This is part 24 of Categories for Programmers. Previously: Comonads. See the Table of Contents.

We’ve seen several formulations of a monoid: as a set, as a single-object category, as an object in a monoidal category. How much more juice can we squeeze out of this simple concept?

Let’s try. Take this definition of a monoid as a set m with a pair of functions:

μ :: m × m -> m η :: 1 -> m

Here, 1 is the terminal object in Set — the singleton set. The first function defines multiplication (it takes a pair of elements and returns their product), the second selects the unit element from m. Not every choice of two functions with these signatures results in a monoid. For that we need to impose additional conditions: associativity and unit laws. But let’s forget about that for a moment and just consider “potential monoids.” A pair of functions is an element of a cartesian product of two sets of functions. We know that these sets may be represented as exponential objects:

μ ∈ m m×m η ∈ m1

The cartesian product of these two sets is:

m m×m × m1

Using some high-school algebra (which works in every cartesian closed category), we can rewrite it as:

m m×m + 1

The plus sign stands for the coproduct in Set. We have just replaced a pair of functions with a single function — an element of the set:

m × m + 1 -> m

Any element of this set of functions is a potential monoid.

The beauty of this formulation is that it leads to interesting generalizations. For instance, how would we describe a group using this language? A group is a monoid with one additional function that assigns the inverse to every element. The latter is a function of the type m->m. As an example, integers form a group with addition as a binary operation, zero as the unit, and negation as the inverse. To define a group we would start with a triple of functions:

m × m -> m m -> m 1 -> m

As before, we can combine all these triples into one set of functions:

m × m + m + 1 -> m

We started with one binary operator (addition), one unary operator (negation), and one nullary operator (identity — here zero). We combined them into one function. All functions with this signature define potential groups.

We can go on like this. For instance, to define a ring, we would add one more binary operator and one nullary operator, and so on. Each time we end up with a function type whose left-hand side is a sum of powers (possibly including the zeroth power — the terminal object), and the right-hand side being the set itself.

Now we can go crazy with generalizations. First of all, we can replace sets with objects and functions with morphisms. We can define n-ary operators as morphisms from n-ary products. It means that we need a category that supports finite products. For nullary operators we require the existence of the terminal object. So we need a cartesian category. In order to combine these operators we need exponentials, so that’s a cartesian closed category. Finally, we need coproducts to complete our algebraic shenanigans.

Alternatively, we can just forget about the way we derived our formulas and concentrate on the final product. The sum of products on the left hand side of our morphism defines an endofunctor. What if we pick an arbitrary endofunctor F instead? In that case we don’t have to impose any constraints on our category. What we obtain is called an F-algebra.

An F-algebra is a triple consisting of an endofunctor F, an object a, and a morphism

F a -> a

The object is often called the carrier, an underlying object or, in the context of programming, the carrier type. The morphism is often called the evaluation function or the structure map. Think of the functor F as forming expressions and the morphism as evaluating them.

Here’s the Haskell definition of an F-algebra:

type Algebra f a = f a -> a

It identifies the algebra with its evaluation function.

In the monoid example, the functor in question is:

data MonF a = MEmpty | MAppend a a

This is Haskell for 1 + a × a (remember algebraic data structures).

A ring would be defined using the following functor:

data RingF a = RZero

| ROne

| RAdd a a

| RMul a a

| RNeg a

which is Haskell for 1 + 1 + a × a + a × a + a.

An example of a ring is the set of integers. We can choose Integer as the carrier type and define the evaluation function as:

evalZ :: Algebra RingF Integer evalZ RZero = 0 evalZ ROne = 1 evalZ (RAdd m n) = m + n evalZ (RMul m n) = m * n evalZ (RNeg n) = -n

There are more F-algebras based on the same functor RingF. For instance, polynomials form a ring and so do square matrices.

As you can see, the role of the functor is to generate expressions that can be evaluated using the evaluator of the algebra. So far we’ve only seen very simple expressions. We are often interested in more elaborate expressions that can be defined using recursion.

