imagination.

After the protests of 1968 and the beginning of the Brazilian military dictatorship in 1969 both Ciccio’s friend Thelonious and his brother Mimmo are among the many young men who were “disappeared” — arrested and murdered without a trace by the regime. Ciccio becomes even more obsessed by his unknown German brother and even begins to conflate him with the missing Brazilian brother.

The novel ends with a coda where Ciccio, now a retired teacher in his seventies finally goes to Germany and learns the fate of his unknown brother, which is further expanded on in a short author’s note.

Chico Buarque’s brother was given up for adoption and raised as Horst Günther. He found out about his actual parentage at the age of 22 and changed his name to Sérgio Günther. He was a well known singer and television host in East Germany, providing pro-Communist comedic propaganda. He was also a womanizer, like the fictitious Mimmo, having married three times and is rumoured to have fathered an illegitimate child in Yugoslavia. He died in 1981, from lung cancer at the age of fifty.

My German Brother is a clever and a lovingly imaginative fever dream of a novel in which Buarque looks at questions of identity, destiny and our relationships to authority, whether it is the Nazi or Communist regimes in Germany, the military dictatorship in Brazil or even one’s own icily distant and dismissive father.

My German Brother by Chico Buarque (translated from the Portuguese by Alison Entrekin) Farrar, Straus and Giroux 208pp.