Recursion

One way to generate arbitrary expression trees is to replace the variable a inside the functor definition with recursion. For instance, an arbitrary expression in a ring is generated by this tree-like data structure:

data Expr = RZero

| ROne

| RAdd Expr Expr

| RMul Expr Expr

| RNeg Expr

We can replace the original ring evaluator with its recursive version:

evalZ :: Expr -> Integer evalZ RZero = 0 evalZ ROne = 1 evalZ (RAdd e1 e2) = evalZ e1 + evalZ e2 evalZ (RMul e1 e2) = evalZ e1 * evalZ e2 evalZ (RNeg e) = -(evalZ e)

This is still not very practical, since we are forced to represent all integers as sums of ones, but it will do in a pinch.

But how can we describe expression trees using the language of F-algebras? We have to somehow formalize the process of replacing the free type variable in the definition of our functor, recursively, with the result of the replacement. Imagine doing this in steps. First, define a depth-one tree as:

type RingF1 a = RingF (RingF a)

We are filling the holes in the definition of RingF with depth-zero trees generated by RingF a. Depth-2 trees are similarly obtained as:

type RingF2 a = RingF (RingF (RingF a))

which we can also write as:

type RingF2 a = RingF (RingF1 a)

Continuing this process, we can write a symbolic equation:

type RingFn+1 a = RingF (RingFn a)

Conceptually, after repeating this process infinitely many times, we end up with our Expr. Notice that Expr does not depend on a. The starting point of our journey doesn’t matter, we always end up in the same place. This is not always true for an arbitrary endofunctor in an arbitrary category, but in the category Set things are nice.

Of course, this is a hand-waving argument, and I’ll make it more rigorous later.

Applying an endofunctor infinitely many times produces a fixed point, an object defined as:

Fix f = f (Fix f)

The intuition behind this definition is that, since we applied f infinitely many times to get Fix f, applying it one more time doesn’t change anything. In Haskell, the definition of a fixed point is:

newtype Fix f = Fix (f (Fix f))

Arguably, this would be more readable if the constructor’s name were different than the name of the type being defined, as in:

newtype Fix f = In (f (Fix f))

but I’ll stick with the accepted notation. The constructor Fix (or In, if you prefer) can be seen as a function:

Fix :: f (Fix f) -> Fix f

There is also a function that peels off one level of functor application:

unFix :: Fix f -> f (Fix f) unFix (Fix x) = x

The two functions are the inverse of each other. We’ll use these functions later.

Category of F-Algebras

Here’s the oldest trick in the book: Whenever you come up with a way of constructing some new objects, see if they form a category. Not surprisingly, algebras over a given endofunctor F form a category. Objects in that category are algebras — pairs consisting of a carrier object a and a morphism F a -> a, both from the original category C.

To complete the picture, we have to define morphisms in the category of F-algebras. A morphism must map one algebra (a, f) to another algebra (b, g). We’ll define it as a morphism m that maps the carriers — it goes from a to b in the original category. Not any morphism will do: we want it to be compatible with the two evaluators. (We call such a structure-preserving morphism a homomorphism.) Here’s how you define a homomorphism of F-algebras. First, notice that we can lift m to the mapping:

F m :: F a -> F b

we can then follow it with g to get to b. Equivalently, we can use f to go from F a to a and then follow it with m. We want the two paths to be equal:

g ∘ F m = m ∘ f

It’s easy to convince yourself that this is indeed a category (hint: identity morphisms from C work just fine, and a composition of homomorphisms is a homomorphism).

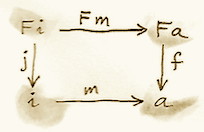

An initial object in the category of F-algebras, if it exists, is called the initial algebra. Let’s call the carrier of this initial algebra i and its evaluator j :: F i -> i. It turns out that j, the evaluator of the initial algebra, is an isomorphism. This result is known as Lambek’s theorem. The proof relies on the definition of the initial object, which requires that there be a unique homomorphism m from it to any other F-algebra. Since m is a homomorphism, the following diagram must commute:

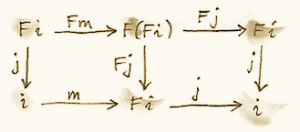

Now let’s construct an algebra whose carrier is F i. The evaluator of such an algebra must be a morphism from F (F i) to F i. We can easily construct such an evaluator simply by lifting j:

F j :: F (F i) -> F i

Because (i, j) is the initial algebra, there must be a unique homomorphism m from it to (F i, F j). The following diagram must commute:

But we also have this trivially commuting diagram (both paths are the same!):

which can be interpreted as showing that j is a homomorphism of algebras, mapping (F i, F j) to (i, j). We can glue these two diagrams together to get:

This diagram may, in turn, be interpreted as showing that j ∘ m is a homomorphism of algebras. Only in this case the two algebras are the same. Moreover, because (i, j) is initial, there can only be one homomorphism from it to itself, and that’s the identity morphism idi — which we know is a homomorphism of algebras. Therefore j ∘ m = idi. Using this fact and the commuting property of the left diagram we can prove that m ∘ j = idFi. This shows that m is the inverse of j and therefore j is an isomorphism between F i and i:

F i ≅ i

But that is just saying that i is a fixed point of F. That’s the formal proof behind the original hand-waving argument.

Back to Haskell: We recognize i as our Fix f, j as our constructor Fix, and its inverse as unFix. The isomorphism in Lambek’s theorem tells us that, in order to get the initial algebra, we take the functor f and replace its argument a with Fix f. We also see why the fixed point does not depend on a.

Natural Numbers

Natural numbers can also be defined as an F-algebra. The starting point is the pair of morphisms:

zero :: 1 -> N succ :: N -> N

The first one picks the zero, and the second one maps all numbers to their successors. As before, we can combine the two into one:

1 + N -> N

The left hand side defines a functor which, in Haskell, can be written like this:

data NatF a = ZeroF | SuccF a

The fixed point of this functor (the initial algebra that it generates) can be encoded in Haskell as:

data Nat = Zero | Succ Nat

A natural number is either zero or a successor of another number. This is known as the Peano representation for natural numbers.

Catamorphisms

Let’s rewrite the initiality condition using Haskell notation. We call the initial algebra Fix f. Its evaluator is the contructor Fix. There is a unique morphism m from the initial algebra to any other algebra over the same functor. Let’s pick an algebra whose carrier is a and the evaluator is alg.

By the way, notice what m is: It’s an evaluator for the fixed point, an evaluator for the whole recursive expression tree. Let’s find a general way of implementing it.

Lambek’s theorem tells us that the constructor Fix is an isomorphism. We called its inverse unFix. We can therefore flip one arrow in this diagram to get:

Let’s write down the commutation condition for this diagram:

m = alg . fmap m . unFix

We can interpret this equation as a recursive definition of m. The recursion is bound to terminate for any finite tree created using the functor f. We can see that by noticing that fmap m operates underneath the top layer of the functor f. In other words, it works on the children of the original tree. The children are always one level shallower than the original tree.

Here’s what happens when we apply m to a tree constructed using Fix f. The action of unFix peels off the constructor, exposing the top level of the tree. We then apply m to all the children of the top node. This produces results of type a. Finally, we combine those results by applying the non-recursive evaluator alg. The key point is that our evaluator alg is a simple non-recursive function.

Since we can do this for any algebra alg, it makes sense to define a higher order function that takes the algebra as a parameter and gives us the function we called m. This higher order function is called a catamorphism:

cata :: Functor f => (f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a cata alg = alg . fmap (cata alg) . unFix

Let’s see an example of that. Take the functor that defines natural numbers:

data NatF a = ZeroF | SuccF a

Let’s pick (Int, Int) as the carrier type and define our algebra as:

fib :: NatF (Int, Int) -> (Int, Int) fib ZeroF = (1, 1) fib (SuccF (m, n)) = (n, m + n)

You can easily convince yourself that the catamorphism for this algebra, cata fib, calculates Fibonacci numbers.

In general, an algebra for NatF defines a recurrence relation: the value of the current element in terms of the previous element. A catamorphism then evaluates the n-th element of that sequence.

Folds

A list of e is the initial algebra of the following functor:

data ListF e a = NilF | ConsF e a

Indeed, replacing the variable a with the result of recursion, which we’ll call List e, we get:

data List e = Nil | Cons e (List e)

An algebra for a list functor picks a particular carrier type and defines a function that does pattern matching on the two constructors. Its value for NilF tells us how to evaluate an empty list, and its value for ConsF tells us how to combine the current element with the previously accumulated value.

For instance, here’s an algebra that can be used to calculate the length of a list (the carrier type is Int):

lenAlg :: ListF e Int -> Int lenAlg (ConsF e n) = n + 1 lenAlg NilF = 0

Indeed, the resulting catamorphism cata lenAlg calculates the length of a list. Notice that the evaluator is a combination of (1) a function that takes a list element and an accumulator and returns a new accumulator, and (2) a starting value, here zero. The type of the value and the type of the accumulator are given by the carrier type.

Compare this to the traditional Haskell definition:

length = foldr (\e n -> n + 1) 0

The two arguments to foldr are exactly the two components of the algebra.

Let’s try another example:

sumAlg :: ListF Double Double -> Double sumAlg (ConsF e s) = e + s sumAlg NilF = 0.0

Again, compare this with:

sum = foldr (\e s -> e + s) 0.0

As you can see, foldr is just a convenient specialization of a catamorphism to lists.

Coalgebras

As usual, we have a dual construction of an F-coagebra, where the direction of the morphism is reversed:

a -> F a

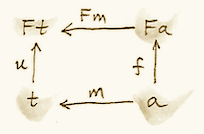

Coalgebras for a given functor also form a category, with homomorphisms preserving the coalgebraic structure. The terminal object (t, u) in that category is called the terminal (or final) coalgebra. For every other algebra (a, f) there is a unique homomorphism m that makes the following diagram commute:

A terminal colagebra is a fixed point of the functor, in the sense that the morphism u :: t -> F t is an isomorphism (Lambek’s theorem for coalgebras):

F t ≅ t

A terminal coalgebra is usually interpreted in programming as a recipe for generating (possibly infinite) data structures or transition systems.

Just like a catamorphism can be used to evaluate an initial algebra, an anamorphism can be used to coevaluate a terminal coalgebra:

ana :: Functor f => (a -> f a) -> a -> Fix f ana coalg = Fix . fmap (ana coalg) . coalg

A canonical example of a coalgebra is based on a functor whose fixed point is an infinite stream of elements of type e. This is the functor:

data StreamF e a = StreamF e a deriving Functor

and this is its fixed point:

data Stream e = Stream e (Stream e)

A coalgebra for StreamF e is a function that takes the seed of type a and produces a pair (StreamF is a fancy name for a pair) consisting of an element and the next seed.

You can easily generate simple examples of coalgebras that produce infinite sequences, like the list of squares, or reciprocals.

A more interesting example is a coalgebra that produces a list of primes. The trick is to use an infinite list as a carrier. Our starting seed will be the list [2..]. The next seed will be the tail of this list with all multiples of 2 removed. It’s a list of odd numbers starting with 3. In the next step, we’ll take the tail of this list and remove all multiples of 3, and so on. You might recognize the makings of the sieve of Eratosthenes. This coalgebra is implemented by the following function:

era :: [Int] -> StreamF Int [Int]

era (p : ns) = StreamF p (filter (notdiv p) ns)

where notdiv p n = n `mod` p /= 0

The anamorphism for this coalgebra generates the list of primes:

primes = ana era [2..]

A stream is an infinite list, so it should be possible to convert it to a Haskell list. To do that, we can use the same functor StreamF to form an algebra, and we can run a catamorphism over it. For instance, this is a catamorphism that converts a stream to a list:

toListC :: Fix (StreamF e) -> [e]

toListC = cata al

where al :: StreamF e [e] -> [e]

al (StreamF e a) = e : a

Here, the same fixed point is simultaneously an initial algebra and a terminal coalgebra for the same endofunctor. It’s not always like this, in an arbitrary category. In general, an endofunctor may have many (or no) fixed points. The initial algebra is the so called least fixed point, and the terminal coalgebra is the greatest fixed point. In Haskell, though, both are defined by the same formula, and they coincide.

The anamorphism for lists is called unfold. To create finite lists, the functor is modified to produce a Maybe pair:

unfoldr :: (b -> Maybe (a, b)) -> b -> [a]

The value of Nothing will terminate the generation of the list.

An interesting case of a coalgebra is related to lenses. A lens can be represented as a pair of a getter and a setter:

set :: a -> s -> a get :: a -> s

Here, a is usually some product data type with a field of type s. The getter retrieves the value of that field and the setter replaces this field with a new value. These two functions can be combined into one:

a -> (s, s -> a)

We can rewrite this function further as:

a -> Store s a

where we have defined a functor:

data Store s a = Store (s -> a) s

Notice that this is not a simple algebraic functor constructed from sums of products. It involves an exponential as.

A lens is a coalgebra for this functor with the carrier type a. We’ve seen before that Store s is also a comonad. It turns out that a well-behaved lens corresponds to a coalgebra that is compatible with the comonad structure. We’ll talk about this in the next section.

Challenges

- Implement the evaluation function for a ring of polynomials of one variable. You can represent a polynomial as a list of coefficients in front of powers of

x. For instance,4x2-1would be represented as (starting with the zero’th power)[-1, 0, 4]. - Generalize the previous construction to polynomials of many independent variables, like

x2y-3y3z. - Implement the algebra for the ring of 2×2 matrices.

- Define a coalgebra whose anamorphism produces a list of squares of natural numbers.

- Use

unfoldrto generate a list of the firstnprimes.

Next: Algebras for Monads.

August 28, 2017 at 5:44 am

I can’t figure out how to prove m ∘ j = id F i by stacking the two diagrams in the reverse order. Could you clarify it?

btw I found another proof:

j ∘ m = id i => Fj ∘ Fm = id F i (by functor law)

so Fj ∘ Fm = m ∘ j = id F i (by the first commuting diagram )

August 28, 2017 at 4:32 pm

Actually, your proof is better (that’s also how it’s done in nCatLab). I will edit the post. Thanks for spotting it.

From the stacking you can get m∘j∘Fj = Fj, and you can get rid of Fj by composing it (on the right) with Fm.

August 28, 2017 at 6:50 pm

Ah, thanks. I should have thought of that…

November 16, 2017 at 2:04 pm

I understand the proof as: if there exists an initial object in the category of algebras over the endofunctor F, then it must be the least fixed point of F.

My question is: how do we go from there to stating that taking the fixed point of any endofunctor F gives us an initial object for the category of F-algebras? How do we know that an initial algebra actually exists over F?

We derive the Haskell code of a catamorphism from the fact that the diagram commutes, which as far as I understand, derives from the fact that Fix is our initial algebra. I might be missing something important, but I couldn’t find the proof of it.

November 16, 2017 at 3:06 pm

My traditional copout is that the proof would fall outside of the scope of this book. If the proof were simple and intuitive, I’d write about it. But here’s the general idea: You start with an initial object and apply powers of F to it, forming a chain. The colimit of this chain gives you the initial algebra. The proof is due to Adámek.

November 16, 2017 at 3:51 pm

Thanks!

I was confronted to Adámek’s theorem when browsing nCatLab on this topic but I was not sure it was actually the missing link in my reasoning.

December 31, 2017 at 12:37 am

[…] following this blog about F-algebras It explains […]

January 11, 2018 at 2:58 am

Thanks again for this wonderful series.

I have a question about terminology. In the section on catamorphisms you say, referring to the function cata, that “Since we can do this for any algebra alg, it makes sense to define a higher order function that takes the algebra as a parameter and gives us the function we called m. This higher order function is called a catamorphism”.

However, you also state that “the catamorphism for this algebra, cata fib, calculates Fibonacci numbers” and later that “the resulting catamorphism cata lenAlg calculates”. In these cases the word catamorphism is used to denote (some instance of) m itself. It is my understanding that this latter use is in fact more consistent with the category theory, which states that there is a unique morphism m from the initial algebra to any other algebra over the same functor, and this m is what we call the catamorphism.

Also: following the latter definition, the question whether some function in Haskell is a catamorphism is independent of its implementation (whether using the generic function or not). If the function can be refactored into an application of the generic function cata it is a catamorphism.

Am I rightly confused? Can you help me become un-confused?

January 11, 2018 at 8:41 am

You’re right. It’s the case of naming a function after what it’s producing.

August 6, 2018 at 9:34 am

I get stuck with this silly problem: If there is a category of F-algebras where every object in the F-algebra is a pair of an object a of the original category and morphism from F(a) → a. So take for example the functor F(X) = 1+ Char × X . The gives as the initial algebra the list of chars or strings. We can also get F(Int) = 1+ Char×Int which we can use to count the length of a list. But if I take F⚬F(X) to be a list of list of chars, then I translate this as F(F(X)) = 1 + Char × F(X) which would be a char followed by a list of chars… but that’s not what we usually mean by a list of lists… What am I getting wrong here?

August 6, 2018 at 10:34 am

Notice that a list of As is defined as the initial algebra of the functor FA X = 1 + A × X. If you want to define a list of lists, you have to replace A, not X, with a list.

August 6, 2018 at 12:29 pm

Yes, I suppose my problem came from reading the next article on Algebras of Monads, where you mention the μ operator which I keep associating with flattening. So I think I kept making two errors.

1) I kept thinking of F⚬F as Lists of Lists for the functor F(X)=1+ Char×X

2) because I thought of μ as flattening I thought of F⚬F as lists of lists

Asking the question has helped clarify it, as it often does. In Ralf Hinze’s difficult but very helpful article “Generic Programming with Adjunctions” [1] he

introduces the μ Functor of type 𝒞^𝒞 → 𝒞 which takes an endo functor in 𝒞 to its initial algebra. So for F above μF = Strings . And F(μF) is just another string as it adds a charater to the front of it.

The Arrows in the higher order μ Functor maps natural transformations between functors F and G to an arrow μF to μG. If G(X)=1+μF×X then I guess the arrow would be the unit. Interestingly μG would then be a list of strings (as you point out).

So I suppose my question was as we think of Monad Algebras as algebras and we think of lists as monads and algebras, but we have to change algebra to get a list of list, when do those appear in a particular algebra? Is it that the above F(X) and G(X) are not monads but that something more monoidal like

M(X)=1+X×X is?

[1] https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-32202-0_2

PS. I don’t seem to be able to edit (or delete) posts I make here, so I hope I have not made too many mistakes in this post

August 6, 2018 at 1:46 pm

You have to carefully distinguish between various structures. There is a family of endofunctors FA X parameterized by A. Then there is a category of algebras for each of these endofunctors. In that category there is an initial algebra, that’s the list of As.

This initial algebra is also an endofunctor in A. This particular endofunctor happens to be a monad, giving you the list monad. There is also a category of algebras for this endofunctor. Finally, there is a subcategory of these algebras that are compatible with the monad. This category is isomorphic to the category of monoids.

February 28, 2019 at 11:51 am

Tiny correction I think:

‘As usual, we have a dual construction of an F-coagebra’

should be:

‘As usual, we have a dual construction of an F-algebra’

February 28, 2019 at 2:59 pm

F-coalgebra is dual to F-algebra.

May 9, 2019 at 10:54 am

As an exercise I’m writing a lambda calculus interpreter in Haskell and I am modeling the language using F-Algebras (this if my first attempt at writing a compiler of any type). Below is the data type for my lambda expressions:

“

data LambdaF a = LVar String | Bind String a | App a atype Lambda = Fix LambdaF

“

To perform alpha substitution I wrote another data type and both a catamorphism and anamorphism (and thus a hylomorphism):

“`

data Alpha a =

NoAlpha Lambda

| VarAlpha Lambda

| BindAlpha VarName a

| AppAlpha a a

deriving Functor

mkAlpha :: VarName -> Lambda -> CoAlg Alpha Lambda

mkAlpha v n = mS . unFix

where

mS x@(LVar s)

| v == s = VarAlpha n

| otherwise = NoAlpha (Fix x)

mS x@(Bind s e)

| v == s = NoAlpha (Fix x)

| otherwise = BindAlpha s e

mS (App e1 e2) = AppAlpha e1 e2

reAlpha :: Alg Alpha Lambda

reAlpha (NoAlpha l) = l

reAlpha (VarAlpha l) = l

reAlpha (BindAlpha s l) = Fix $ Bind s l

reAlpha (AppAlpha e1 e2) = Fix $ App e1 e2

alpha v n = hylo reAlpha (mkAlpha v n)

“`

My question is three fold:

Is there a more succinct way of writing this?

It seems that there is a one-to-one correspondence between algebras and recursive functions. Is it a better idea to stick with writing recursive functions for simple tasks and use F-Algebras for more complicated tasks (as in your blog “Stalking a Hylomorphism in the Wild”)

After writing the above code I’ve noticed that Alpha looks very similar to LambdaF and therefore It seems like I could make an alpha substitution constructor as part of the LambdaF type namely:

LambdaF a = … | Sub String a awhere String is the variable to perform the substitution on and the first

ais the lambda expression to substitute and the secondais the lambda expression to perform the substitution on. The issue I’m running into how to write the Algebra for this. Is adding theSubconstructor toLambdaFjust a bad idea? Thanks! (And Category Theory For Programmers has been a great read btw!)November 17, 2019 at 11:39 am

[…] from Bartosz Milewski’s blog, is great. A post related to some of the current topic is this one on F-algebras. Returning, though, to the code at […]

January 25, 2020 at 9:20 am

catahaving no boundary condition really hurts my brain..March 29, 2020 at 7:56 am

There is a typo,

data Stream e = Stream e (Stream e)

should be

data Stream e = StreamF e (Stream e)

March 29, 2020 at 8:21 am

It might be a bit confusing, but it’s correct. The first

Streamis a type constructor, the second is the data constructor, the third is the use of type constructor.The version with

StreamFwouldn’t compile asdatasinceStreamFhas been defined earlier (it would astypethough)August 17, 2020 at 4:22 am

Hi Bartosz. I’m wondering if this implementation for catamorphisms etc. applies to languages besides Haskell, say Idris?

You said “Back to Haskell: We recognize i as our Fix f, j as our constructor Fix…”.

But Fix f is just the type of fixed point of f (not necessarily the least fixed point).

Now I think I heard in Haskell fixed points are unique, so we can indeed identify Fix f with the initial algebra.

But in Idris I think it’s not true: the initial algebra and final coalgebra might not be the same (e.g. the types of finite lists and of possibly infinite lists are different, both being fixed points of x |-> 1 + a * x.)

So how can we implement this in Idris?

August 17, 2020 at 8:05 am

Good question. I wrote a separate series of posts addressing this. They are the same in Haskell because (unlike Idris) it’s a lazy language. https://bartoszmilewski.com/2020/04/22/terminal-coalgebra-as-directed-limit/

June 10, 2021 at 12:18 am

Hi and thanks for the amazing post. I started learning Haskell last week, so I might say a lot of incorrect things, but I think one might say the following:

It is clear that if you take Stream A : Set -> Set to be the endofunctor that associates to Y |–> A x Y, then the initial and terminal algebra are radically different. Anyhow, in Haskell things are a bit different: from what I understand from your post regarding coalgebras https://bartoszmilewski.com/2020/04/22/terminal-coalgebra-as-directed-limit/ it looks like Void is actually non empty and the terminal and the final coalgebra “agree”. So Haskel is different from set,

But what if we say that Haskell is like the category of POINTED Sets without the empty set (which I denote Set)? Morphisms in this category are functions preserving the fixed point, so in particular the final and the initial objects are the same thing, namely (,), the set with only one object and the fixed point given by that unique object.

We can then consider the endofunctor Stream (A,a) : Set-> Set* sending (Y,y) to (A x Y, a x y).

An initial algebra for this functor is given by the set of Finite lists, which I will denote with “FinList”. The terminal coalgebra is just given by the set of possibly infinite lists, which I will denote with “List”.

Notice that also in this case we have that FinList and List are not isomorphic, but we have a little advantage:

In particular we have the usual algebra morphism FinList->List, but also a (canonical) morphism of pointed sets List->FinList sending all infinite lists to the empty list!

So it looks like:

– Anamorphisms are computed correctly and are given by the universal property of coalgebras.

-“Catamorphisms” are the composition of the function List->FinList with the actual catamorphism (given by the universal property of the initial algebra FinList). So they are still unique in this sense.

So in particular Fix is not initial and terminal, but it happens to be “universal enough”.

If this is roughly correct it would get rid the issue I have considering Fix both as an initial algebra and a final coalgebra. Am I totally off? Is this analogy ok?

June 10, 2021 at 11:06 am

You might be interested in reading this discussion: http://math.andrej.com/2016/08/06/hask-is-not-a-category/